On this typical sunny morning on this southeastern Florida beach, holidaymakers loll on their blankets and splash in the waves. Walking among them are two rather atypical beachcombers: Robert Higgins, 62 years old, dressed in a T-shirt and shorts and a floppy hat that covers his close- cropped hair; and Marie Wallace, a dark-eyed woman in her mid-forties in similar garb. They carry with them a shovel, buckets, plastic bottles, a fine-mesh screen, and a supply of freshwater--all the tools they’ll need for today’s scientific expedition.

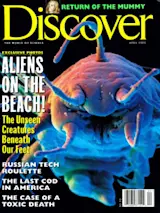

Although the other people on the beach are completely unaware of it, beneath their feet, in the seemingly sterile sand, there exists a microscopic jungle of surreal animals waiting to be discovered. Some of these minuscule invertebrates spend their lives slithering between the sand grains. Others flutter along by whirling hairlike propellers on their heads. Still others, as waves crash over them, hold tight ...