Looters have never been a problem at the ruins of Cerén in the lush Zapotitán Valley of El Salvador. It’s not that the security is tight or that the site is especially remote. Cerén is just an hour’s drive from the capital, San Salvador, through hills of impossibly vivid greens and a sky so blue and pure you think you died and woke up in a Cheer commercial. No, it’s more that there isn’t, barring wheelbarrows and fancy German tape measures, anything to loot. No jade figurines, no hammered gold. The artifact list from this Mesoamerican ruin reads something like this: corncob, thatch fragment, carbonized bean.

While there is nothing remarkable about a bean, a 1,400-year-old bean is altogether another matter. Under normal conditions, organic matter in the tropics decomposes in a few months. Unless, as with Cerén, something extraordinary takes place to preserve it.

On a summer evening some 14 centuries ago, in the quiet hours between dinner and sleep, an underground storm began brewing close to Cerén. There must have been some sort of warning, a billow of steam or an ominous trembling, because something convinced the Cerén villagers, just a half mile away, to drop what they were doing and run.

It was a wise decision. Within days, their homes had disappeared, buried beneath 16 feet of scalding wet volcanic ash. The eruption did not merely unleash a slow molten ooze. The pressure of the shifting magma blew open the Earth, forming the volcanic cone, Loma Caldera. On the way to the surface, molten rock hit water, creating a blast of steam and hot ash that broadsided Cerén. Loma Caldera’s tantrum continued for days. There were 14 separate explosions--some raining hail-size stones of ash, some launching 100-pound lava bombs of solidified magma. Cerén was entombed as its inhabitants left it: dinner dishes unwashed, mice in the corn bins, a duck tethered to a post.

And so it remained for some 1,400 years. In 1976, the owners of the land that covered Cerén decided to build a grain silo. In the course of leveling a hillside, a bulldozer operator struck the adobe wall of a Cerén home. The worker called the National Museum in San Salvador, which dispatched an archeologist. On seeing thatched roofing--which normally disintegrates in a decade or so--the archeologist proclaimed the structure to be recent and of no scientific value. Two years and several demolished buildings later, an archeologist and Mesoamerican scholar from the University of Colorado, Payson Sheets, visited the site and began poking around with his trowel. He’d heard that they’d found a number of old pots and a building buried under volcanic ash, which was surprising, since as far as he knew there hadn’t been any local eruptions over the past few centuries. So he thought he’d have a look. Instead of digging up plastic soda bottles and tinfoil, as he expected, he found Mayan pottery in the style of the Classic Period, A.D. 500 to 800. Carbon dating confirmed that Cerén was indeed an ancient site. Excavations began the following year.

In 1981 war evicted science. Excavations resumed in 1989, and Sheets returned to Cerén. This is his seventh season at the site.

At the moment, Sheets is sitting in the Cerén dig house, a cinder-block shoe box that serves as lodgings for himself, three graduate students, two artifact conservators, a half dozen lizards, and a thriving community of bloodsucking insects. Above Sheets’s head is a hole in the roof where an iguana fell through.

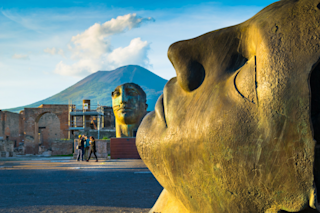

The topic is Pompeii. The media are forever calling Cerén the New World Pompeii, Sheets says with a sigh. I don’t like that term. At Pompeii, you didn’t get good organic preservation. The ash that buried Cerén was fine and moist; the ash that encased Pompeii was dry and came down in pea-size clumps. The two factors that determine quality of preservation, Sheets explains, are the moisture content of the ash and the size of its particles.

Still, there are obvious parallels. Cerén’s villagers--like Pompeii’s--left in a hurry, leaving behind the bulk of their possessions. But unlike the unlucky Pompeians, all Cerén’s residents seem to have escaped. So far, the only human remains at Cerén were teeth found among the remnants of a collapsed roof. (That was a bit puzzling until an Indian worker at the site pointed out that it’s a Central American custom to toss lost teeth onto the roof for good luck.) Plant and pottery remains, though, are abundant, and that’s what has allowed researchers to piece together a surprisingly detailed portrait of village life in the Classic Period.

Until Cerén, little was known about the Mesoamerican peasant class. Normally villages are abandoned gradually. Those who leave take everything with them, until all that remain to be studied are garbage and a few foundations. Partly for this reason, Mesoamerican archeology has tended to focus on the ruling elite. The preservation of palaces and pyramids is normally much better than that of the humble dwellings of commoners, says Sheets. Also, their massive construction makes them much easier to find.

