Snakes, with their sleek, slithering shape, are unmistakable amongst the reptiles. Yet for decades, scientists have been debating just how these limbless lizard relatives ended up with their distinctive, elongated body.

On one side are scientists who argue that the serpentine shape was an aquatic adaptation. Many snake traits, including an elongated body and reduced limbs, are also features of swimming animals (think whales and dolphins, for example, which have lost their hind limbs). Early evidence also suggested that snakes were closely related to mosasaurs, the terrifying and extinct group of lizards that were woven into pop culture the moment one was fed a great white shark in Jurassic World. Non-theatrically, these marine reptiles ruled the seas during the Cretaceous, and possessed many snake-y features, including a jaw which stretches for large prey. The discovery of extinct marine snakes with hindlimbs, including Pachyrhachis, Haasiophis, and Eupodophis, seemed further proof of a marine origin.

But later analyses have suggested that Pachyrhachis and others are secondarily marine, the offshoots of a more derived snake group, and the connection between snakes and mosasaurs has come under suspicion. The prevailing hypothesis is now that snakes evolved on land — or, even more specifically, in it. A burrowing or ‘fossorial’ lifestyle could also produce long, skinny bodies and reduced limbs. More recent finds like Najash, Dinilysia, and Coniophis, which date back further than Pachyrhachis, all lived on land. But the evidence for a largely underground existence isn’t conclusive, either, and some hold to the idea that snakes were born in the sea.

The debate has continued so long because there is a dearth of snake fossils to rely upon. Snake bodies are by and large small and fragile, with thin bones that do not lend easily to fossilization. So scientists have had little material to work with when trying to determine changes over time.

A new fossil hopes to end the debate once and for all. A paper published this week in Science describes what appears to be a four-legged burrowing snake from Brazil. “Here it is, an animal that is almost a snake” says David Martill, a paleobiologist from the University of Portsmouth, “and it doesn’t show any adaptations to being in an aquatic environment.” But is it really that cut-and-dry? While the latest fossil find is making a splash in the news, it’s one of four noteworthy papers this year examining snake evolution, and placing the new study in context helps explain what makes the fossil so exciting, if controversial.

Reconstructing Snake Relationships

Some would argue that the origin of snakes was pretty much settled back in May, when a landmark paper by Allison Hsiang and her colleagues was published in BMC Evolutionary Biology. “We put together a large dataset comprising both fossil and living snakes and used mathematical models and computer programs to infer ‘ancestral states,'” explains Hsiang, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at Yale University. The diagram of snake evolutionary relationships they produced, called a phylogenetic tree, is the most robust analysis of snake evolution to date, and it strongly supported the land-based evolution of serpents.

Ancestral state analyses, which essentially use math and science to estimate the biological and ecological traits of the most recent common ancestor of a group of species, suggested that early snakes were nocturnal hunters, preying upon the small vertebrates of their era through stealth, not constriction. Their analysis didn’t find that snakes were burrowers, however — there was no strong support of a fossorial lifestyle, just that the snakes lived on land.

According to Hsiang, morphological data “strongly influenced” the snake tree. “Our study helped to demonstrate how important and essential it is to include fossils when we are trying to understand how and when organisms evolved.” In the paper, the authors note that the inclusion of fossil data resulted in relationships that would be “unexpected” given current snakes, and that the fossils’ influence was sustained “even when such data are vastly outnumbered by genetic sequence data,” thus including the new fossil in a similar analysis might be even more informative.

“Now that Martill et al.’s paper on Tetrapodophis has been published, the obvious next step is to include it in large-scale, comprehensive analytical studies looking at snake evolutionary history and phylogenies.”

In The Beginning?

Though there was some excitement when Hsiang and her colleagues published their analysis in May, a paper published a little over a month earlier in PLoS ONE slipped by the press unnoticed. The analysis, led by Tod Reeder from San Diego State University, looked beyond snakes to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships within the squamates, the group of reptiles that contains lizards and snakes. Using the largest dataset to date which, like Hsiang, included both genetic and morphological markers, Reeder and his colleagues affirmed one of the crucial pieces of evidence of a marine snake origin: the close relationship between mosasaurs and snakes.

“The most comprehensive analysis of the lizard evolutionary tree now reinstates these aquatic mosasaurs as the nearest relatives to snakes,” explains Michael Lee, associate professor at the University of Adelaide, who was one of the first scientists to suggest that snakes may have started in the water.

Because of this, Reeder et al. calls into question the methods used by Hsiang et al., specifically one of the core assumptions in the paper: the closest relatives of snakes. When constructing evolutionary trees, assumptions have to be made to “root” the tree, or put the relationships into the context with regards to time. Scientists must compare their data to what is called an “outgroup”, which is ideally the closest relative or relatives to the group of interest. Hsiang and her colleagues used a subset of a group of lizards called anguimorphs, which includes land dwelling lizards like the Komodo dragon.

