The Earth's crust has a dual personality. On one hand, there are the continents. Many times, the crust that makes up the continents can be very old, upwards of 3 to 4 billion years old! Yet, the oceanic crust that makes up a majority of the planet's surface doesn't get anywhere near as well. In fact, the oldest oceanic crust is only about 220 million years ago, or ~5% of the age of the Earth. We know we've had oceans and oceanic crust for billions of years, so where has it all gone?

That's where subduction comes in. Subduction is the process where pieces of the Earth's crust get literally shoved back into the next layer down (the mantle). The mantle isn't a rigid solid but rather a plastic solid, so it can deform as the crust gets pushed into it. It also isn't as dense as old crust, so that crust will "sink" through the mantle, maybe ending up at the boundary between the mantle and core thousands of miles below our feet.

Basic model of a subduction zone, showing how the oceanic crust is shoved underneath the continental crust. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Wikimedia Commons.

Yet, all crust isn't the same. Continental crust is usually 20-40 miles (30-70 kilometers) thick and is made of relatively low density rock like granite. Oceanic crust is closer to 4-6 miles (7-10 kilometers) thick and made of denser rock like basalt. This means that when these two types of plates collide as they move on the planet's surface, oceanic crust doesn't stand a chance. It gets shoved underneath the continental crust and back down into the mantle.

Over the history of plate tectonics on Earth, a vast amount of oceanic crust has been recycled back into the mantle through subduction while the continents have been able to (mostly) resist this because of their thickness and buoyancy. Like a Humvee in a demolition derby of Fiats, the continents won't go down.

Subduction allows for tectonics to work because if oceanic crust didn't subduct, we'd either need an expanding Earth (which isn't happening) or we'd have thick layers of dense rock as the oceanic crust crumpled that would have led to the end of plate tectonics long before now.

The Atlantic Ocean was born ~150 million years ago when North and South America split from Africa and Europe. This process continues today with a mid-ocean ridge running down the middle of the ocean, moving the current plates further apart. We see the volcanism caused by this in places like Iceland. Yet, no ocean is forever. The Atlantic Ocean will eventually begin to close as we head towards the next supercontinent.

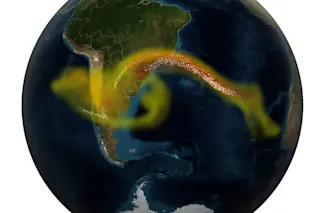

A map showing the location of this study and the two current subduction zones in the Atlantic Ocean (Lesser Antilles and Scotia Arcs). Credit: AGI.

AGI.

However, exactly how the ocean basin will begin to close is still a mystery. You need subduction and there is currently very little of that in the Atlantic Ocean. The Lesser Antilles Arc and the Scotia Arc (in the southern Atlantic) are both small subduction zones that potentially migrated from the Pacific Ocean into the Atlantic basin. They're both on the west side of the ocean and it is hard to imagine that they alone will be responsible for the end of the Atlantic.

New research published in Geology from João Duarte and his colleagues suggests that we may already have a subduction zone invading the Atlantic Ocean from the east. Namely, it might be coming from the straits of Gibraltar out of the Mediterranean Sea.

Duarte and his colleagues point to a trench located with the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea as evidence that a slice of Atlantic Ocean crust is being thrust into the mantle to the east of the Straits of Gibraltar. They have combined geophysical data and geologic age data from the Mediterranean basin to create a model that shows that this Gibraltar Arc may be moving quite slowly into the Atlantic Ocean today, but unlike what other workers have postulated, it is not "dead".

A model showing the location of the Atlantic Gibraltar arc in 80 million years. Credit: Duarte and others (2024), Geology.

Duarte and others (2024

Instead, Duarte and others say that the migration of the arc has merely stalled and their models suggest that it will speed back up again, sending a new subduction zone into the Atlantic basin in the future (being tens of millions of years from now). This subduction zone will then start sending oceanic crust to its mantle-y grave (and sprout a line of volcanoes off the coast of Morocco and Portugal).

The combined impact of the "infection" of the current Atlantic Basin by these subduction zones off Gibraltar, in the Caribbean area and south of South America will spell doom for the Atlantic Ocean. It might take another 200 million years to do it, but the eastern and western hemispheres will collide (again), likely producing a long mountain belt from Scandinavia to Patagonia. When that new supercontinent is born, the Atlantic will be finished but, as Semisonic put it "every new beginning comes from some other beginning's end."