A compounding factor is what Sheets calls the Indiana Jones syndrome. Archeologists have had a tendency to assume that, as Sheets puts it, it’s better to search for fancy jade masks and gold ornaments than to look for the things that were important and available to most of the population.

With any civilization that’s being studied, he says, if the households of commoners aren’t being investigated, you’ve eliminated the bulk of the population. It would be as if, one day hence, all that was known of United States society in the last decade of the twentieth century had been gleaned from the ruins of mansions and churches. How can you understand the society if you ignore most of the people?

Sometime in the 1970s archeologists broadened their focus, giving rise to a subdiscipline called household archeology. It’s like ethnography, says Sheets. Only we can’t interview people, so their possessions have to speak for them.

Household archeology is the science of dirty dishes and half- eaten corncobs. From finger swipes on the inside of a bowl, we know how the people of Cerén ate, and from remnants of food, we know what they ate. We know they made twine from agave fibers and, most likely, beer from fermented corn. We know they drew figures on the bathhouse walls. We know how many pots each family owned and where they put them when they didn’t feel like cleaning them. From the abundance of stone tools and painted gourds, we know that Cerén villagers probably traded goods with neighboring villages. And by examining the placement of bedrolls and the state of the cooking pots, we know that it was evening when Loma Caldera erupted and disrupted the villagers’ lives.

To date, Sheets and his crew have unearthed 11 buildings: several households, a sauna for ritual sweat baths, a public hall, and a structure in which a shaman worked. Twenty more have been located but have yet to be unearthed. The number of buildings leads Sheets to believe that Cerén was a thriving village, with perhaps a couple of hundred inhabitants.

Sheets has used every method short of dowsing to find buried structures. In the early years, he and his crew could be seen wandering the cornfields, banging hammers on steel plates and using a seismograph to time how long it took the shock waves to reach a series of buried seismic receivers. If the waves were passing through dirt or ash, they would arrive simultaneously. If some waves hit, say, an adobe building, those waves would travel faster; the packed clay of adobe bricks conducts sound waves better than relatively less dense ash or dirt. Ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity, variations on the same theme, yielded better results and have largely supplanted the seismograph.

Does Sheets plan to dig up every building he finds? How do you decide when enough’s enough? Sheets slaps at a mosquito. You know you’re pretty well done when things become routine. Surprises mean you’re still learning.

The latest surprise arrived during the unearthing of Structure 10. It contained a deer skull headdress, several religious artifacts, and a large food preparation area, leading Sheets to believe the building was a center for religious ceremonies and feasts.

There’d been an expectation, fueled by elite-driven archeology, that a small village wouldn’t have its own religious center, Sheets says. It was assumed that for religious things people would travel five kilometers to the pyramids at San Andrés, which was a political and economic hub for Mesoamerican culture. That’s clearly not the case.

Another surprise turned up in Household 2. The mystery artifact was a stack of organic layers with traces of red cinnabar paint. Sheets and his colleagues thought it might be a codex, a booklike document made of folded bark or deer hide. Fragments of codices had been found at centers of the Mayan elite, but never among the peasant class. The layers and the earth on which they lay were block-lifted and flown to Washington, D.C., to the Conservation Analytical Laboratory of the Smithsonian Institution (a customs nightmare second only to Sheets’s attempt to bring two kilos of fine white volcanic ash through Miami International Airport).

It wasn’t a codex. It was a storage vessel fashioned from a gourd. The dish had collapsed as it decomposed, leaving nothing but decorative paint and thin layers of rind. It’s unfortunate, says Sheets. A written text would have put to rest lingering uncertainties regarding the ethnicity of Cerén residents. Judging from the decorative styles of the ceramics and the division of the households into separate structures for cooking, sleeping, and storage, Sheets believes Cerén’s residents to have been either Maya or Lenca, a local group that may have adopted Mayan ways. Others have speculated that they might have been Xinca. Both the Lenca and Xinca groups occupied areas just a few miles outside traditional Mayan centers in present-day Guatemala and El Salvador. Sheets shrugs. If you think we know nothing of the Lenca--the Xinca? We barely know how to spell their name.

Whoever they were, the Cerén villagers had a good life. We had no idea people lived so well 14 centuries ago, says Sheets. They ate a nutritious and varied diet, including three varieties of beans, corn, squash, avocados, palm fruits, chilies, nuts, cacao, deer, and dog. They had so much food that they put it away for storage in a variety of woven and ceramic vessels. And there are signs that they traded cotton, and perhaps pottery, for obsidian from villages some five miles away.

If Loma Caldera erupted today, the mystery artifact--should archeologists one day return to the site--would be a thin tube attached to a handheld gas-powered engine. Closer inspection would reveal a tiny light at the end of the tube. After much head scratching, someone would identify the object as a proctoscope, circa 1985.