“The Hsiang paper was a terrific analysis of the evolution within snakes, but the fundamental core assumption they made in the paper was that terrestrial lizards were ancestral to snakes,” said Lee. “The direction of evolution was determined by that assumption. But if you assume, as the Reeder paper suggests, that mosasaurs are ancestral to snakes, then some of the inferences by Hsiang might not hold.”

Hsiang admits that there are differences between the phylogenies in her paper and Reeder’s, and that the choice of outgroup may have skewed their results. “There are differences between the Reeder et al. phylogeny and our phylogeny — it would be interesting to conduct an in-depth analysis to try and determine why the differences in phylogeny exist,” she said. While her team’s tree was strongly influenced by morphology, Reeder’s team found that genetics most strongly predicted the results. “In fact, the morphological data are really ambiguous,” co-author John Wiens said in a press release. “Or in some cases, even worse than ambiguous.”

“There’s certainly a possibility that our results would have been different if we had used different outgroups, as phylogenetic and ancestral state reconstruction analyses use the outgroup to determine the direction and polarity of character state evolution,” said Hsiang. However, she doubts the impact would have been large, as other close relatives of mosasaurs are land-lubbers. “Though the inclusion of mosasaurs would likely have increased the probability of an aquatic lifestyle for early snakes somewhat, this would probably have been “balanced out” by the many anguimorph lizards that are not aquatic.”

“Of course, we’d have to actually run the analysis to know for sure.”

Seeing Through The Bones

Meanwhile, Bruno Simões from the Natural History Museum, London, UK and his colleagues were taking a very different approach to understanding snake evolution. Instead of looking at bones and unrelated genes, they very specifically examined the genes encoding for visual pigments in lizards and snakes. These genes are well-studied, and in other groups like mammals, are correlated with behaviors like burrowing and nocturnal activity.

“Visual pigments, like opsin and rhodopsin, are basically the business front-ends of the visual pathway,” says Simões. “So basically if anything is happening in the visual system, the visual pigments will be the first to be impacted.” Burrowing mammals, for example, have lost some visual pigment genes, as they no longer need them underground. But even more impressively, scientists can connect genetic changes in these pigment genes to ecology and function. “By checking their amino acid composition, you can estimate what kind of wavelengths the animal can see,” says Simões.

When Simões et al. compared the visual pigment genes in snakes to other lizards, they found something exciting: snakes have lost two of the five pigments found in the rest of the squamates. They retain the same three that we have. Simões explained that this means snakes likely went through an “ancestral nocturnal bottleneck,” just like mammals did. “Snakes have this contrasting pattern from lizards that converges with mammals.”

Interestingly, in fossorial lizards, all five pigments were still around, but in fossorial snakes like the termite-decapitating blindsnakes, only one pigment remained. “The fact that the visual system was not so reduced suggests that the ancestor for all snakes was nocturnal, not fossorial” — a finding which coincides with the ancestral state reconstructions found by Hsiang et al.

As for the question of marine origins, Simões says that he “didn’t find evidence that it was a marine animal.” Marine environments have very different light conditions than terrestrial ones, with a quick loss of red wavelengths with depth, followed by an eventual loss of all light in the deep sea. Marine animals eyes often show a “shift in spectral tuning to a marine environment,” says Simões, which includes a higher sensitivity for blue wavelengths. In sea snakes, for example, the shorter-length opsin 1 becomes blue sensitive instead of UV sensitive. But Simões found no such shift in all snakes.

“I think that it’s a really interesting paper, in that they’ve discovered that snakes have lost a whole bunch of visual genes that are found in other lizards, which does suggest they went through some kind of semi-blind phase in their evolution,” says Lee. But he still would like to see more research before discounting the aquatic hypothesis. “One thing I’d like to see done is what genes are lost in living marine reptiles like sea turtles,” said Lee, to see if there are any opsin genes lost in other marine reptiles like the ones lost in snakes.

A Four-Legged Snake?

Which brings us back to the most recent finding, what Martill and his colleagues claim is a four-legged snake ancestor from Brazil. Though there’s no concrete information about where this fossil originated, the color and texture of the limestone it is encased in suggests it’s from the Crato Formation, a fossil deposit which was laid down some 100 million years ago when the area was a shallow sea.

“The Crato formation is about 20 million years older than the oldest fossil snake,” Martill explained. Thus this ten centimeter-long fossil, which Martill and his colleagues named Tetrapodophis amplectus, may shed light on the earliest snakes.

