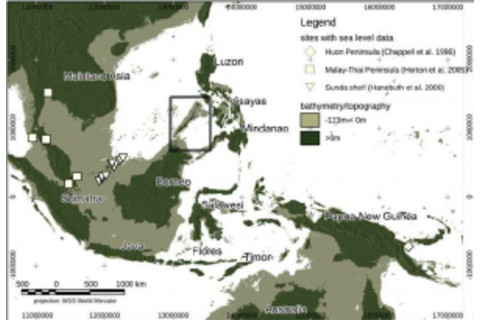

Researchers say cut and percussion marks on a rhino suggest a hominin presence in the Philippines more than 700,000 years ago, ten times earlier than previously known. (Credit Ignicco et al 2018, 10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8) More than 700,000 years ago, in what's now the north end of the Philippines, a hominin (or a whole bunch of them) butchered a rhino, systematically cracking open its bones to access the nutritious marrow within, according to a new study. There's just one problem: The find is more than ten times older than any human fossil recovered from the islands, and our species hadn't even evolved that early. Okay, so, maybe it was an archaic hominin, you're thinking, maybe Homo erectus or some other now-extinct species. But there's a problem with that line of thought, too. According to the conventional view in paleoanthropology, only our species, Homo sapiens, had the cognitive capacity to construct watercraft. And to reach the island where the rhino was found, well, like Chief Brody says, "you're gonna need a bigger boat." So who sucked the marrow from the poor dead rhino's bones? It's a whodunit with the final chapter yet to be written. A single foot bone that's about 67,000 years old is currently the oldest human fossil found in the Philippines (fun fact: the bone was found in Callao Cave, not far from Kalinga, the site of today's discovery). For more than half a century, however, some paleoanthropologists have hypothesized that hominins reached the archipelago much earlier. The pro-early presence camp has cited stone tools and animal remains originally excavated separately in the mid-20th century, but critics have noted there's no direct association between the tools and bones, and the finds have lacked robust dating. The larger obstacle in the eyes of the anti-early presence camp is all wet. At numerous times in our recent history, geologically speaking, falling sea levels have exposed land surfaces now underwater, connecting islands and even continents to each other. The land bridge of Beringia is perhaps the most famous, joining what's now Alaska with Russia at several points in time. Land bridges were a thing in the broad span of geography between China, Southeast Asia and Australia, too.

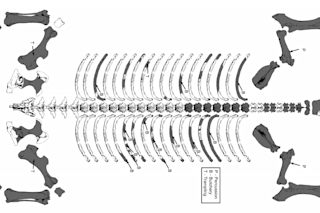

An example of how much land can be exposed during periods of sea level drop. A team of researchers not involved in today's study created this map in 2015 as a paleogeographical reconstruction of Palawan Island, in the Philippines. The site mentioned in the new research is from the northern part of Luzon, top center of the map. (Credit Robles, Emil, et al. "Late Quaternary sea-level changes and the palaeohistory of Palawan Island, Philippines." The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 10.1 (2015): 76-96.) These lost land bridges made it possible for animals — including humans and other members of our hominin family — to expand into places that are now island nations, such as Indonesia. But although the Philippine archipelago once had more real estate, several of its islands were never joined to the mainland. And that's where today's mystery begins. Stones and Bones Researchers working at a site in the northern part of the island of Luzon report the discovery of 57 stone tools found with more than 400 animal bones, including the mostly-complete remains of a rhino (the now-extinct Rhinoceros philippinensis, a poorly known subspecies... having a specimen that's about 75 percent complete is an achievement in and of itself). Using the electron-spin resonance method on its tooth enamel, the team established that the rhino was about 709,000 years old. Thirteen of its bones, according to the study's authors, showed signs of butchering, including cuts and "percussion marks" on both humeri (forelimb bones), which is typical of smashing open a bone to access the marrow. Alas, none of the bones found belonged to a hominin, which not only could have told us the butcher's identity but also confirmed that butchering took place. If you're thinking it sounds kind of familiar to read a Dead Things post about apparent stone tools beside an animal that appears to have been butchered at a time and place out of sync with the human evolution timeline, well, you're not wrong. You may recall, about a year ago, the not-insignificant hullabaloo that erupted over claims that a hominin had processed a mastodon carcass in what's now Southern California 130,000 years ago — more than 110,000 years before humans arrived on the continent, according to the conventional timeline. The skeptical pushback about the Californian find continues, most recently in February in Nature, and the claim is unlikely to be taken seriously unless a hominin fossil turns up. Today's discovery at Kalinga is in many ways just as convention-busting, though the tools at the site appear more obviously shaped by a hominin than those at the California site. Let's accept that Kalinga is indeed a butchering site, where at least one hominin processed the carcass of at least one animal. Then the question becomes: which hominin? The Unusual Suspects There is no evidence that H. sapiens is anywhere close to 700,000-plus years old. Although researchers are pushing back the timeline for our species' emergence, even the most out-there genetic modeling places the dawn of our species at no more than 600,000 or so years. What's more, the oldest fossils classified as H. sapiens, from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, are about 300,000 years old, and even calling them H. sapiens has been contentious. Although the face appears strikingly modern, the lower, more elongated shape of the Jebel Irhoud hominin brain case suggests that the individuals had a smaller cerebellum, lacking the advanced cognitive skills of modern humans. In fact, only anatomically modern humans like you and me have ever scampered about boasting such big, fancy brains, with an oversized cerebellum that makes us stand out in a hominin lineup. Because the cerebellum is linked to creativity and fine motor skills, among many other functions, the fact that Neanderthals and other hominins had smaller versions is one of the reasons many researchers believe only H. sapiens has been capable of complex processes...processes such as building a boat and getting it across water from Point A to Point B. It's reasonable to rule out H. sapiens at Kalinga, as well as Neanderthals and Denisovans, who also had not yet evolved. But that leaves only archaic hominins, such as H. erectus or another as yet unknown member of our family tree, able to boat across open water to Luzon. We won't know for sure who enjoyed a snack of rhino marrow some 709,000 years ago until we find their bones. The findings were published today in Nature.