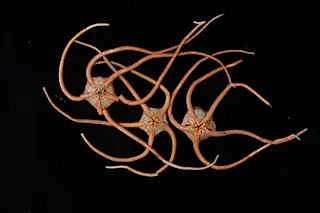

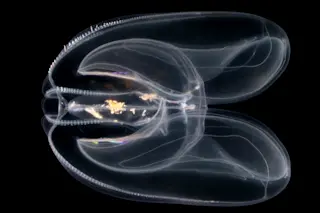

Every evening across the immense expanse of the tropical western Pacific, millions of white-shelled, dinner-plate-size mollusks begin an epic voyage. They rise from their daytime resting place—the dark, muddy ocean bottom a thousand feet or more deep—and slowly swim upward to shallow coral reefs where they feed for the night. These animals, the chambered nautiluses, look like snails with tentacles—their closest living relatives are the octopus and squid. More than that, though, they bear the look of a creature from a bygone era. Over the past 500 million years—before, during, and after the age of dinosaurs—more than 10,000 related species have roamed the seas. But in the 65 million years since the dinosaurs died out, the family to which the chambered nautilus belongs has gradually diminished. Today only a few species still exist, and they remain poorly known. Only recently have we learned some of the key facts about nautiluses, ...

Coils of Time

It's not easy studying the nautilus, a creature that lurks in the depths of the ocean and emerges only at night to prowl the coral reefs. But the rewards are great: discovering just how old a living fossil can be.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe