In the mid-’80s, scientists discovered a giant fungus growing in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Now, researchers have found the organism is at least 2,500 years old. And the secret to the mushroom’s longevity might be a genome that’s highly resistant to mutation, the team reports today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The discovery could help researchers figure out why cancer genomes are so unstable.

Forest Recycler

In 1983, Johann Bruhn planted red pines in the forest. Within the next few years, the trees began to die. The trend continued for about 15 years. Bruhn, a forest health specialist at the University of Missouri in Columbia, traced the trees’ deaths to a species of honey mushroom dubbed Armillaria gallica, a parasitic fungus that preys on trees weakened by drought, insects and other fungal infections. Bruhn examined the fungus, taking it out of the forest to find out whether a unique clone was responsible for the deaths. That’s when he stumbled on something unexpected.

“It looked like one of these clones … extended off into the forest,” Bruhn said. “We didn’t know how far.”

So he and a team of researchers collected more fungus samples further and further afield. By 1992, the researchers knew the fungus was big. They estimated its mass (about 11 tons) and age (at least 1,500 years-old) and reported their findings in a scientific journal.

But the team hadn’t reached the edge of what became known as the “humongous fungus.” That only happened in the last few years. Now, Bruhn and colleagues estimate the fungus is about 1,000 years older and four times bigger than they previously thought.

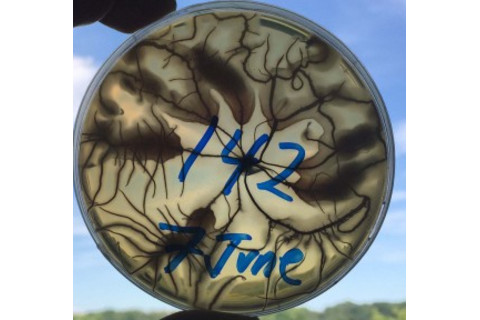

An isolated sample of the "humungous fungus" clone. (Credit: Johann Bruhn)

Johann Bruhn

An isolated sample of the “humungous fungus” clone. (Credit: Johann Bruhn)

Cancer Contrast

The discovery begged the question: How did it survive for so long and get so big? The researchers suspected that the fungus must be incredibly stable genetically. So the team sequenced the organism’s genome from collected samples.

“It turned out that this fungus, this clone of Armillaria gallica, has an extremely low rate of mutation,” Bruhn said. The find is especially surprising given the fungus is so large. Bruhn and colleagues estimate it spreads through nearly 190 acres of the forest floor.

The individual mushrooms themselves last just a few weeks, but the clone itself, as identified by its genetic code, persists. Bruhn compares it to a redwood tree, where the most ancient wood cells are long-dead. “The defining feature of an individual is its unique genetic code that defines the rule set for its continued existence,” he said. “In this sense, the cell lineage of the humungous fungus dates back to a single sexual mating event roughly 2,500 years ago that defines its way of life.”

And, perhaps most intriguingly, the stability of the mushroom’s genome stands in stark to contrast to cancers, which have radically unstable genetic material.

“Our A. gallica must be at the opposite extreme as cancer,” Bruhn said. The fungus’ mutation rate is “a counterpoint to cancer mutation.”

“It could be an interesting point of comparison,” James Anderson, a population geneticist who co-led the new work with Bruhn, said in a statement. “Cancer is so unstable, mutates at a high rate and is prone to genomic changes, while A. gallica is a very persistent organism with few mutations.”