Ancient Egyptian catacombs stretch for kilometers underground. Branching off of the tunnels are rooms, and those rooms are stacked to the ceilings with jars holding more than 1 million mummified African sacred ibises.

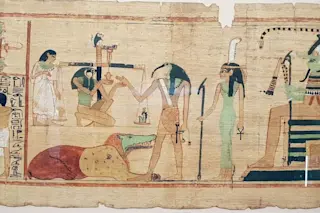

Egyptians buried millions of these leggy, long-beaked birds as prayer offerings to Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. Early archaeological work and snippets of ancient texts made most historians think these birds were raised in captivity somewhere near the catacombs. But a new analysis, published in the journal PLOSOne, of DNA from the mummified birds shows that the ibises were likely caught in the wild.

The finding is backed up by a suspicious dearth of any archaeological evidence of an ibis farm. Structures meant to mimic breeding grounds, for example, are absent, an indication that ancient Egyptians weren’t bird herding, says study coauthor Sally Wasef, an ancient DNA expert at Griffith University in Australia. The 14 ...