Raul Perez Lopez peers into the darkness of CJ-3, a cave that's mysteriously losing its oxygen. (Credit: Antonio Marcos Nuez) A deadly mystery lingers in a cave in northern Spain. A sign at the entrance warns visitors not to enter. For decades, speleologists have trained inside CJ-3, a 164-foot-deep cave in Cañon del Río Lobos Natural Park in the Soria province. But in 2014, visitors to the cave experienced something new at the bottom: they nearly suffocated, and one person fainted. The oxygen levels had suddenly, and inexplicably, dropped. The unusual incident prompted park officials to contact geologist Raul Perez Lopez of the Geological and Mining Institute in Madrid, Spain. Shortly after the first report, daredevil Perez dove into action. Perez along with two firefighters who specialize in mountain rescues went to investigate CJ-3. In the most dangerous move of his 20-year career, Perez, with the help of a firefighter, lowered himself by rope to the bottom of the deadly cave. “Upon arriving to the bottom, our gas detector started to beep because there was a lack of oxygen,” said Antonio Marcos Nuez, a geologist and firefighter who entered the cave with Perez to ensure its safety. “I’ve been entering caves for more than 25 years, and such a low oxygen percentage is a very unique situation.”

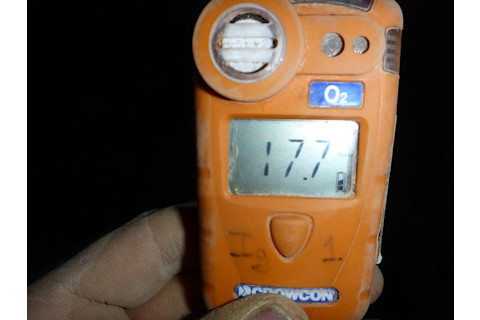

The oxygen levels in CJ-3 are mysteriously decreasing. (Credit: Antonio Marcos Nuez) Apart from detectors, they felt the effects of low oxygen: difficulty breathing, exhaustion, nausea and a sharp pain near their hearts. After less than five minutes, they quickly climbed the rope they had installed on the rock and rushed outside. The team did not return to CJ-3 again until December 2016. This time, they went with the proper tools, including breathing equipment that would provide oxygen for an hour. “(The first time) we didn’t have the right equipment and training and we weren’t prepared for the levels of oxygen that we found,” Perez says. So for two years he’s been learning techniques from firefighters to endure CJ-3’s unforgiving environment. “Like the astronaut in the movie ‘The Martian,’ I knew the air was going to run out. That was the hardest part for me, the psychological part,” he says. “Without the firefighters, this would have been impossible. We would not have entered the cave and removed the samples.” His daring commitment to science has yielded some clues about the enigmatic cave. Perez found that oxygen made up just 17.5 percent of the air composition inside the cave, compared to about 19 percent in similarly unventilated caves and 21 percent outside.

Raul Perez Lopez, who is leading the investigation of CJ-3, descends into its depths. (Credit: Antonio Marcos Nuez) “This cave is exceptional,” Perez says. “There has been a change there in recent years, that’s clear. Even in the deepest caves, the oxygen inside is as good as the oxygen outside.” To explain the oxygen deficit, Perez tested the cave’s air, measured the amounts of methane and carbon dioxide, and took clay samples from the ground for lab analysis. One early theory: The cave may contain bacteria that’s consuming methane and producing carbon dioxide, displacing the oxygen. “We know that something is consuming the methane inside and we have to find that source,” Perez says. He plans to test the air again and take more clay samples in the spring and summer. The new tests would show if oxygen levels change with the seasons. When it’s warmer air blows into the cooler cave. But when it’s colder outside, air rushes back out. “This is important because the quantity of oxygen that’s introduced in the entrance of the cave can depend on the low or high atmospheric pressure and of the temperature outside,” Perez says, adding that climate change may contribute to reduced oxygen levels. “There may have been a significant change in temperature in the last 30, 40 years that has made the cave blow more air toward the outside.”

Raul Perez Lopez takes measurements at the bottom of CJ-3. He wants to know why oxygen levels are dropping in the cave. (Credit: Antonio Marcos Nuez) Speleologists have been exploring the cave since at least the 1980s. Could the influx of visitors diminish its oxygen? “The problem with that theory is that at most, two or three people enter at a time and in the last two years, no one has entered,” Perez said. “And other small caves in this area, also used a lot, don’t have that problem.” The researchers will perform more tests in CJ-3 in March and also plan to measure the oxygen in nearby caves. “We have registers that show this process is happening in some caves in the area, but on a smaller scale,” Marcos Nuez says. “A nearby cave, called Las Tainas de Matarrubia, has a very small loss of oxygen, at 19.5 percent. But in no cave has the oxygen gone so low as in CJ-3.” In the meantime, the park has barred others from entering the cave, which has long served as a speleological tourism destination, says Perez, due to its ancient beauty— it’s also relatively easy to climb (at 164 feet deep, it’s considered shallow compared to other caves with a vertical drop). Perez hopes to solve its mystery this year. “We are getting information that I haven’t seen published in any scientific journals,” he said. “This cave has left an impression on all of us.”