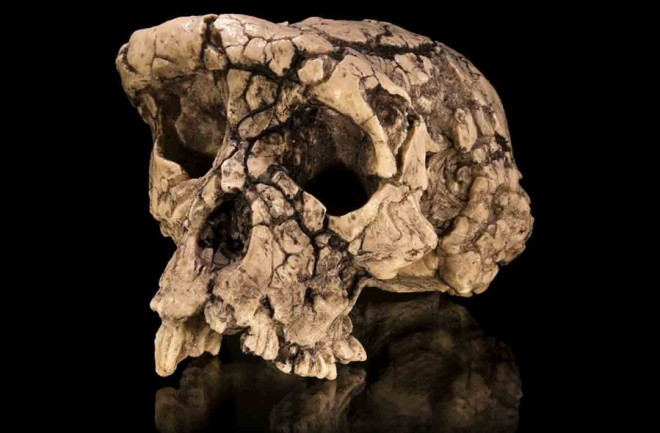

The partial skull and jaw fragments of Sahelanthropus tchadensis are the earliest hominin finds known. (Credit: Didier Descouens/Creative Commons 4.0) Roughly 8 million years ago, some apes stood up and started human evolution. Okay, that’s not really what happened. But it is a fair characterization of the way scientists identify the oldest fossils likely to be human ancestors. Upright walking apes mark the start of the study of human evolution in many texts and classes. That’s because bipedalism, or two-legged locomotion, was the first major evolutionary change in human ancestors, which is evident from bones. Other distinguishing features, like big brains, small molars and handcrafted stone tools, came millions of years later. Therefore, to find early members of our lineage, anthropologists look for ancient apes with skeletal traits indicative of habitual bipedalism — they regularly walked upright. So who were the first bipedal apes and would you recognize them as relatives?

Hominins and Panins Part Ways

Homo sapiens and our closest living relatives, chimpanzees (Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes), both descend from the same stock of African apes. Researchers often call this creature the last common ancestor or LCA (go back far enough and you’ll have an LCA with every organism on earth, but when anthropologists say “LCA” they’re usually referring to the chimp-human one). Sometime between 6 and 9 million years ago that population split into two lineages — one eventually leading to chimps and the other leading to humans. Hominins are any living or extinct species along the human branch after the LCA. So-called "panins" are any species along the chimp branch after the LCA.