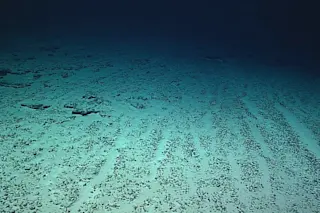

On the seafloor, “marine snow” is constantly falling. Bits of dead plankton, decaying fecal material, biological remnants from shore – it all finds its way to the bottom of the ocean, delivering needed sources of organic molecules and energy to the microbial communities lying in wait.

Over time, this snow – along with sediment mineral grains – accumulates, burying previous layers. In Denmark’s Aarhus Bay, for example, digging ten meters down beneath the seafloor is like going 8,700 years back in time. The ability to see so much time in so compressed a space is a boon to evolutionary biologists, since it allows them to track genetic changes and community shifts in a relatively static environment. With no evidence of fluid flow or bioturbation to move microbes around or facilitate horizontal gene transfer, you’re stuck with the neighbors you’ve got at the surface – only evolutionary selection or death can ...