When a volcano erupts, it can spew a cloud of ash miles into the stratosphere. It makes for an impressive sight, and an even more impressive amount of sheer material — large eruptions can loft cubic miles of rock and ash skyward.

And, to add to the wow factor, the clouds sometimes spawn their own lightning. As the cloud swirls chaotically in its journey skyward, the jagged ash particles are rubbed against one another, causing static electricity to accumulate. Static electricity in nature is released in the form of lightning, and volcanic ash clouds have been recorded releasing salvos of lightning bolts. It’s often called dirty lightning, and it makes for quite a spectacle.

Ka-Boom

Where there’s lightning, we expect to hear thunder. But researchers had never before caught volcanic thunder on tape before, in part because the noise of the eruption often drowned it out. Some questioned the existence of volcano thunder.

Now, researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey say they have finally captured a recording of the elusive phenomenon, during the 2017 eruption of Bogoslof in Alaska. They published their findings Tuesday in Geophysical Research Letters.

The volcano sits off the mainland and forms part of the volcanically active Aleutian island chain. Beginning in December of 2016, Bogoslof experienced the first in a series of eruptions that continued well into the summer of 2017, eventually more than quadrupling the size of the island. The ash clouds grew so large that aviation in the region was temporarily disrupted.

Scientists already had monitoring equipment set up in the Aleutians on nearby volcanoes, and they were able to use microphone arrays to gather auditory data from Bogoslof’s eruptions.

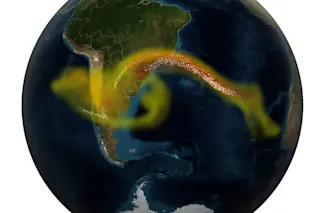

In addition, they relied on an existing network of Very Low Frequency (VLF) radio wave detectors to watch for lightning. In addition to bright flashes of light, lightning strikes also produce electromagnetic radiation in the VLF frequency, which can be detected over very long distances.

Thunderstruck

Using the VLF detectors, they catalogued hundreds of lightning strikes from an eruption on March 8, as well as some from another large eruption on June 10. Pairing the data with audio picked up the microphones, they got a surprise. In the midst of the low rumblings that accompany an eruption, they heard a series of cracks and claps that stood out clearly. The sounds matched up to periods of intense lightning in the clouds, they say, meaning that they were almost certainly thunder, and continued even after the volcano had stopped erupting. You can hear recordings of the eruption and resulting thunder here.

Additionally, the thunderclaps followed observations of lightning by about three minutes — exactly the amount of time it would take the sound to travel 40 miles from Bogoslof to the microphones. What’s more, the thunder originated from a slightly different location than the noises from the eruption, which would be expected as the lightning would form above the volcano.

Though confirming a phenomenon that was previously only rumor is nice, the researchers say their findings will help demystify some of the behaviors of volcanic ash clouds as well. Listening for thunder will give them a better idea what’s going on inside the massive plumes, and that could help tell them both how big the cloud is, and how dangerous it might be.