Sea snakes have some of the most potent venoms of any snake, but most of the 60 or so species are docile, rare, or sparing with their venom. The beaked sea snake (Enhydrina schistosa) is an exception. It lives throughout Asia and Australasia, has a reputation for being aggressive, and swims in estuaries and lagoons where it often gets entangled in fishing nets. Unwary fishermen get injected with venom that’s more potent than a cobra’s or a rattlesnake’s. It’s perhaps unsurprising that this one species accounts for the vast majority of injuries and deaths from sea snake bites.

But this deadliest of sea snakes has a secret: it’s actually two sea snakes.

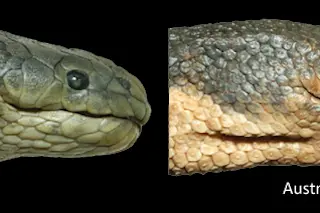

By analysing the beaked sea snake’s genes, Kanishka Ukuwela from the University of Adelaide has shown that the Asian individuals belong to a completely different branch of the sea snake family tree than the Australian ones. They are ...