The stunning biodiversity of a "coral" reef. Photo by Laura D Rising carbon dioxide levels in our atmosphere are changing Earth's climate at an unprecedented rate. Not only is our planet getting warmer on average—in the oceans, a chemical reaction spurred by dissolved CO2 is altering water chemistry, causing a decrease in pH. This effect of climate change, called ocean acidification, can dissolve the calcium carbonate foundations of coral reefs and other calcifying organisms, making it impossible to build and maintain healthy reefs. Luckily, recent studies on how corals react to lower pHs has given scientists hope that they may be more resilient than previously thought. However, to truly understand how reefs will respond to climate change, we have to look at more than just corals. Reefs are complex ecosystems, the bases of which are comprised of so much more than corals. There are other species which act as calcifiers, adding to the carbonate foundation (such as crustose coralline algae). The contribution of these non-coral species to reef growth, called secondary accretion, helps shape the surface and guide the settlement of larval corals. There are also species that eat away at the reef, including many worms and sponges. These bioeroders can weaken reef structures until they crumble apart. Whether a reef grows or shrinks over time depends on the interplay between its corals, other reef-builders, and the burrowing organisms which eat their way through the reef's carbonate foundation. The corals have received a lot of scientific attention, with many laboratories around the world conducting field and lab experiments in an attempt to predict how these essential species will react to the higher temperatures and the altered seawater chemistry that will come with our changing climate. Relatively less attention has been paid to the other species that also determining the size and shape of the reef—in part because such studies are harder to design. After all, there could be hundreds of species on a reef contributing to secondary accretion or bioerosion. While it's somewhat simple to take a coral into a lab tank and monitor changes as you tinker with water parameters, it's impossible to do the same to a whole reef at once.

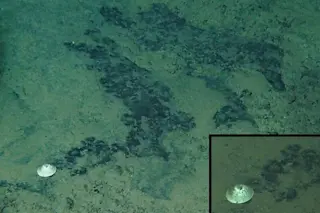

Nyssa Silbiger collecting one of the blocks after its year at sea. Credit: NOAA So instead, Nyssa Silbiger and her colleagues got creative. She precisely cut calcium carbonate blocks from the skeletons of dead Porites corals and placed them along a a natural environmental gradient in Kāne‘ohe Bay, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, which varied in depth, temperature, nutrients, and pH. For a year, she let the organisms in the area do as they pleased. Encrusting organisms added to the blocks, while boring species cut through them. Then, she removed the blocks and determined how the environmental variables related to the block's final size and shape. Previous studies measured discrepancies in weight of similar blocks to get a vague understanding of change, but Silbiger wanted something more precise. To get a detailed picture, Silbiger and her team repurposed a technology designed for medical uses called microcomputed tomography, or μCT. If you've ever gotten a "cat" scan, then you've essentially experienced the same imaging technology; CT technologies allow for the examination of objects from the inside out. A CT scan of your head allows doctors to look for brain injuries by creating a three dimensional version of your brain and skull. Similarly, Silbiger and her colleagues were able to use μCT to generate three-dimensional images of the blocks before and after a year in the field.

3D reconstruction of a µCT scan of an experimental coral block after a one-year deployment in Kāne‘ohe Bay, Hawai‘i. Video by Nyssa Silbiger at UH Mānoa and Mark Riccio at the Cornell Unversity µCT Facility for Imaging and Preclinical Research.

Video by Nyssa Silbiger and Mark Riccio The results, published this month in PLoS ONE, connected temperature and pH to alterations of the blocks. Silbiger and her colleagues found that accretion and erosion responded differently to the various environmental variables, with erosion in particular much more strongly linked to seawater acidity than anyone had previously seen. Such differences are important to note for scientists seeking to predict how reefs will respond to future changes. “Models predicting the impact of climate change on coral reefs often lump accretion and erosion processes together”, said Silbiger, “but the fact that we found different drivers means that we need to think more deeply about the predictive models we're using.” In addition to the findings, this study was a test of the use of µCT for studying reef growth and shrinkage—a test which µCT passed with flying colors, paving the way for future studies. “We are able to assess the addition or removal of calcium carbonate at a resolution of 100 micrometers—approximately the thickness of a human hair,” said Silbiger. “There is so much that we can learn about coral reefs using µCT scans. My colleagues and I are mining all the information we can from this exciting technology.” But more importantly, the findings underscore just how vulnerable our planet's reefs are to our changing climate. “The results of our study are sobering because it seems that even if corals can adapt, acclimatize or withstand changing ocean pH, bioerosion of the reef framework will still continue to increase,” Silbiger said. Still, she's optimistic about the future. “I think there's a lot more to learn before we can say that reefs are going to disappear,” Silbiger said.

Citation: Silbiger NJ, Guadayol Ò, Thomas FIM, Donahue MJ (2016). A Novel μCT Analysis Reveals Different Responses of Bioerosion and Secondary Accretion to Environmental Variability. PLoS ONE 11(4): e0153058. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153058