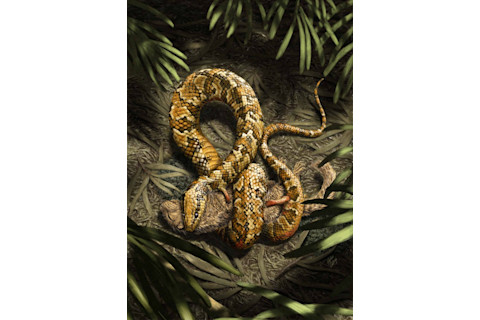

Artist Julius T. Cstonyi’s recreation of Tetrapodophis amplectus subduing its mammal prey in an early Cretaceous tropical forest in Gondwana. (Credit: Image provided by Science)

Image provided by Science

“The Martill paper is going to be one of the most controversial papers around for a long time,” said Lee. “I’ve already had about 50 emails from colleagues about it, all expressing really different views.”

“It is a very unusual specimen,” Lee said, “because if it is a snake, it’s a tremendous missing link between lizards and snakes.”

But there are several lineages of lizards with lost or reduced limbs and longer bodies, so the evidence to place it as a snake ancestor must be more than just that. Martill notes that the short length of the tail in relation to the body, structure of the pelvis, impressions of body scales, recurved teeth, high vertebral count and the shape of the vertebrae all make Tetrapodophis a snake. “This thing is much much more of a snake than it is of a lizard,” he concluded. But some scientists don’t buy it. “I think the specimen is important, but I do not know what it is,” University of Alberta paleontologist Michael Caldwell told Ed Yong from National Geographic. But Lee is willing to give Martill the benefit of the doubt. “I’m prepared to provisionally accept that it’s a very unusual small snake,” he said. “But the specimen is so small and the skull is so badly crushed that I think there is going to be a lot of debate until all interested researchers are able to look at it.”

“It does seem to have some pretty intriguing snake features,” Lee admits. “Snake teeth have a very distinct curvature to them… and this animal does seem to have that. So that’s one feature that really makes me think this is probably a snake.” He’s also impressed by the animal’s spine. “It’s got a very large number of vertebrae — 160 backbone elements — which is also a very snake-like feature,” he added. “None of the other features that they list do I find particularly compelling.”

Hsiang, on the other hand, is entirely convinced. “Tetrapodophis does seem to possess many anatomical features that are unique to snakes — the recurved teeth, intramandibular joint, vertebral characters, et cetera,” she said. “So, based on Martill et al.’s report of the anatomy, it seems likely that Tetrapodophis is indeed an early snake.” She’s especially intrigued by what else is visible in the new fossil: its last meal. Martill et al. report that inside the snake’s stomach are a collection of vertebral bones, likely from a small mammal or lizard that it ate just before it died — the same diet that Hsiang et al. predicted with their ancestral state analyses. “The new fossil provides empirical confirmation of some of our results,” she noted. “For instance, the discovery of vertebrate bones in the stomach contents of Tetrapodophis aligns with our inference that the earliest snakes likely ate small vertebrates.”

According to Martill et al., the short tail and reduced limbs are evidence that Tetrapodophis was a burrowing snake. “Although this thing has been found in sediments that were laid down in water,” Martill says, “the shortened limbs and the little scoop-like feet that it’s got on its hind limbs look much more like they’re for burrowing than they are for swimming.”

“Also, they wouldn’t really function for swimming,” Martill said. “This thing is almost certainly using lateral undulatory locomotion to burrow through soft sand and leaf litter.”

“I think that’s fairly weak evidence,” said Lee. “There’s no living burrowing lizard or snake with those type of body proportions,” he added. “We can’t really say what it did at the moment, because there are too many contradictory traits in this animal.”

Scoops or paddles? Or something else entirely? (Credit: Dave Martill, University of Portsmouth)

Dave Martill, University of Portsmouth

Lee similarly points to the shape and size of the limbs and feet, but says they provide evidence of an aquatic lifestyle rather than a fossorial one. Species known for their burrowing habits, like moles, have short, squat, strong limb bones, but Tetrapodophis has “long, delicate fingers and toes.” There are also questions about the composition of the bones themselves; bones can vary in the amount of calcium they contain, with more calcium or “more ossified” bones resisting breakage better than less ossified ones. Lee notes that the limbs of Tetrapodophis seem to be “fairly poorly ossified.” “That’s not what you find in burrowers because you want your hands and feet to be as robust as possible to push through the soil.” Reduced ossification of limb bones is, however, a trait shared by other aquatic organisms. Furthermore, in the hind feet, two ankle bones that are fused in most lizards are separate. The only other group of lizards where these bones are apart? The aquatic mosasaurs. Rather than seeing the feet as scoop-like, Lee sees them as “paddle-like.” He also noted that the bones of the fingers and toes are perfectly aligned in parallel with one another. “That leads me to think that they were held together in something, like a flipper or sheath.”

