How well do we know ourselves? The fossil record of hominins, our ancestors and closest kin, is limited, and the exploration of our collective deep history through genetic analysis is still a relatively new field. Neither excavations nor lab work has been able to reconstruct, definitively, the earliest chapter of the Homo sapiensstory.

For decades, two competing models of human evolution have dominated the field. One claims that H. sapiensevolved in a single place, Africa, and left that continent only fairly recently; the other suggests that our species evolved in multiple regions across both Africa and Eurasia.

While debate between proponents of the two models rages on, there’s one big problem: Researchers keep finding fossil and genomic evidence that don’t fit either model.

A paleoanthropological review published in Science in December acknowledged that the evidence had reached a tipping point. It’s time, the authors said, for a new model of how our species evolved and spread across the world. But how does this new model compare with its predecessors?

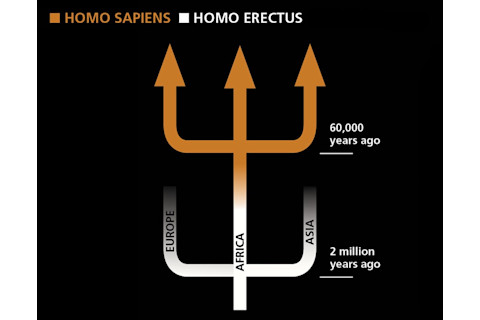

Recent Africa Origin Model

Dan Bishop/Discover

Beginning in the mid-20th century, fossils unearthed in Africa showed a progression, over millions of years, from a primitive bipedal primate to anatomically modern humans. Based on those fossils, researchers developed the Recent Africa Origin (RAO) model for human evolution and migration. According to the RAO model, although some groups of our predecessor Homo erectus left Africa roughly 2 million years ago, those early explorers eventually died out and did not contribute significantly to modern human ancestry. Instead, H. sapiens evolved exclusively in Africa and left the continent only about 60,000 years ago to spread across Eurasia. The RAO model has dominated Western thinking about human evolution for decades.

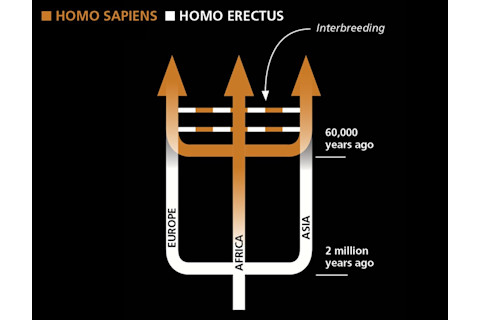

Multiregionalism Model

Dan Bishop/Discover

The RAO model does not account for some hominin fossils found outside of Africa, especially in China, that are 100,000 years or older but appear to belong to anatomically modern humans. Based on these fossils and some artifacts, a challenge to RAO emerged: multiregionalism. According to this model, after H. erectus populations left Africa roughly 2 million years ago, these intrepid hominins settled in pockets across Eurasia, where they continued to evolve into regional populations of H. sapiens. Multiregionalism agrees with one aspect of RAO: When the relative latecomer sapiens left Africa 60,000 years ago and met up with other hominin populations in Eurasia, some interbreeding occurred. According to multiregionalists, however, the ancestry of human populations outside of Africa, particularly in Asia, is rooted in the earlier regional H. erectus populations.

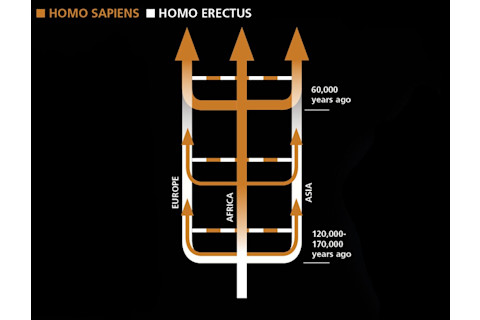

New Model

Dan Bishop/Discover

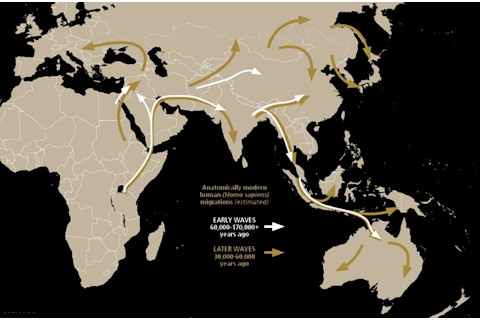

According to the new model proposed in the December review in Science, H. sapiens evolved in Africa but left the continent much earlier, about 120,000 years ago, and in multiple waves of migration. In January, the work of a separate team, also published in Science, pushed the start date for modern humans migrating out of Africa even farther back: Anatomically modern human fossils found in Israel were dated to more than 170,000 years old. While some of the early pioneers perished, others survived, reaching as far as Australia and East Asia. There, and along the way, migrating H. sapiens met and sometimes interbred with other hominins, including Neanderthals in Europe and Denisovans in Asia, as well as, potentially, other populations not yet known to science. The new and more complex model doesn’t just reflect the latest research — it also emphasizes the interconnectedness of our entire species and our closest kin.

Dan Bishop/Discover and Ekler/Shutterstock