The oldest known figurative cave art painting in the world may be a 40,000-year-old rendering of a species of wild cattle found in a Borneo cave by a group of Griffith University researchers.

It is considerably older than a 35,400-year-old pig-deer painting discovered by the same team a few years ago in a cave located on Sulawesi, another island in Indonesia.

These recent Indonesian cave art discoveries are significant because they essentially rewrite the history of art and human cultural achievement. Until a few years ago, it was believed that Europe was home to the oldest figurative works, artwork that clearly depicts something from the real world. The revelation that a Palaeolithic rock art tradition was established in Indonesia at least 40,000 years ago challenges the long-held belief that Europe was the cradle of early artistic creativity. Rather, ice age artists in Indonesia were creating figurative art at the same time their European counterparts were doing so, 8,000 miles away.

“It now seems that two early cave art provinces arose at a similar time in remote corners of Palaeolithic Eurasia: one in Europe, and one in Indonesia at the opposite end of this ice age world,” said Adam Brumm, a Griffith archaeologist involved in the study.

A Treacherous Mission

The limestone caves located in the East Kalimantan mountains of Borneo were suspected to be home to thousands of prehistoric paintings and other forms of early art. Until now, the paintings haven’t received much study due to the remote and treacherous location of the caves.

“To go to the main site, Gua Saleh, we have to go up a river by canoe and then we have to walk for about four days in dense jungle. The cave is situated up a mountain, so it’s quite a hike. The cave opens up to a secret untouched valley on the other side of the mountain,” said Maxime Aubert, a Griffith archaeologist involved in the study.

Upon making it to the site, the researchers were faced with their next challenge: finding images covered by calcite, a calcium carbonate mineral. Calcite samples are necessary for researchers to use Uranium series dating — an approach that is more accurate than radiocarbon dating when it comes to classifying archeological finds older than 40,000 years old.

“Radiocarbon dating is usually used to date the pigment layer itself,” Aubert said. “Its been applied in France, for example, to date the charcoal drawings in the Chauvet cave. The problem is that it only provides a maximum age and the date is for the charcoal, not the marking event.”

The researchers analyzed several artworks found in the remote Borneo caves and were able to group them into three distinct styles based on their common attributes and age.

Red-orange renderings of animals (mostly wild cattle) and hand stencils were common in the oldest phase, dating to between 40,000 and 52,000 years ago. This phase is likely when the oldest known figurative painting was created on a wall in the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave.

From the Animal World to the Human World

A second phase of rock art emerged 20,000 years ago and coincides with the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum. Instead of depicting animals, artists began to paint humans, intricate motifs and hand stencils using mulberry-colored pigment. The transition to depicting the human world hints a significant change occurred in the region, according to researchers.

Composition of mulberry-colored hand stencils superimposed over older reddish-orange hand stencils. The two styles are separated in time by at least 20,000 years. (Credit: Kinez Riza)

Kinez Riza

“This possibly reflects the arrival of another wave of humans, or a natural evolution in art development coinciding with the onset of the Large Glacial Maximum and a potential increase in population size in that part of Borneo, owing to more favorable conditions for humans,” Aubert said.

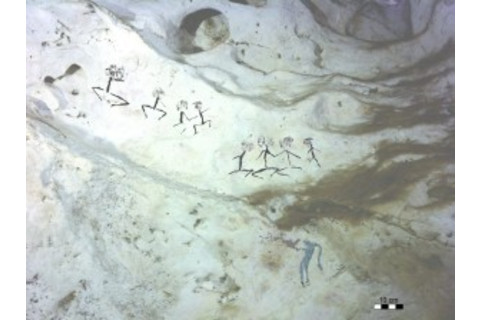

The final phase depicts human figures, boats and geometric designs using black pigment — likely charcoal, Aubert said.

Human figures from East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. This style is dated to at least 13,600 years ago but could possibly date to the height of the last Glacial Maximum 20,000 years ago. (Credit: Pindi Setiawan)

Pindi Setiawan

Interestingly, similar transitions in styles of art have been observed in Europe at the same time they were happening in Borneo.

“I think we’re starting to see a pattern where cave art seems to have developed and evolved more or less at the same time and in a similar way at the opposite side of the world,” Aubert said.

There’s likely more rock art to be found in the region — and much more to learn about the artists that created the images thousands of years ago. The research team will return to the area next year to begin archeological excavations to gain insight into who these unknown artists were and the worlds they lived in.

“Rock art provides an intimate window into the past,” Aubert said. “We can see how people lived a long time ago in a way that archaeology can’t provide. It’s like they’re still talking to us today.”

The Griffith University study was published in Nature this week.