“Find out where all the short-legged dogs come from,” an acquaintance told me, just before I left for Rarotonga, the capital island of the Cook Islands. Given that I was going to work as a veterinarian and that I had volunteered to collect DNA samples for the canine genome project, the request didn’t come entirely out of left field. Still, it seemed like some sort of inside joke.

Once I arrived, everything began to make sense. There are a lot of dogs on the island, most of them reminiscent of dingoes, like feral dogs the world over. But a good third of them have legs almost as short as a dachshund’s—though straight and lovely rather than crooked like those of most dwarf breeds. I guessed that these short-legged dogs descended from some distant European ancestor, some basset hound on holiday. But that thought only proved how little I knew about the origins of dogs and other domesticated animals.

Short legs, it turns out, aren’t that rare. The characteristic may even be a function of domestication. Animals don’t just become tame when they adapt to human society. They often become smaller, spotted, pug-nosed, floppy eared, oversexed, and small brained. They do this no matter what the species, genus, or taxon—dog, cat, cow, horse, sheep, pig. When natural selection narrows its focus on a single trait—docility—a suite of other traits tumble along behind. And those traits offer insight into biological development.

“Not one of our domestic animals can be named which has not in some country drooping ears,” Charles Darwin noted in The Origin of Species. His theory of natural selection was based in part on what he observed in domesticated species. Now genes dominate evolutionary theory, but some scientists argue that geneticists are missing something: DNA sequences alone can’t explain the many forms that species take. By looking closely at domesticated animals, they say, we may be able to unlock the mystery of how genotypes give rise to phenotypes—how nearly identical stretches of DNA can create radically different dogs.

The dogs of Rarotonga live in a state of pleasant anarchy. They wear no leashes, and few are collared. They are not so much owned by individuals as by everyone. Anthropologists call such arrangements community domestication. Some dogs are fed; many forage on coconuts, fruit, and garbage. Walk to the beach and you will accumulate dogs, gamboling with one another and with you. Once at the beach, they sit by your towel or wander into the shallow lagoon to fish. They wade out, noses pointed toward the water. If a fish comes by, a dog will pounce with both forefeet. Then it will carry the catch back to the beach and eat.

They are nice dogs and easy to work with, and they became my scientific subjects calmly and gracefully. The canine genome project is a multinational collaboration similar to the Human Genome Project. The DNA samples I was collecting were for Marcia Eggleston’s veterinary genetics lab at the University of California at Davis. Eggleston’s part of the project was aimed at finding genetic markers that would help biologists zero in on the genes that cause defects in purebred dogs, such as hip dysplasia and epilepsy. Other labs could then compare DNA sequences from purebred dogs; wild canids such as wolves, coyotes, and dingoes; and feral dogs. Most inherited diseases are associated with inbreeding, so the diseases don’t exist in wild canids and should be less common in feral dogs. By comparing their genes, biologists hope to identify and map defective sequences.

Eggleston’s lab had a good deal of purebred dog DNA and just enough wild canid DNA. But her only samples of feral dog DNA were from Bali and South Africa, where veterinarians had taken samples while spaying and neutering street dogs. Now I would do the same in the Cook Islands.

At my clinic, the cages were always full: We desexed dogs and cats and treated animals poisoned by fish, hit by cars, or made ill by intestinal parasites. (Our services were free, but we ended up with a lot of fruit and coconuts.) The DNA sampling involved no more than twirling a cytology brush, which looks like a miniature test-tube brush, between a dog’s cheek and gum. Afterward, each subject sat for a digital portrait. I labeled samples with dog names and Zip disks with pictures and shipped everything back to the States.

Word got out of my interest. Rarotonga is like a small town, and each new veterinarian at the clinic is profiled in the local paper. The islanders found it amusing that their dogs were the objects of scientific scrutiny. A few brought their animals in just for the sampling. Cook Islanders have a dry sense of humor and like to flaunt cultural differences to provoke reactions. One fellow at first refused to let me spay his dog, for if all the dogs were desexed, where would the islanders get more dogs? And if there were no more dogs, what would he eat?

I had been working on the island for two weeks when I received the phone call that revamped my worldview. Gerald McCormack, Rarotonga’s national naturalist, author of the local nature guidebook, and director of the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project, wanted to know the results of the canine DNA analysis. What did they show about the origins of the short-legged dogs? My answer was sketchy at best, so I tried to mollify him by saying that they were probably all descendants of some European import. “Quite possibly not,” he said. “Read Cook’s journals.”

Captain James Cook was the first European to visit many of the islands of the South Pacific. But when he sailed by Rarotonga sometime between 1773 and 1779, the island was far from pristine. Polynesian and Maori peoples had colonized it almost a thousand years before, bringing animals, including rats and dogs, either intentionally or as stowaways. Today rats are the most widespread mammals: Anthropologist Lisa Matisoo-Smith of the University of Auckland in New Zealand has used rat gene sequences to trace human migrations. Dogs come in a close second.

