A new ridiculous rumor is spreading around the internets. According to conspiracy theorists, the recent outbreak of Zika can be blamed on the British biotech company Oxitec, which some are saying even intentionally caused the disease as a form of ethnic cleansing or population control. The articles all cite a lone Redditor who proposed the connection on January 25th to the Conspiracy subreddit. "There are no biological free lunches," says one commenter on the idea. "Releasing genetically altered species into the environment could have disastrous consequences" another added. "Maybe that's what some entities want to happen...?" For some reason, it's been one of those months where random nonsense suddenly hits mainstream. Here are the facts: there's no evidence whatsoever to support this conspiracy theory, or any of the other bizarre, anti-science claims that have popped up in the past few weeks. So let's stop all of this right here, right now: The Earth is round, not flat (and it's definitely not hollow). Last year was the hottest year on record, and climate change is really happening (so please just stop, Mr. Cruz). And FFS, genetically modified mosquitoes didn't start the Zika outbreak. Background on Zika The Zika virus is a flavivirus closely related to notorious pathogens including dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile virus. The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes in the genus Aedes, especially A. aegypti, which is a known vector for many of Zika's relatives. Symptoms of the infection appear three to twelve days post bite. Most people are asymptomatic, which means they show no signs of infection. The vast majority of those who do show signs of infection report fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes), according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. After a week or less, the symptoms tend to go away on their own. Serious complications have occurred, but they have been extremely rare. The Zika virus isn't new. It was first isolated in 1947 from a Rhesus monkey in the Zika Forest in Uganda, hence the pathogen's name. The first human cases were confirmed in Uganda and Tanzania in 1952, and by 1968, the virus had spread to Nigeria. But since then, the virus has found its way out of Africa. The first major outbreak occurred on the island of Yap in Micronesia for 13 weeks 2007, during which 185 Zika cases were suspected (49 of those were confirmed, with another 59 considered probable). Then, in October 2013, an outbreak began in French Polynesia; around 10,000 cases were reported, less than 100 of which presented with severe neurological or autoimmune complications. One confirmed case of autochthonous transmission occurred in Chile in 2014, which means a person was infected while they were in Chile rather than somewhere else. Cases were also reported that year from several Pacific Islands. The virus was detected in Chile until June 2014, but then it seemed to disappear. Fast forward to May 2015, when the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an alert regarding the first confirmed Zika virus infection in Brazil. Since then, several thousand suspected cases of the disease and a previously unknown complication—a kind of birth defect known as microcephaly where the baby's brain is abnormally small—have been reported from Brazil. (It's important to note that while the connection between the virus and microcephaly is strongly suspected, the link has yet to be conclusively demonstrated.) Currently, there is no vaccine for Zika, though the recent rise in cases has spurred research efforts. Thus, preventing mosquito bites is the only prophylactic measure available. The recent spread of the virus has been described as "explosive"; Zika has now been detected in 25 countries and territories. The rising concern over both the number of cases and reports of serious complications has led the most affected areas in Brazil to declare a state of emergency, and on Monday, The World Health Organization's Director-General will convene an International Health Regulations Emergency Committee on Zika virus and the observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations. At this emergency meeting, the committee will discuss mitigation strategies and decide whether the organization will officially declare the virus a "Public Health Emergency of International Concern." GM to the Rescue

Aedes aegypti: the invasive mosquito in Brazil that carries Zika virus and other awful diseases. Photo by James Gathany, c/o the CDC The mosquito to blame for the outbreak—Aedes aegypti—doesn't belong in the Americas. It's native to Africa, and was only introduced in the new world when Europeans began to explore the globe. In the 20th century, mosquito control programs nearly eradicated the unwelcome menace from the Americas (largely thanks to the use of the controversial pesticide DDT); as late as the mid 1970s, Brazil and 15 other nations were Aedes aegypti-free. But despite the successes, eradication efforts were halted, allowing the mosquito to regain its lost territory.

