Humans have an extraordinary capacity for selflessness. We often help complete strangers who are unrelated to us, who we may never meet again and who are unlikely to be able to return the favour. More and more, we are being asked to behave in selfless ways to further the common good, not least in the race to tackle climate change.

Given these challenges, it's more important than ever to understand the roots of cooperative behaviour. From an evolutionary point of view, it can be a bit puzzling because any utopic society finds itself vulnerable to slackers, who can prosper at the expense of their peers while contributing little themselves. When cheaters can all-too-easily prosper, it should be difficult for altruistic behaviour to persist.

Nonetheless, persist it does, and psychological experiments suggest that punishment is part of the glue that binds a cooperating society together. In general, we as a species value fair play and we loathe freeloaders, to the extent that we are all too willing to sacrifice our own gains in order to punish cheats.

But punishment is a two-way street and not all freeloaders take castigation lightly. They can easily get their own back on altruists out of revenge or a simple desire to take down some do-gooders. This 'antisocial punishment' is often ignored by social science research but a new study shows that it has the ability to derail the high levels of cooperation that other more fairer forms of punishment can help to entrench.

Game on

To study the links between punishment and cooperation, Benedikt Herrmann from the University of Nottingham watched the behaviour of university students from 16 cities around the world as they played a psychological game. He picked cities as diverse as Boston, Copenhagen and Riyadh to compare behaviour across a wide range of cultures, but worked with upper- or middle-class university students to study people from comparable social groups.

The students played a 'public goods game' in groups of four, anonymously and over computers. Each was given 20 tokens and told to place a number of their choice into a public account. This joint money gained interest by a factor of 1.6 and was distributed equally between the players, after which each individual pot was converted into real money. The game went on for ten rounds and after each one, the players were informed about the moves that their peers made.

From the groups' point of view, the best decision was for everyone to put in their full pot, and walk away with 32 tokens apiece. However, each individual player would do best by putting nothing in and nonetheless reaping a share of their peers' contributions - they would then receive 44 tokens for no personal risk. But if none of the players contributed anything, no one would profit and everyone would stay on 20 tokens apiece.

In reality, the groups showed very different degrees of cooperation, with players initially chipping in between 8 and 14 tokens from their total of 20. However, as they became aware of spongers in their midst, they became less motivated to chip in themselves and in all groups, the contributions dwindled over time until players were only putting in a measly average of 5 tokens each.

Crime and punishment

Herrmann then repeated the experiment with a twist. After each round, players had the chance to anonymously punish their peers with a fine of up to 30 tokens, which were then removed from the pot. This action came at a cost, and each punisher had to pay one token for every three they removed from someone else.

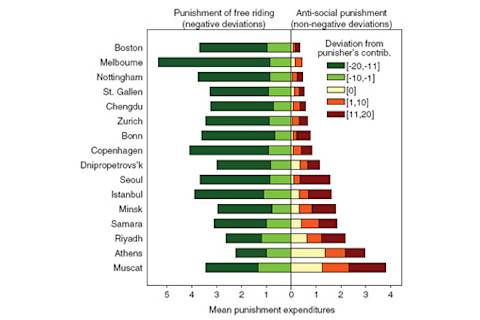

With this opportunity for enforcement, the situation changed dramatically. Students in all 16 groups were more than happy to sacrifice their own tokens to punish freeloaders, and all the groups did so in very similar ways, doling out the heaviest fines to those who contributed the fewest tokens to the pot. Faced with the imminent threat of punishment, freeloaders lost the impetus to cheat and none of the groups showed a breakdown in cooperation.

But Herrmann also saw substantial differences in the way that the 16 groups reacted to punishments. In some countries like the USA, the UK and Australia, admonished cheaters mostly accepted their punishment and started to donate more over time. As a result, cooperative behaviour became more common and by the end of the tenth round, many of the groups were chipping in about 70-90% of their pot.

In contrast, some freeloaders took less well to having their wrists slapped and sought revenge on their punishers, regardless of how generous they had been. Indeed, players who were punished most heavily were the more likely to exact antisocial punishments on their peers.

This practice of 'antisocial punishment' was largely absent in many groups but it was a frequent tactic among players from countries like Saudi Arabia, Greece and Oman, who were just as likely to castigate altruists as scroungers. Even in these groups, levels of cooperation didn't decline but they never climbed to the levels of groups that only punished freeloaders. By the end of the tenth round, players from Athens and Riyadh were only contributing about 33% of their earnings.

These international differences in cooperation were reflected in the final earnings of the different groups. The most generous players (from Boston) walked away with over 2.5 times more money than the least generous ones (from Muscat).

Roots of punishment

Herrmann found that antisocial punishment was more common in countries where the ethic of cooperation is less ingrained. He measured the attitudes of the 16 countries included in the game, using data from the World Values Survey, which asked people about their views on whether activities like tax evasion, benefit fraud and fare-dodging are ever justified.

The 16 scores spanned almost the entire worldwide range of attitudes, and Herrmann found that countries that show greater tolerance for these freeloading actions were more likely to exact antisocial punishment. Conversely, he reasoned that societies with strongly ingrained views on the value of cooperation are more likely to abhor free-riding, applaud altruism and avoid antisocial punishment.

Herrmann also found that antisocial punishment was less common in countries that trusted their courts, police and other law enforcement officials to be effective, fair and free from corruption. On the other hand, if people believed that the rule of law was weak (as measured by the World Bank's "Rule of Law" index) they were more likely to seek revenge against those they felt had wronged them. In such situations, antisocial punishment was not only more common but meted out more harshly.

As Herrmann's work shows, the degree of antisocial punishment in a society can have a strong impact on how cooperative it is and in turn, how economically successful it is. The results of the game suggest that a country's economic prowess depends not just on a naked desire for material gain, but also on its moral attitude towards cooperation.

In a related commentary, Herbert Gintis attempted to equate this ethic of cooperation with democracy, noting that six of the countries with the lowest levels of antisocial punishment also score highly in rankings of civil liberties, political rights and freedom of the press. In contrast, authoritarian societies tend to show higher levels of antisocial punishment.

But this delineation is perhaps too simplistic. China, for example, strongly bucks the trend in that it scores poorly in terms of the democratic markers listed above, but still shows relatively low levels of antisocial punishment and accordingly, is one of the world's fastest growing economies.

Reference: Herrmann, B., Thoni, C., Gachter, S. (2008). Antisocial Punishment Across Societies. Science, 319(5868), 1362-1367. DOI: 10.1126/science.1153808