Cook didn’t have much to say about dogs in his journals, but his naturalist, George Forster, did. Forster wrote that many dogs on the islands looked like dingoes but were often spotted. Some of them were also short legged, or “very low on the legs,” as he put it. Sketches from that time show dogs that look very much like the dogs I treated. They were called poe dogs or poi dogs and were often meant for the dinner pot.

Belyaev bred his animals for docility alone. He began by selecting foxes that would not run too far away when approached. Then he upped the ante, picking foxes that would allow themselves to be touched. To prevent inbreeding, he continually brought in docile foxes from other farms. Considering how long it took for dogs to be domesticated—the oldest doglike skeletal remains were found in central Russia and date to 15,000 years ago, perhaps a million years after the first wolves appeared—the foxes settled down quickly. After 43 years and more than 35 generations, involving some 45,000 animals, the farm now has foxes that will follow people around, whining and barking for attention. They will lick faces, wag their tails, and eat from their keepers’ hands. Tests have shown that they produce lower levels of stress hormones, like adrenaline and cortisone, and have small adrenal glands. Their brains have higher levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter believed to influence emotion.

But that isn’t all. When Belyaev began, his foxes had thick, silvery coats. Forty years later, they were spotted or collared like border collies; they had curled-up tails, floppy ears, and two reproductive cycles a year instead of one. Some of the foxes were born with stars on their foreheads—a marking common in domestic animals like horses but rare in the wild.

Belyaev tried to explain the star markings by postulating a star gene. He related it to the production of dopa, a molecular precursor of adrenaline and dopamine, which are involved in an animal’s reaction to stress. Dopa is also a precursor for melanin, the molecule that pigments skin and fur. Belyaev suggested that sometime during embryonic development the production of dopa was delayed, creating docile foxes with patches of white fur and skin.

Then Belyaev carried his hypothesis further. He said his foxes, like all domestic animals, were in something like a state of arrested adolescence. Theirs was an evolutionary shortcut, he thought, a “destabilizing selection” that allowed them to adapt to intense selection pressures. By ratcheting down development, they became “hopeful monsters”—half-formed species that could remodel themselves to suit a rapidly changing environment. They weren’t just accidental mutations, Belyaev believed; they were experiments in adaptation.

Belyaev died in the 1980s, leaving his foxes with geneticist Lyudmila Trut. She has continued the work, but because funding was disrupted by the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has been a struggle. The foxes are friendly enough now that Trut thinks they’d make good pets. And there is something else, she says: Very rarely, the foxes have short legs.

Belyaev had a “novel” perspective on genetics, says evolutionary biologist Robert Wayne at the University of California at Los Angeles. “He was writing in a time before the molecular revolution, before we had much idea of how genes react with one another and the actual molecular basis of changes in genes and their regulation.” But for other scientists, the story doesn’t stop there. At Colorado State University, for instance, animal scientist Temple Grandin has studied hair whorls on the foreheads of horses and cattle. “Horse trainers for a lot of years have looked at them and suspected a relationship to temperament,” she says. “But a lot of other people have responded by saying, ‘Oh, that’s just nonsense.’ ”

Grandin decided to put the trainers’ intuition to the test. She watched cattle run through a squeeze chute, noting their behavior and the placement of their hair whorls. Sure enough, there was a correlation. “The higher the whorl, the more likely the cow was to fight the chute, to jump about and go berserk,” she says. “The lower the whorl, the more likely the cow was to just stand still.” This is more than an interesting bit of trivia, Grandin insists. In the embryo, hair whorls develop at the same time as the nervous system. And in people, unusual hair whorls at the crown of the head can be correlated with developmental defects like Down syndrome. There is a high prevalence of counterclockwise whorls in schizophrenics.

SHY LIKE A FOX

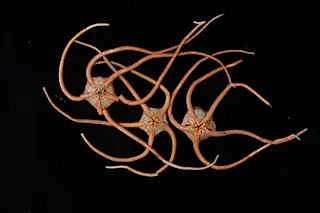

Dogs are the oldest and most studied domestic species, yet no one knows exactly how they took their present form. Although they descend from wolves, they rarely look like wolves, and most of those that do are no more similar to wolves genetically than those that don’t.

Some of the best evidence about the evolutionary origins of dogs comes, ironically, from studies of foxes. In 1959, Russian geneticist Dmitry Belyaev took a colony of wild foxes from a fur farm (top) and began selecting them for docility. After only 20 generations or so, he had piebald, droopy-eared animals (bottom) that were not so different from border collies. Belyaev believed these changes were experiments in adaptation: The foxes were remodeling themselves in order to survive in an intensely changing environment.