The distribution of Aedes aegypti in the Americas in 1970 and 2002, from the Centers for Disease Control Effective control measures are expensive and difficult to maintain, so at the tail end of the 20th century and into the 21st, scientists began to explore creative means of controlling mosquito populations, including the use of genetic modification. Oxitec's mosquitoes are one of the most exciting technologies to have emerged from this period. Here's how they work, as I described in a post almost exactly a year ago:

While these mosquitoes are genetically modified, they aren’t “cross-bred with the herpes simplex virus and E. coli bacteria” (that would be an interkingdom ménage à trois!)—and no, they cannot be “used to bite people and essentially make them immune to dengue fever and chikungunya” (they aren’t carrying a vaccine!). The mosquitoes that Oxitec have designed are what scientists call “autocidal” or possess a “dominant lethal genetic system,” which is mostly fancy wording for “they die all by themselves”. The males carry inserted DNA which causes the mosquitoes to depend upon a dietary supplement that is easy to provide in the lab, but not available in nature. When the so-called mutants breed with normal females, all of the offspring require the missing dietary supplement because the suicide genes passed on from the males are genetically dominant. Thus, the offspring die before they can become adults. The idea is, if you release enough such males in an area, then the females won’t have a choice but to mate with them. That will mean there will be few to no successful offspring in the next generation, and the population is effectively controlled.

Male mosquitoes don't bite people

, so they cannot serve as transmission vectors for Zika or any other disease. As for fears that GM females will take over: less than 5% of all offspring survive in the laboratory without tetracycline, and as Glen Slade, director of Oxitec's Brazilian branch notes, those are the best possible conditions for survival. "It is considered unlikely that the survival rate is anywhere near that high in the harsher field conditions since offspring reaching adulthood will have been weakened by the self-limiting gene," he told me. And contrary to what the conspiracy theorists claim, scientists have shown that tetracycline in the environment doesn't increase that survival rate. The proponents of this conspiracy theory say that an internal Oxitec memo showed they could survive as much as 15% if fed cat food containing tetracycline, as if it was some secret information being covered up by the company. But that number was reported in their paper on the mosquitoes in 2013, while it was also noted that such a level in was unlikely outside of the lab. Oxitec further went out and tested to see if the environmental levels in Brazil were high enough to raise survival rates, and they weren't. As Simon Warner, Chief Scientific Officer for Oxitec, explains:

Researchers from the University of Campinas, Brazil, Imperial College London and outside CROs worked together with Oxitec to assess whether exposure to tetracycline in the environment could affect survival levels of OX513A. The highest levels of tetracycline found in mosquito breeding sites or nearby locations were below the minimal level of tetracycline needed to produce any change in survival rates. What if a bowl of pet food and water was available for OX513A in Brazil? Firstly the bowl would need to be left uninterrupted for a couple of weeks for the OX513A to develop. Most pet owners clean their pet’s food more frequently and health officials advise that no standing containers of water be left for Aedes aegypti to breed in. If the OX513A did develop then as soon as they flew away from the dog bowl they would no longer have access to tetracycline and the self-limiting gene would become active and they would die. It would be impossible for them to continue to breed and become self-sustaining without access to doses of tetracycline.

Brazil, a hotspot for dengue and other such diseases, is one of the countries where Oxitec is testing their mozzies—so far, everywhere that Oxitec's mosquitoes have been released, the local populations have been suppressed by about 90%. Genetics Schmenetics (added Feb 2-4) Oliver Tickell, journalist and editor of the Ecologist, came out with a point by point "hypothesis" seeking to legitimize the conspiracy theory after my initial post. It hinges on his claim that "The promiscuous piggyBac transposon now present in the local Aedes aegypti population takes the opportunity to jump into the Zika virus, probably on numerous occasions." But we know for a fact this isn't the case. First off, it's not possible. Tickell attempts to make a convoluted connection between the gene insertion system used to add the genetic modification—PiggyBac—and the an increase in virulence in Zika. He cites a dodgy anti-GM website (calling it a "review article", when it is not a scientific journal article of any kind and has not passed peer review) which claims that PiggyBac moves around all the time. But for the risk assessment to get the permits and approval of the local Brazilian government, Oxitec had to demonstrate that their insertion doesn't move. They had to demonstrate that the insertion is stable and follows "Mendelian inheritance" (which means it stays in the same place on the chromosome). And they did, to the satisfaction of the regulators—you can read the risk assessment yourself. As Simon Warner, Chief Scientific Officer for Oxitec, explains:

