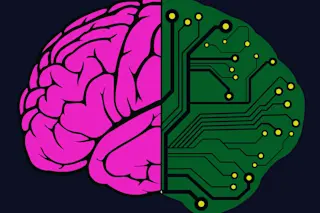

The nose of an F-22 jet fighter in a computerized flight simulator tips up, then down. The maneuver seems routine, even rudimentary. But in this case the aircraft is piloted by 25,000 rat neurons in a tiny dish, hooked to an electrode array hardly bigger than the head of a pin.

The experiment in Thomas DeMarse’s biomedical engineering lab at the University of Florida is a breakthrough in efforts to understand—and someday duplicate—how a living brain processes information.

The neural cells, plated onto an array of 60 electrodes attached to a computer, are nourished in a small dish until they grow connections between one another. They then receive electrical pulses from the virtual F-22 that are timed to correspond to the angle of the plane’s nose as it points above or below the horizon. “The timing determines how much of an effect you have on the conductivity within the network, ...