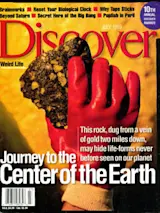

Braving100-degree temperatures two miles down in South Africa’s East Driefonteingold mine, geologist T. C. Onstott sheds his shirt to collect microbe sampleswith biologist Duane Moser. Scientists once thought life could not be sustainedso far underground, but Onstott says evidence now suggests “microbes have beenhere for 2 billion years.”

Four scientists wearing coveralls and hard hats shuffle warily into asteel cage the size of a closet, cramming themselves against a dozenminers. The doors clang shut, and the bottom seems to drop out as theelevator plunges hundreds of stories down into the darkness--No. 5Shaft in South Africa's East Driefontein gold mine. Within moments theair becomes oppressive--hot and curiously thick. This is one of thedeepest excavations in the world, burrowing more than two miles towardthe center of Earth. At the bottom of the mine, radioactivity and heatfrom the planet's core raise the temperature of the stone in thetunnels to a searing 120 degrees ...