It’s for looking into ash holes, says Sheets. We are standing in the tin-roofed building that serves as Cerén’s lab, and he isn’t making a joke. The moist volcanic ash that settled around Cerén’s plants and organic debris packed so firmly that when the plants decomposed, cavities remained in the ash, their walls imprinted with the surface detail of what had once been there. So exact is the mold that one can fill it with dental plaster and, after a day’s hardening, dig away the ash to unveil a perfect plaster replica of the plant as it stood at the time the ash fell. Around the houses of the Cerén villagers lie plots of ghostly white plants, phantom corncobs and agaves from beyond the grave.

By affording a sneak preview of an ash hole’s configurations, the proctoscope has cut down significantly on dental supply bills. (Sheets went through some 400 pounds of dental plaster one year, provoking deep curiosity at the San Salvador dental supply store.) Not every plant or fallen tree branch need be preserved. Only if the scope reveals something new will the archeologists mix up a batch of plaster.

This afternoon workers have uncovered a row of mystery holes near Structure 3. Sheets fetches the proctoscope, a Fujionon brand that he bought used, but cleaned. He starts the engine and peers through the eyepiece. His guess is that it’s a savila plant, which would be a new species for Cerén. Identifying a plant from the inside out is an estimable talent. To the untrained eye, it looks like a hole in the dirt.

A pair of Salvadoran workers from Cerén’s modern-day counterpart, Joya de Cerén, are mixing plaster and water in small plastic bags, shaking them over one shoulder like bartenders mixing martinis. Here comes the high-tech part, says Sheets. One of the men bites off a tiny corner of the bag, fashioning a nozzle of the sort used to decorate cakes. He spits out the plastic and proceeds to squirt plaster down the hole.

These guys came up with the idea of using plastic bags, Sheets says. We were trying iv bottles, horse syringes. Nothing was working. It’s not the first time modern technology has been shamed by the homespun methods of the locals. A glitch in the ground-penetrating radar system, for example, is that interference from the electrical system of the truck that hauls the radar equipment can spoil the data. Sheets and his colleagues tried using oxen and an oxcart belonging to a Joya de Cerén villager instead of a truck. The resulting data were the cleanest anyone could recall seeing. The geophysicists who’d loaned us the instrument were begging us to bring them back an oxcart and a pair of oxen, says Sheets.

Some ancient tools at Cerén also have an edge on their modern counterparts. So impressed is Sheets with the carved obsidian blades found at the site that he’s gone into partnership with an eye surgeon to market a surgical version. They are, he says, sharper than surgical steel, or even diamond, blades.

The Cerén villagers were also experienced farmers, as the neatly planted and carefully tended fields surrounding the Cerén homes attest. It is a clear sign of permanent settlement, says Sheets. And it shows that they were as skilled in farming as they were in architecture.

Indeed, the residents of ancient Cerén seemed to know more about earthquake-resistant buildings than do the urban planners of San Salvador. They built homes with bajareque walls: adobe reinforced with sunflower-like Tithonia rotundifolia stalks, or varas--Mesoamerica’s answer to reinforced concrete. As Cerén structures are unearthed, they’re buttressed with laurel stakes, a modern equivalent of the Cerén varas, which are inserted into holes left by the decomposed stalks.

When a major earthquake shook El Salvador in 1986, it failed to damage Cerén’s structures. Without the reinforcement, Sheets says, we’d have been dead in the water. Case in point: the National Museum in San Salvador was severely damaged and eventually condemned. Luckily, the storehouse that contains the major artifacts from Cerén was unharmed.

Brian McKee, an archeology graduate student at the University of Arizona, sits down in a dirt path along which passes a continuous chorus line of men and red wheelbarrows. His task today is to oversee a pair of workers who are at this moment carefully spooning dirt, as though it were a precious metal, from a cloth sack into water. Six unopened sacks lean against the wall. The workers are performing flotation, which isn’t as refreshing as it sounds. What floats are bits of bone and plants and seeds, as opposed to dirt, which sinks. It is one of many meticulous tasks at Cerén. For every square meter of the site, archeologists tabulate exactly what is there and in what amounts.

Flotation is not, allows McKee, what you’d call the most exciting thing in the world.

Still, from this tedious sifting the researchers have gleaned a botanical surprise: one of the most common Cerén grass species, used by the ancient villagers for thatch, is extinct in the region today. Cerén’s ethnobotanist, David Lentz, presently off-site at the New York Botanical Garden, blames the disappearance of the species on the introduction of hardier grasses from Africa. These grasses are better adapted to herbivory than the native grasses of the New World, which has few native ungulates.

