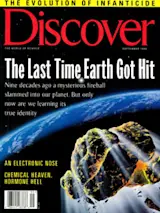

On June 30, 1908, a vast fireball raced through the dawn sky over Siberia, then exploded with the force of 1,000 Hiroshima bombs. The heat incinerated herds of reindeer and charred tens of thousands of evergreens across hundreds of square miles. For days, and for thousands of miles around, the sky remained bright with an eerie orange glow--as far away as western Europe people were able to read newspapers at night without a lamp. The effect was much like that of a great volcanic eruption, yet there had been no eruption. The only objective indication of the extraordinary event was a quiver on seismographs in the Siberian city of Irkutsk, indicating a moderate quake some 1,000 miles north in a remote region called Tunguska.

Scientists did not come to Tunguska for another 19 years, apparently reluctant to travel to a site so swampy and remote. When they did finally come, ...