The OX513A mosquito has now been through more than 100 generations and there has never been an instance where the self-limiting gene has behaved as if it were a jumping gene. In human terms, 100 generations is equivalent to a period of time from the early AD years to the present day. Additionally, the self-limiting gene confers a strong selective disadvantage to any insect that carries it, so in the impossible event that the gene did move, there would be no selection that would mean that gene could persist and spread in any population.

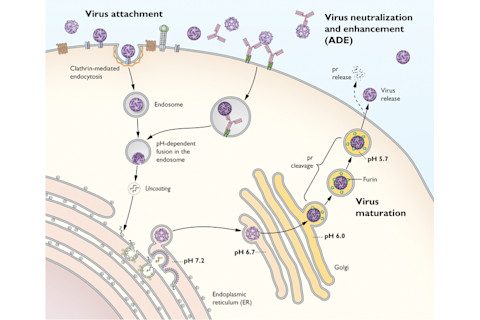

But most importantly, it's not possible for a PiggyBac transposon to move into the Zika genome because PiggyBac is a double-stranded DNA element which only inserts into double-stranded DNA at specific sites (TTAA elements). Zika has no DNA. It's a single strand RNA virus roughly 10.8kb in size which never goes through a DNA phase when replicating, nor does it enter the cellular nucleus where the mosquito genome is located.

How flaviviruses like Zika replicate, courtesy of the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Virologist Kenneth Stedman, who recently published a review on the interaction between viral genes and genomes, explained:

There are a quite small, but not insignificant, number of examples of partial genomes of RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses that have been incorporated into cellular DNA genomes and even fewer examples of a gene from a purely RNA virus which appears to have been acquired by an ssDNA virus (which we originally discovered, see Diemer and Stedman, 2012). However, there are NO examples of the inverse, that is to say purely RNA viruses or ssDNA viruses picking up genes from host genomes. This is not from want of trying, there have been extensive sequencing efforts on purely RNA viruses, including Zika, and none of these viruses have been found to contain cellular genes. There are 2 reasons for the unidirectionality, purely RNA viruses, such as the flaviviruses, of which Zika is a member, have RNA genomes that make copies of their genome from RNA, there is no DNA intermediate and they use a special virus-specific RNA polymerase to do this. The second is that most ssRNA viruses (and flaviviruses in particular) are very constrained in terms of how much RNA they can hold, so they are extremely unlikely to pick up any "extra" genes without causing the virus to be non-viable. On the other hand, cellular genomes are not under such constraints and can acquire RNA and ssDNA virus genes by fascinating mechanisms (some of which are outlined in my Annual Reviews of Virology paper).