All of that and the fact that the animal was found in what, at the time, was a shallow sea, does give credence to the idea that it could be an aquatic snake. “I wouldn’t come out and say that it’s aquatic, because I don’t think we can say that either,” Lee said, “but I don’t think that we can conclude that it’s burrowing.”

“The aquatic idea of snake origins might be the minority view, but there’s enough accumulating evidence now that it needs to be reexamined rather than dismissed out of hand.”

Brazil’s Big Discovery … In Germany?

Though Tetrapodophis is perhaps the most scientifically-intriguing snake fossil to date, questions about how it arrived in Germany are already beginning to overshadow its scientific importance. Even before the paper officially published, rumors swirled about whether the remarkable specimen was illegally poached from Brazil. When I asked Martill about the specimen’s discovery, he was disturbingly cavalier about the fossil’s origins. “More or less, I discovered it,” he said, “I actually found it in a museum collection.”

“It was one of those serendipitous things,” he continued. “I actually worked on fossils from this location in Brazil for many many years.” But Martill didn’t find Tetrapodophis on an excursion to the jungle; he found it labeled as an “Unknown Fossil” in the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum in Solnhofen, Germany on a routine class trip for his students. It just so happened that when he took his students to see the museum, on display was an exhibit on Brazilian fossils, which Martill — having written a book about the Crato formation — was excited to see. “All of a sudden, my jaw just dropped to the floor,” he recounts. “This looks like a snake!”

When pressed, he admitted that there was no information about the fossil’s origins — when it was found, who pulled it from the earth, and how or why it made its way across the ocean to a small museum in Germany. He was more blunt when he spoke to Herton Escobar (quoted by Sid Perkins for Science). Martill told him that questions about legality are ‘irrelevant to the fossil’s scientific significance’ and said: “Personally I don’t care a damn how the fossil came from Brazil or when.”

As Shaena Montanari explains for Forbes, given the laws in Brazil since 1942, it’s likely that Tetrapodophis found its way to Europe illegally. Brazililan officials have gone as far as to say they’re certain the specimen illegally left the country. Many scientists are expressing their outrage that a prestigious journal like Science would even publish a paper based upon what is likely a black market specimen.

.@sciencemagazine Sirs, isn't it against the journal policy to publish a paper based on a *illegal* fossil?

— Roberto Tanaka (@rmtanaka), July 23, 2015

I'm appalled the author of that 4-legged snake study doesn't "give one damn" about how the fossil came out of Brazil (legally or illegally).

— Dr. Jacquelyn Gill (@JacquelynGill), July 24, 2015

Anti-community? Yes. This is stealing. That's what this is. The fossil was potentially illegally collected and sold, and illegally exported.

— Sarah Werning (@sarahwerning) July 24, 2015

Martill has expressed his bullish attitude towards Brazilian fossils & the laws meant to protect them before: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Geoscientist/Archive/November-2011/Protect-and-die

.@diapophysis It's a distinctly colonial attitude—the locals don't know what they're doing so let's ignore their rules and do what we want.

— Jeff Wilson Mantilla (@diapophysis) July 23, 2015

what bothers me most about #fossilsnakegate is that the fossil would still be just as spectacular if it was repatriated to Brazil.

— J. Pardo (@incisorial) July 23, 2015

This isn’t the first time Martill has expressed a lack of concern over fossil provenance, as some have noted, and his current comments reveal a deeper pattern of neglect or contempt for other countries and cultures that is, quite frankly, repulsive. Tetrapodophis rightfully belongs to Brazil — it should be displayed in a Brazilian museum, providing income and excitement for Brazilians. And I find it very unsettling that Science would publish a paper on a specimen that it couldn’t provide provenance for. It strikes me as lazy science at best to make claims about a fossil’s origins and its implications for the evolution of a lineage without solid evidence of when and where it came from.

I hope that Martill reconsiders his position on this, and makes an effort to return the specimen to where it belongs.

Citations:

Martill, Tischlinger & Longrich. (2015). A four-legged snake from the Early Cretaceous of Gondwana. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9208

Hsiang et al. (2015). The origin of snakes: revealing the ecology, behavior, and evolutionary history of early snakes using genomics, phenomics, and the fossil record. BMC evolutionary biology, 15(1), 87. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0358-5

Reeder et al. (2015) Integrated Analyses Resolve Conflicts over Squamate Reptile Phylogeny and Reveal Unexpected Placements for Fossil Taxa. PLoSONE 10(3): e0118199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118199

Simões et al. (2015). Visual system evolution and the nature of the ancestral snake. Journal of evolutionary biology 28(7): 1309-1320. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12663

Update: Corrected, as quote about not caring was said to Herton Escobar, not Sid Perkins. Read the full interview between Martill and Escobar here.