In late December, U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III offered a welcome and definitive ruling in the case against the Dover, Pennsylvania, school district: Intelligent design is not science and should not be presented in science classes as a viable alternative to evolution. As the judge put it, "The fact that a scientific theory cannot yet render an explanation on every point should not be used as a pretext to thrust an untestable alternative hypothesis grounded in religion into the science classroom or to misrepresent well-established scientific propositions."

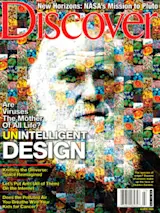

That conclusion is unlikely to surprise most readers of Discover. Nonetheless, the text of the ruling, an excerpt of which is available on Discover.com, is worth reading for its concise and eloquent description of scientific endeavor. The proponents of intelligent design have spun a campaign out of "teaching the controversy"—of using their largely hollow questions about evolution to wedge in their own "scientific" theory about life's origins. But as the Dover case and final ruling make clear, real science involves more than merely claiming that an idea you dislike is wrong: You have to demonstrate your case with evidence, and any alternative you float must also be open to testing and challenge. It's unfortunate that such a basic and widely accepted concept as evolution must be dragged into court for further validation. But in many ways the setting is apt, as the scientific notions of proof and evidence grew in part from 17th-century ideas in legal scholarship. Science and the law make the same case: Doubt is necessary, but alone it is not sufficient. Meanwhile, the scientific understanding of evolution—the particulars of it, if not the basic premise—continues to evolve. This month's cover story explores the implications of the discovery of the largest, weirdest virus in the world. Called Mimivirus, it contains more genetic material than any virus yet seen. Indeed, it shares so many traits with living cells that it blurs the usual distinctions between viruses and bacteria. Viruses are freaky enough already—parasitic clumps not fully alive that commandeer cells in order to replicate.

Scientists have assumed that viruses evolved long after the more complex bacteria and other organisms on which they depend. But Mimivirus has turned this thinking on its head: Perhaps the simple viruses we see today are mere shades of their former selves; perhaps Mimi is a relic of an early, grand epoch when viruses were genetically rich and ruled the Earth. Increasingly, many scientists believe that viruses evolved very early on, possibly even earlier than everything else. If so, they are not merely some ornamentation on the tree of life but rather may compose its very roots.

Now there's news for intelligent design's designers, and the rest of us, to ponder. We humans, and all life on Earth, may well have evolved from the most unintelligent entities one can imagine, genetic shards that do nothing but copy themselves. We are nobody's great idea; we are the fortunate mistakes of countless biochemical morons. That's evolution. It is humbling, but somehow comforting: Among its many products, evolution has produced a court of law in which the science of evolution is not treated mindlessly.