To Stedman's last point: the transposon used by Oxitec is 8.4kb - so almost the same size as the entire Zika virus genome! But perhaps most to the point, mosquito genes, from genetic modification or otherwise, are not present in the Zika virus in Brazil. The whole genome of the Zika virus is tiny, and it's easily sequenced—which is exactly what scientists in Brazil have done. That means there was no "jumping DNA" responsible, period. Given the importance of this outbreak, scientists published their sequencing results as openly and as quickly as possible. I'll say it again: They did not find any transposons or mosquito genes of any kind. They did, however, find some interesting mutational changes which may explain why the outbreak in Brazil seems to be worse than previous outbreaks; the mutational changes may have led to an increase in viral titers. The family of viruses that Zika belongs to are known to cause birth defects in rare cases, including microcephaly, so an increase in viral titers could be sufficient to explain the sudden uptick in cases, especially when you consider the other confounding factors—factors which, as Oliviera Melo and his colleagues explain, include an increase in reporting (the more we look for a disease, the more we tend to find cases of it), a lack of childhood exposure to the virus in the outbreak areas (if you are infected by Zika as a kid, your body has some resistance or even immunity, so even if someone is exposed when pregnant, they don't have the same complications), or the rarity of the disease until now (it takes a very large number of cases to detect an increase in very rare complications). Wrong Place, Wrong Time Now that we've covered that, let's dig into the conspiracy theory as it was originally posted. We'll start with the main argument laid out as evidence: that the Zika outbreak began in the same location at the same time as the first Oxitec release:

Zika Outbreak Epicenter In Same Area Where GM Mosquitoes Were Released In 2015 https://t.co/0vvLWaueAxpic.twitter.com/38ZxhwBGgZ

— The D.C. Clothesline (@DCClothesline) January 29, 2016

Though it's often said, it's worth repeating: correlation doesn't equal causation. If it did, then Nicholas Cage is to blame for people drowning

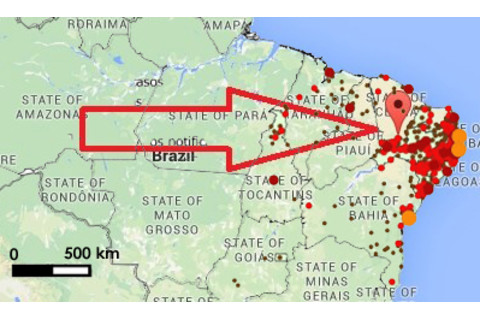

(Why, Nick? WHY?). But even beyond that, there are bigger problems with this supposed correlation: even by those maps, the site of release is on the fringe of the Zika hotspot, not the center of it. Just look at the two overlaid:

The epicenter of the Zika outbreak is clearly on the coast, hundreds of kilometers from the noted location. The epicenter of the outbreak and the release clearly don't line up—the epicenter is on the coast rather than inland where the map points. Epidemiologists have tracked the outbreak back to where it started, and now say that the Zika outbreak "almost certainly"

began in Recife, Brazil, a city almost 400 miles from the nearest Oxitec release location. There are no early cases, however few, from 400 miles inland; the viral outbreak started on the coast and then, as the disease spread, moved inland. If the Oxitec conspiracy theory is correct: how did a virus mutated in Juazeiro get 400 miles away before causing any microcephaly cases? I see a lot of people gloss over this, saying "well, what if the person infected by the mutant virus immediately drove to Recife" or hypotheses along those lines. Let's take a moment to think about how unlikely a scenario that is. The theory argues that there was a group of people in Juazeiro with Zika virus and that all of them had no signs whatsoever, because if they had gone to the doctor and had signs, those cases would be reported and we would know that Zika was there. Then one of those people had to be bitten by GM mosquitoes, even though the vast majority of female mosquitoes would be non-GM, while their viremia (the number of viruses in their blood stream) was high enough (but yet not high enough to cause symptoms). Then the virus has to mutate in that mosquito (see above on why that didn't happen), and then that mosquito has to bite another person and infect them. And THEN that person has to high tail it out of Juazeiro 400 miles to the coast before coming down with the illness, meanwhile, the virus in the Juazeiro population stays hidden with no one getting symptoms until after the outbreak everywhere else spreads. Does that sound like a plausible scenario? To claim that anything done in Juazeiro caused an outbreak to occur 400 miles away is the same as claiming that whatever is done in Phoenix, AZ is directly responsible for disease outbreaks in Los Angeles, CA. In fact, those two cities are nearly 50 miles closer together than Juazeiro, BA and Recife, PE:

