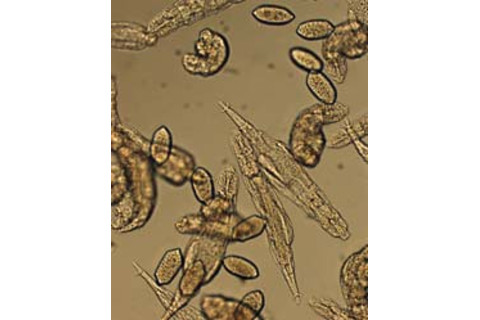

You inherited your genes from your parents, half from your father and half from your mother. Almost all other animals contend with the same hand-me-down processes, but not the bdelloid rotifers. This intriguing group of small freshwater creatures are not content with their genetic hand-me-downs; they import genes too. A new study shows that their genomes are rife with legions of foreign DNA, transferred from bacteria, fungi and even plants.

The swapping of genetic material is all part of a day's activity for bacteria but it's incredibly rare in animals. But bdelloids are bringing in external genes to an extent that's completely unheard of in complex organisms. Each rotifer is a genetic mosaic, whose DNA spans almost all the major kingdoms of life.

Bdelloid rotifers are no strangers to attention-grabbing science. They are one of the only groups of animals to have completely abandoned sex. No male bdelloid has ever been found and for 80 million years, the females have been reproducing solely through cloning themselves. They are great survivors; at any point during their lives, they can be completely dried out and return from dormancy after being rehydrated. And as I've explained before, they are most radiation-resistant animals on the planet, and can tolerate doses a hundred times more than what would kill a human.

Genetic mosaic

This radiation tolerance was discovered by Eugene Gladyshev and colleagues from Harvard University, who now return with yet another discovery that sets bdelloids apart from other animals. This time, it was made almost by accident. Gladyshev initially set out to study a group of DNA sequences called transposons, that have the ability to jump around genomes.

But among the DNA of the bdelloid Adineta vaga, he unexpectedly found traces of bacterial, fungal and even plant genes, many of which are incredibly rare. About half have no counterparts in animals and one gene is found in only 10 species of bacteria. Some genes appear to have been smuggled into the rotifer genome as a set, for they appear in the same order and orientation that they do in fungi or bacteria.

The genes are not passive hitchhikers either. Many appear to be fully functional; in their native species, they are involved in breaking down sugars and carbohydrates, or producing useful molecules like antibiotics and toxins. The chances are that the rotifers are putting them to similar uses.

The recruitment process is also an ongoing one. Some of the foreign genes were clearly brought in so long ago that they have picked up characteristics that are similar to the rotifer's own genes. Others, which are relatively unchanged from their counterparts in bacteria or fungi, are probably more recent additions.

The imported genes are found at the end of the rotifer's chromosomes. They are concentrated around structures called telomeres, that cap the ends of DNA strands like the plastic tips of shoelaces. In contrast, the central, gene-heavy parts of each chromosome are almost totally devoid of foreign genes.

Sex, schmex

It's not clear why the bdelloids are so good at incorporating new genes, but their lifestyle may hold the answer. The freshwater ponds they call home frequently dry out and they cope with this by entering into a dry, dormant and extremely tough state. This drying process breaks their cell membranes and shatters their DNA. The bdelloids are very good at repairing these injuries, but it provides a temporary entrypoint for chunks of foreign DNA from species in the surrounding environment that have also succumbed to similar damage.

This newly discovered ability may help to explain the success of the bdelloids despite their rejection of sex. Compared to sex, asexual reproduction is often seen as a poor long-term strategy, for it lacks the chromosomal shuffling that brings about genetic diversity and is thought to gives species an adaptive edge in the face of new challenges. But bdelloids have contradicted this theory by being very successful; there are over 360 species alive today.

Gladyshev suggests that this success may be due to their ability to pick up new genes from their environment. If the main advantage of sex is that it promotes genetic diversity, why worry about it when you have the gene pools of entire kingdoms available to you?

Reference: Gladyshev, E.A., Meselson, M., Arkhipova, I.R. (2008). Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers. Science, 320(5880), 1210-1213. DOI: 10.1126/science.1156407

Images by Eugene Gladyshev and Diego Fontaneto