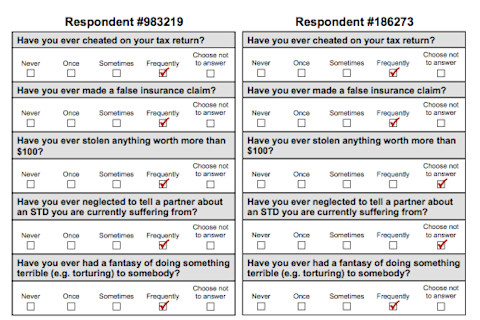

You're creating a profile for an online dating site when you come to a question you're not sure you want to answer—say, "Do you smoke?" You might be more comfortable leaving it blank than sharing the truth with all your potential dates. But a series of experiments says that we tend to judge people harshly when they withhold personal information. Even someone who shares an unpleasant truth is more appealing, trustworthy, and hirable than someone who'd rather not say. Harvard Business School professor Leslie John and her colleagues designed the study to find out whether nondisclosure has costs. When people comfortably share so many personal details on social media, are non-sharers deemed less trustworthy? (Being Bostonians, the authors cite Tom Brady as an example—specifically, certain "insinuations" about the quarterback when he refused to hand over his email and phone records during last year's Deflategate scandal.) The first experiment looked at dating. Subjects read two questionnaires, supposedly filled out by potential dates. The questionnaires asked how often they engaged in five sketchy behaviors, including stealing, insurance fraud, and neglecting to tell partners about STDs. On a scale from "Never" to "Frequently," one of the potential dates had answered all five questions the same way. The other potential date had answered three of the questions the same as the first person, but checked off "Choose not to answer" for the other two. The verdict? No matter how often the first potential date (the "revealer") admitted to doing these things, subjects preferred that person to the one who left some questions unanswered (the "hider"). Overall, almost 80% wanted to date the revealer. This preference held up even when the revealer admitted to frequently stealing expensive items and, um, fantasizing about torturing people.

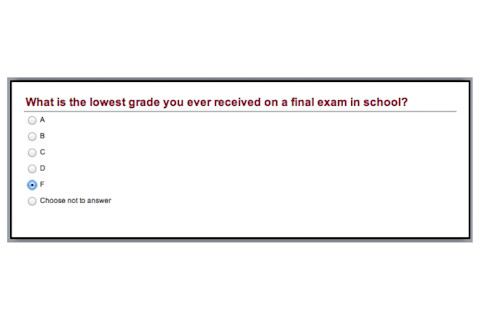

Sixty-four percent of subjects would rather date the person on the left. In a similar experiment, potential dates had answered questions about positive behaviors like donating blood or giving to charity. Some had chosen not to answer, as before. Still others had their answers omitted by a computer glitch or website issue. Even though the actions in this questionnaire were positive, subjects still didn't like subjects who with missing answers. People felt somewhat warmer toward dates whose answers were left off because of an error—but they still preferred dates who revealed everything. Next, the researchers wanted to know whether people who withhold personal information seem less trustworthy. They paired up subjects to play a trust game. The first subject would get $5 and could choose to send some portion to the second subject. Then that money would be tripled, and the second subject would decide how much of it to send back. Before the experiment, the first subjects saw a set of personal questions their partners had filled out. In some cases, the partners had marked "choose not to answer." As predicted, subjects sent significantly less money to partners who seemed to be hiding something. What if someone isn't dating or playing a silly economics game, but applying for a job? The researchers asked subjects to imagine they were an employer considering two job applicants. A question on the application was "What is the lowest grade you ever received on a final exam in school?" One candidate had admitted to getting an F; the other had chosen not to answer.

Eighty-nine percent of subjects would rather hire this person for a job than someone who selects "Choose not to answer." Even though the hider candidate literally could not have done any worse than the one with an F, nearly all the subjects chose to hire the revealer instead. They said that they considered this applicant more trustworthy. In a similar experiment, one group of subjects imagined they were applying for a job and answering a question about drug use. Seventy percent of them thought it was better not to answer the question than to admit they'd used drugs. But when another group of subjects acted as the employer, they said they'd rather hire the candidate who admitted to using drugs than the one who didn't answer the question. As much as we mock oversharers, then, it seems we feel more trusting toward people who spill personal details. In that online dating profile, admitting to being a smoker might be more appealing to potential dates than covering it up. And the people behind Match.com seem to already know this. If someone refuses to answer a question, it appears on his or her profile with a cheerful "I'll tell you later!"

Image: by Steve Ellmore (via Flickr)

John, L., Barasz, K., & Norton, M. (2016). Hiding personal information reveals the worst Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1516868113