If Recife and Juazeiro are "the same area"... Juazeiro-Recife: 395.9 mi. LA-Phoenix: 357.2 mi. Boston-DC: 394.2 mi pic.twitter.com/MtEJGVa2bw

— Dr. Christie Wilcox (@NerdyChristie) February 2, 2016

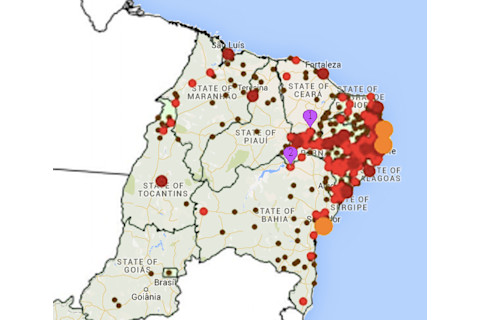

That's not even mentioning that the location on the map isn't where the mosquitoes were released. That map points to Juazeiro de Norte, Ceará, which is a solid 300 km away from Juazeiro, Bahia—the actual site of the mosquito trial. That location is even more on the edge of the Zika-affected area:

1: Juazeiro de Norte, the identified location in by conspiracy theorists. 2: Juazeiro, the actual location of Oxitec's release trial, about 300 km away and even further from the outbreak epicenter The mistake was made initially by the Redditor who proposed the conspiracy theory and has been propagated through lazy journalistic practices by every proponent since. Here's a quick tip: if you're basing your conspiracy theory on location coincidence, it's probably a good idea to actually get the location right. They're also wrong about the date. According to the D.C. Clothesline

:

By July 2015, shortly after the GM mosquitoes were first released into the wild in Juazeiro, Brazil, Oxitec proudly announced they had “successfully controlled the Aedes aegypti mosquito that spreads dengue fever, chikungunya and zika virus, by reducing the target population by more than 90%.”

However, GM mosquitoes weren't first released in Juazeiro, Bahia (let alone Juazeiro de Norte, Ceará) in 2015. Instead, the announcement by Oxitec was of the published results of a trial that occurred in Juazeiro between May 2011 and Sept 2012—a fact which is clearly stated in the methods and results of the paper that Oxitec was so excited to share

. A new control effort employing Oxitec mosquitoes did begin in April 2015, but not in Juazeiro, or any of the northeastern states of Brazil where the disease outbreak is occurring. As another press release from Oxitec states, the 2015 releases of their GM mosquitoes were in Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil:

Following approval by Brazil’s National Biosafety Committee (CTNBio) for releases throughout the country, Piracicaba’s CECAP/Eldorado district became the world’s first municipality to partner directly with Oxitec and in April 2015 started releasing its self-limiting mosquitoes whose offspring do not survive. By the end of the calendar year, results had already indicated a reduction in wild mosquito larvae by 82%. Oxitec’s efficacy trials across Brazil, Panama and the Cayman Islands all resulted in a greater than 90% suppression of the wild Ae. aegypti mosquito population–an unprecedented level of control. Based on the positive results achieved to date, the ‘Friendly Aedes aegypti Project’ in CECAP/Eldorado district covering 5,000 people has been extended for another year. Additionally, Oxitec and Piracicaba have signed a letter of intent to expand the project to an area of 35,000-60,000 residents. This geographic region includes the city’s center and was chosen due to the large flow of people commuting between it and surrounding neighborhoods which may contribute to the spread of infestations and infections.

Piracicaba, for the record, is more than 1300 miles away from the Zika epicenter:

1: Juazeiro de Norte, the identified location in by conspiracy theorists. 2: Juazeiro, the actual location of Oxitec's 2011-2012 trial, and 3: Piracicaba, the location where mosquitoes began to be released starting in April 2015, more than 2,000 km from the disease epicenter. So not only did the conspiracy theorists get the location of the first Brazil release wrong, they either got the date wrong, too, or got the location of the 2015 releases really, really off. Either way, the central argument that the release of GM mosquitoes by Oxitec coincides with the first cases of Zika virus simply doesn't hold up. And, if the nails aren't already in the coffin, then there's this: when Zika hit French Polynesia in 2014, they also saw a trend of increasing microcephaly.

