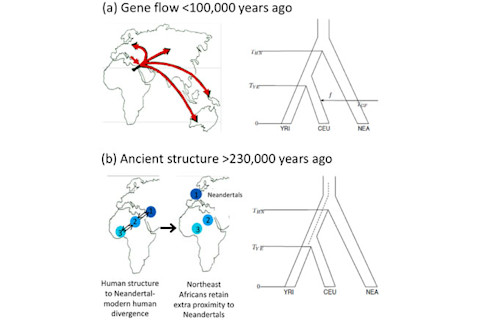

I have mentioned the PLoS Genetics paper, The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans, before because a version of it was put up on arXiv. The final paper has a few additions. For example, it mentions the generally panned (at least in the circles I run in) PNAS paper which suggested that ancient population structure could produce the same patterns which were earlier used to infer admixture with Neandertals (the authors also point to Yang et al. as a support for the proposition of admixture rather than structure). The primary result, dating the admixture between Neandertals and anatomically modern humans ~40-80,000 years before the present, is reiterated. An interesting aspect is that their method is to utilize linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay. It's interesting because tens of thousands of years is a hell of a long time to be able to detect an admixture event via LD! In particular because there's likely a palimpsest effect where there are intervening admixtures and other assorted demographic events (e.g., bottlenecks and selective sweeps can also generate LD). So how'd they do it? Basically the authors figured out a way to ascertain which pairs of SNPs may have introgressed from Neandertals by comparing the frequency in modern humans to Neandertals at those given SNPs (in particular, by looking at variants at low frequency in Africans and derived in Neandertals). A major technical problem here is the "genetic map" which allows one to assess what the nature of recombination over time is going to be which breaks apart the associations which are the hallmark of LD is not particular precise enough to robustly allow them to make the inferences that they want. The methods which they used to correct for these problems are ingenious and clever, and as is usually the case with this group the supporting information is well worth the read if you are a geneticist. But I am of a mind to recall what Dr. Joseph Pickrell's statement about the nature of peer review in such specialized and fankly arcane field implied: that the number of genuine peers is relatively small. Unlike physicists or economists most biologists are not formally trained in a common technical mathematical language. This explains the surplus of people from physics and mathematics backgrounds in many genomic laboratories. These are people who can parse and analyze big data, and extract signal from the noise by generating their own statistical tools as needed. But despite the forbidding formal aspect to the methods, the results coming out of these laboratories are still of interest, both academically (scientists are interested in stuff, period) and professionally (scientists like to use the methods that others develop) to those outside the discipline. And yet I believe that a divergence is developing here, as the methods developers are blazing to cut deep into the swell of data are moving well ahead of where other biologists can follow. Of course it is not just biologists. These particular specific questions about deep history and the human phylogenetic tree is of great interest to paleoanthroplogists, most of whom clearly can not follow with any fluency the debates about ancient structure or admixture, and the relevant of D-statistics. This is clearly what happened when Richard Klein convinced The New York Times to write an article which brought to light his professional gripes with the statistical geneticists who have upturned his nicely situated apple-cart, and offered up a compelling competitor to him in his domain specific specialty. But in Klein's defense his elegant verbal models were at least clear to the general public. There is a methodological opacity to statistical genomics which we have to admit is undeniable. Ultimately from my own personal experience there is one primary way to truly grokk what is going on in a paper like this:

replicate their analyses with the same computational techniques, and develop one's own intuition

. Unfortunately this takes time, and everyone has their own tasks before them, so less of this happens than should be the case (e.g., thousands of simulations are not cheap computationally). But all groups like the one above can do is provide the software tools, and point to where the data is (this emphasizes the crucial importance of open science today). Others can reanalyze, and importantly replicate simulations and modulate parameters to their own liking. This is all much more useful than armchair critiques, peer or not. Magic becomes a skill once you become familiar with it. Citation: Sankararaman S, Patterson N, Li H, Pääbo S, Reich D (2012) The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans. PLoS Genet 8(10): e1002947. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002947