In Africa, says Lentz, if you want to be a grass, you have to be used to being chewed on. These poor local plants didn’t know what hit them. After the cattle and African grasses were introduced, it was sayonara to the local species.

Figuring out how Cerén villagers made their buildings is one problem. Figuring out how to preserve them is another. The biggest threat, says McKee, are the swings in seasonal humidity. In the rainy season the clay adobe absorbs moisture from the air and ground, causing the clay to swell. When the humidity falls, water evaporates from the clay, which shrinks back down. The repeated shrinking and expanding breaks chemical bonds, causing the clay to spall--archeology lingo for disintegrating into little bits and flaking off.

Mayan methods of preservation are helping. In a clearing outside the lab, workers can be seen pounding escobilla stems and leaves on stone mortars. The plant yields a gluey mucoid substance that’s mixed with water and sprayed on the adobe, a technique Salvadorans have used for centuries to preserve their homes. The archeologists have found that spraying the adobe during the dry season helps keep the moisture level constant; the escobilla helps hold the clay together.

Salt is the other villain. When water evaporates from clay, it leaves a layer of salt on the surface, much the way sweating leaves one’s skin salty. But evaporation also leaves a salt residue just below the clay surface, and this is where the most damage occurs. When water evaporates, the salt crystals below the surface expand, forcing the clay minerals apart and causing more spalling.

To protect against damage from spalling, the escobilla solution is mixed with a small amount of clay, creating a repello sacrificial-- literally, a sacrificial skin. So now when spalling happens, says McKee, it’s the new material on top that we lose. (The new clay has a different look and texture, so archeologists can tell the original material from the protective layer.)

For dry, disintegrating materials, such as potsherds or bones, the artifacts conservation team at Cerén creates another form of protective skin. Harriet Beaubien and Ellen Rosenthal, both from the Conservation Analytical Laboratory, saturate the artifacts with a diluted solution of a resin called Acryloid B-72, which penetrates and strengthens the material. This method, however, is a technique of last resort. In general, conservators try to preserve artifacts without using additives. You never know if the synthetic additives are going to do acid damage, Beaubien explains.

But when it comes to storage materials, synthetic additives are a conservator’s salvation. Rosenthal holds up a piece of packing paper. It is so shot through with tiny holes that it looks like a player-piano score.

Bugs, says Beaubien. We’ve got insects that’ll eat the sizing off paper. We’ve got pack rats, mice, and termites that’ll motor through boxes in a matter of days. Forget about ‘acid-free,’ ‘cellulose-based,’ and ‘environmentally friendly.’ Give us spun-bonded, nylon-webbed. Give us Ziploc bags and chemically sound inks.

She holds up a Tupperware box, the edges of its lid whittled by tiny teeth. Then she points to a stack of plastic Continental Airlines snack boxes, each one holding a single artifact carefully placed in a polyethylene mount. These work better because the mice can’t sink their teeth into them. Payson sweet-talked a stewardess into giving him 80 of them. It’s a surreal sight, bones and scraps of fiber where you’re used to seeing ham sandwiches and cookies.

Sheets is sitting at his desk, a gray metal relic with conspicuously fewer drawer handles than drawers. His seersucker shirt, clean for this morning’s powwow with San Salvador bureaucrats, is sweated through and smeared with ash.

The sad irony of his work, he notes, is finding that the people of the region were living far better in A.D. 600 than they are today. Where the residents of Cerén constructed sophisticated buildings with wood- reinforced adobe and elevated roofs that allowed breezes to circulate, the peasants of contemporary El Salvador live in simple clay brick or cinder- block homes. Compared with the houses of Cerén, these homes are hot, inelegant, and unsafe in an earthquake. More people are crowded into smaller rooms, and they own fewer aesthetically pleasing possessions. They live mainly on corn and beans and rarely eat meat or fresh vegetables. Sheets is acutely aware of the contrast every time he visits the home of one of his workers or drives by the squatters’ camps that line the roads out of San Salvador. It’s impossible not to notice, he says. People are living in shacks of cardboard and scraps of plastic.

What keeps bringing him back to Cerén? He leans back in his chair. You want to know what makes it worthwhile? I’ll tell you a story. It was a Sunday in July 1993, the opening of the site museum. Bands were playing. The president was here. At one point I overheard a young girl and her grandmother standing at a photograph of one of the Cerén kitchens. The grandmother was saying, ‘That’s the kind of kitchen I was raised in, with an earth floor and open walls. . . . ’ That’s the really exciting thing-- the elements of continuity between the archeological past and the traditional Salvadoran household of today. But the country is modernizing so rapidly that those traditions are being lost. In doing cultural conservation, we are trying to give that past as good a future as we can.