Archaeological digs suggest that dogs and people began to live together some 10,000 to 14,000 years ago. But recent mitochondrial DNA sequencing by Robert Wayne of UCLA and Carlos Vilà of Uppsala University in Sweden has pushed the relationship back another 90,000 years. The first dogs may not have been man’s best friend exactly, but they were closer to them than to wolves.

Some researchers suggest that the first archetypal dogs looked like Australian dingoes, Indian pariah dogs, and other modern, semidomesticated dogs. Others believe the earliest dogs looked like the feral dogs of today and that if modern dogs were allowed to interbreed they would revert to that type. Research on street dogs in Bali seems to support this: Their DNA is more diverse than that of any other group of wild or domestic canines yet studied.

Did feral dogs give rise to all the dog species in the world, or did all those dogs just contribute their DNA to the feral gene pool? Hard to say: The Balinese dogs don’t seem to have especially ancient DNA sequences, and dingoes and pariah dogs have had their gene pools watered down by interbreeding.

—C. M.

Grandin sees thousands of animals every year, all over the world. Again and again, she has seen links between temperament and body type. For example, in recent years, as breeders have focused on producing leaner meat, they’ve created slender, longer-legged cattle and pigs. The animals seem to be flightier, she says. “They’re much more nervous and have a much bigger startle response than the fatter, heavier-boned kinds if you tap them on the butt.” The pigs are so fretful in captivity they have developed serious behavior problems; they chew each other’s tails off. “It is as if we are breeding the wildness back into them,” Grandin says.

Grandin and others admit to being frustrated with genetic explanations for domestication. “There is a whole group of animal behaviorists who have been angry for years; you can just see it in their writing,” says Ray Coppinger, a behavioral geneticist at Hampshire College in Massachusetts. “Biologists have been divided into two camps: the population geneticists, busy counting genes, and embryologists, who went underground about Darwin’s time.”

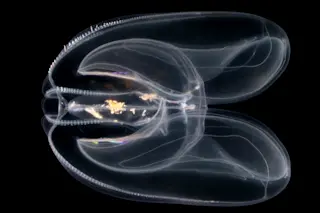

While geneticists see biological development from the inside out, embryologists and animal behaviorists see it from the outside in. Development doesn’t end at birth, Coppinger says. Each phase of life is a separate metamorphosis—an evolution complete unto itself, although always based on the same genetic information. Mammal bodies don’t just add some cells and tissue as they enter adolescence. They change radically, breaking down bone and rearranging it. The metamorphosis is no less complete than that of a caterpillar tearing itself apart to build a butterfly.

In this picture of development, the genome takes on an almost advisory role. It doesn’t direct development; it just sets the process in motion and stabilizes it. Coppinger imagines it as a series of accommodations, a sort of algorithm. As the embryo grows, each body part influences the others. When Coppinger studied the skulls of different dog breeds, for instance, he found a great deal of variation—a Saint Bernard’s head is many times the size of a Chihuahua’s—yet the size of their eyeballs varied not a whit. The Chihuahua’s dome-shaped head, in other words, is a by-product of its adjustment to its relatively enormous eyes, which are shaped by a limited set of genes.

Intense selection of the sort that creates domesticated animals puts a hold on development, like switching a train to a dead-end track. The result is what biologists call neoteny—the retention of undeveloped, immature traits in adulthood. Adolescent wolves are gawky and silly and have their own specialized foraging behavior. They wait at a set rendezvous point, then bark, whine, and beg for food—exactly like my dogs when I come home from a successful hunting trip to the grocery store. Dogs are genetically nearly identical to adult wolves, yet they neither look nor act like them. It’s not the information that is altered; it’s the way it is used.

In a way, humans are domesticated too. The skull of an infant chimpanzee looks remarkably like one of ours—in fact, it looks more human than the skull of an adult chimpanzee. Perhaps humans are neotenic apes, chimpanzees in a state of perpetual adolescence. Our evolution has focused so single-mindedly on brain size that the rest of our development has been put on hold—frozen in preparation for the next round of radical changes. We know that our DNA differs from chimpanzee DNA by a mere 2 percent. How could so much difference come from a mere 2 percent? The answer may not lie in that 2 percent at all but in how we use the other 98 percent.

A few evenings before I left Rarotonga, I took a walk down the beach under a breathtaking sunset. A short-legged dog named Lager was trotting beside me. It’s not surprising that humans pull other species into their orbit, I thought. We are many and we live large. Other animals see opportunities in the environments we destroy and rebuild. They come seeking food and shelter and the fruits of our excess. Never mind our loud, wayward, and toxic ways. After a few dozen generations, their descendants may even learn to enjoy us. But not always: If any species deserves to be called a hopeful monster, it’s us.