Fossil or faux pas? A 2016 study that interpreted rock anomalies as the oldest evidence of life on our planet got it wrong, say researchers behind a new analysis of some of the same rock. The deformities aren’t relics of early microbial life, says the team, but rather a snapshot of geological forces shaping and reshaping our world.

The race to find the very first sign of life on Earth is one of the more heated contests in science — even though, for some, it lacks the glamour of hunting dinosaur fossils or uncovering our own hominin family tree. Instead, the work typically involves analyzing the oldest rocks on the planet for geochemical signatures and trace fossils such as stromatolites, which are layered structures that are formed by microbial activity and deposited in sediment.

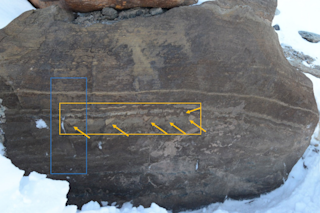

Several contenders for evidence of the earliest life have emerged in recent years. Just in 2017, ...