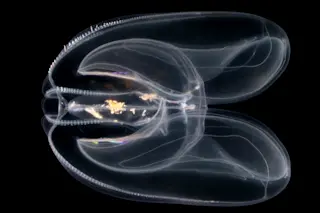

Few things on Earth are spookier than viruses. The very name virus,from the Latin word for "poisonous slime," speaks to our lowly regard for them. Their anatomy is equally dubious: loose, tiny envelopes of molecules—protein-coated DNA or RNA—that inhabit some netherworld between life and non-life. Viruses do not have cell membranes, as bacteria do; they are not even cells. They seem most lifelike only when they invade and co-opt the machinery of living cells in order to make more of themselves, often killing their hosts in the process. Their efficiency at doing so ranks them among the most fearsome killers:Ebola virus, HIV, smallpox, flu. Yet they go untouched by antibiotics, having nothing really biotic about them.

Bernard La Scola peers into an electron microscope in his laboratory in Marseille, France. | Jörg Brockmann

The existence of viruses was first surmised just over a century ago by Dutch botanist Martinus Beijerinck. ...