Photo by Ernie Mastroianni/Discover Mixed breed. Mongrel. Roadside setter. A something-something. Dogs of uncertain provenance get called a lot of things. When the animal arrives at a shelter, staff usually can make only an educated guess about the dog’s parentage. Most of the dogs at my local animal control are assessed as “pit mixes” upon arrival — including the three I’ve adopted over the past 2 years. But a pit bull isn’t a breed: it’s just a type of dog characterized by a short coat, muscular frame and broad, oversized head. All three of my dogs clearly — at least to my eyes — showed signs of specific breeds somewhere in their heritage: Tall and snow white Pullo looks like the breed standard for an American Bulldog. Tyche’s body is svelte like a boxer’s and inky black like some Labs. And lanky, long-limbed Waldo sometimes bays like a hound, especially ...

Can Doggie DNA Tests Decode Your Mutt’s Makeup?

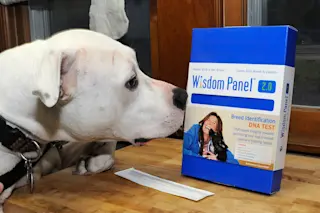

Discover how dog breed identification testing, like Wisdom Panel, unveils your dog's family tree using genetic markers in dogs.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe