Sea urchins may not have brains, but they’ve managed to outsmart the scientists studying them by growing their sharp spines in ways that seem to defy the laws of nature. Recently, a team of researchers at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science figured out how they do it. The secret: a beautiful and elegant form of crystal engineering.

Sea urchins use spines for protection from predators and for locomotion. Unlike typical crystal structures like shells, which incorporate thousands of smaller, geometrically symmetrical crystals attached to each other, each spine on a sea urchin is a single large calcite crystal with its own convoluted shape. “These spines are elaborate, and they have no flat surfaces,” says structural biologist Steve Weiner. “Despite that, all the atoms are aligned from one end of the spine to the other, which makes them single crystals. And they can be several centimeters long. This is extraordinary.”

More extraordinary is how urchins go about regenerating spines that have broken off. First, they produce a gel-like material that is densely packed with calcium carbonate molecules. Then they wait—sometimes for days—until the molecules line up perfectly so that they form a single elaborately shaped crystal. “That’s the trick the sea urchin developed,” says chemist Lia Addadi, Weiner’s research partner. “They lay down the material, and only when it’s in place do they allow it to crystallize.”

The sea urchin’s methods are a little like making glass underwater. “You’re dealing here with something like a very sophisticated ceramic organized into extraordinary shapes,” Weiner says. “It was not prepared in an oven at high temperatures but grown at ambient temperatures and pressures.” Engineers are certain to take notice. “There might be applications, for instance, in micro-optics, in electronics,” Weiner says. “Once the process has been identified, you can use the same principle to develop synthetic materials.”

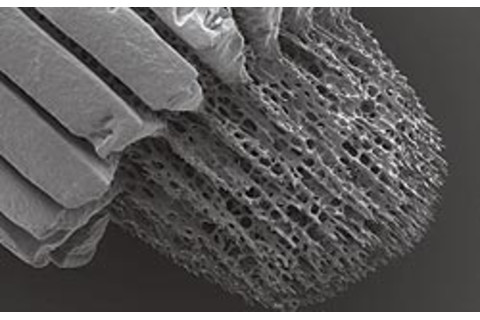

Sea urchins have seemingly countless spines each made from a single calcite crystal. The tiny creatures begin regenerating these spines whenever one or more breaks off. A series of electron micrographs taken at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, shows the process.

The initial step is a precursor, during which the urchins produce amorphous calcium carbonate. The material is called amorphous because it has no fixed form and has not crystallized. Even as the carbonate starts to aggregate at the ends of broken-off spine shafts, crystallization is forestalled.

By the fifth day, the crystal has started to grow out of the broken shaft.

Within seven days, it shows signs of being significantly formed in most cases. However, the entire process of spine regeneration can take as long as two weeks. “The crystal is then stable and hard,” says Weizmann researcher Lia Addadi, a chemist. “It presumably has properties that are advantageous for the sea urchin, and the shape has been imprinted.”

All images courtesy of the Weizmann Institute of Science.