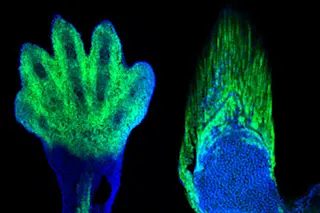

The same group of cells (highlighted in green) is responsible for creating digits in mice (left) and fin rays in fish (right). (Credit: Shubin Laboratory) Millions of years ago our ocean-dwelling ancestors stepped forth onto new shores and began populating Earth's dry land. Fossils such as Tiktaalik, one of the most compelling members of the class of transitional "lobe-finned fishes", mark the evolutionary path that led to land-bound animals. The transition from delicate fins to sturdy limbs didn't happen all at once, but it is clear that our appendages are distant cousins of fish fins. Using cutting-edge DNA mapping techniques, researchers from the University of Chicago have discovered fins and fingers emerge from the same group of embryonic cells, shedding light on how our earliest ancestors made landfall.

They focused their study on Hox genes, which are known to influence the body plan of an embryo. A subset of these ...