There are no GM mosquitoes in French Polynesia, then or now: so how did they end up with the supposed "mutant" virus that caused birth defects? And just for those who aren't convinced Zika has anything to do with this: if the virus isn't involved, and the mosquitoes are "mutating" people directly (also not possible, as I explained in my post last year

on why they are not damaging), then why are there more cases from areas where there aren't GM mosquitoes than areas where they were released? And where are there microcephaly cases in the Cayman Islands, or other places where these mosquitoes have been tested? Scientists Speak Out As this ludicrous conspiracy theory has spread, so, too, has the scientific opposition to it. "Frankly, I'm a little sick of this kind of anti-science platform," said vector ecologist Tanjim Hossain

from the University of Miami, when I asked him what he thought. "This kind of fear mongering is not only irresponsible, but may very well be downright harmful to vulnerable populations from a global health perspective." Despite the specious allusions

made by proponents of the conspiracy, this is still not Jurassic Park, says Hossain. "We have a problem where ZIKV is spreading rapidly and is widely suspected of causing serious health issues," he continued. "How do we solve this problem? An Integrated Vector Management (IVM) approach is key. We need to use all available tools, old and new, to combat the problem. GM mosquitoes are a fairly new tool in our arsenal. The way I see it, they have the potential to quickly reduce a local population of vector mosquitoes to near zero, and thereby can also reduce the risk of disease transmission. This kind of strategy could be particularly useful in a disease outbreak 'hotspot' because you could hypothetically stop the disease in its tracks so to speak." Other scientists have shared similar sentiments. Alex Perkins, a biological science professor at Notre Dame, told Business Insider

that rather than causing the outbreak, GM mosquitoes might be our best chance to fight it. "It could very well be the case that genetically modified mosquitos could end up being one of the most important tools that we have to combat Zika," Perkins said. "If anything, we should potentially be looking into using these more." Brazilian authorities couldn't be happier with the results so far, and are eager to continue to fight these deadly mosquitoes by any means they can. "The initial project in CECAP/Eldorado district clearly showed that the 'friendly Aedes aegypti solution' made a big difference for the inhabitants of the area, helping to protect them from the mosquito that transmits dengue, Zika and chikungunya," said Pedro Mello, secretary of health in Piracicaba. He notes that during the 2014/2015 dengue season, before the trial there began, there were 133 cases of dengue. "In 2015/2016, after the beginning of the Friendly Aedes aegypti Project, we had only one case." It's long past time to stop villainizing Oxitec's mosquitoes for crimes they didn't commit. Claire Bernish

, Mirror

and everyone else who has spread these baseless accusations: I'm talking to you. The original post was in the Conspiracy subreddit—what more of a red flag for "this is wildly inaccurate bullsh*t" do you need? (After all, if this is a legit source, where are your reports on the new hidden messages in the $100 bill

? or why the Illuminati wants people to believe in aliens

?). It's well known that large-scale conspiracy theories are mathematically challenged

. Don't just post whatever crap is spewed on the internet because you know it'll get you a few clicks. It's dishonest, dangerous, and, frankly, deplorable to treat nonsense as possible truth just to prey upon your audience's very real fears of an emerging disease. You, with your complete lack of integrity, are maggots feeding on the decay of modern journalism, and I mean that with no disrespect to maggots. Update February 2, 2016 has been moved into the text for flow and streamlining on February 4. My statement about my language choice: Some have suggested that calling those who have uncritically spread the conspiracy theory "maggots" was inappropriate. It was more of a metaphor than name-calling, but I will concede: it was uncalled for to insult fly larvae in such a manner. I apologize to young dipterans everywhere.