The Maya Classic Period, which stretched between roughly 300 and 900 A.D. is typically seen as a kind of golden age for the ancient Central American civilization. Populations boomed, supported by vast systems of terraced fields and canals that provided irrigation in the dry months. Art and science flourished, while city-states grew side-by-side, if not always harmoniously.

Warfare during this period was traditionally thought of as somewhat ritualistic in nature, far from the kind of raze and burn aggression that defined the next era of Maya society, when people started to abandon cities. During the Classic period, major city-states like Tikal and Caracol would embark on campaigns of annexation, but their conquests wouldn’t typically result in total destruction. The prevailing view is that this period was, overall, a more peaceful time for the Maya.

But scientists say this understanding of the Maya is still overly simplistic. And a new paper in Nature Human Behaviour is challenging prevailing notions of Maya warfare, revealing the Classic period to be a time of greater strife than archaeologists thought.

A City in Flames

By pairing data from sediment cores with both written records from the Maya and archaeological evidence, a team of researchers says they’ve pieced together a tale of all-out warfare and near-complete destruction at a Maya city called Witzna.

Located in the north-eastern corner of Guatemala, near Tikal, the city was small but thriving for hundreds of years during the Classic period. It held a commanding view atop a ridgeline, and featured temples and a palace complex where the local elite would have ruled from. But a dispute with a larger neighboring city led to a ruinous war that left the city broken and vacant, its temples burned and its people taken away or killed.

This discovery came as a surprise for the archaeologists studying the city. Scientists didn’t think such city-destroying wars happened during this period of Maya civilization. But the new evidence they found is overwhelming.

There’s the ash, to begin with. At the bottom of a nearby lake, scientists discovered a blanket of charcoal three centimeters thick — the remnants of a major fire. David Wahl, a U.S. Geological Survey expert in studying ancient climates, turned up the ash layer in a sediment core he drilled in Laguna Ek’Naab, located about a mile away from the city. He dated the ash to just around the end of the 7th century A.D.

“I’ve been taking cores from this lake is this area and elsewhere for 20 years and I’ve never seen anything like this,” he says. “Just massive chunks of charcoal, a huge deposit indicating a massive fire event.”

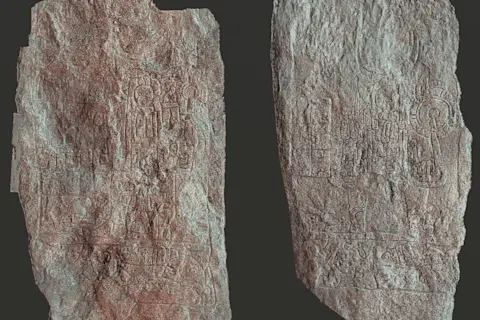

The sediment cores taken from a lake near Witzna. The cores contain a thick layer of ash around the end of the 7th century. (Credit: David Wahl)

David Wahl

Other clues from the sediment record hinted at the ash layer’s provenance. Wahl also looks for things like pollen grains and signs of erosion in his sediment cores — clues that give away the presence of people in ancient landscapes. Right after the fire, those things vanished.

“Following this fire event, all of our indications of humans in the watershed … essentially turn on a dime right at that same horizon and start to decrease dramatically,” he says.

Archaeological clues back this theory up as well. Excavations at Witzna, called Bahlam Jol by the Maya, show that the major structures at the site had all been burned. The team thinks it was the work of the nearby city of Naranjo, likely angry that Witzna had declared independence from them.

In Naranjo, archaeologists found a stela bearing both the name Bahlam Jol and the phrase “puluuy,” which in this context means “it burned.” The phrase has shown up elsewhere marking the destruction of cities, the researchers say, and it’s further evidence that Witzna was destroyed by Naranjo. There’s even a date for the city’s death, thanks to the extremely accurate calendars the Maya kept: May 21, 697 A.D.

Reevaluating War

Following the battle, which study co-author Francisco Estrada-Belli says likely involved large armies and a siege, the population of Witzna seems to have been absorbed into Naranjo. They may have been taken as slaves, a not-uncommon practice among the Maya.

The findings suggest that “total war,” or warfare that leaves cities and populations decimated, might have been more common among the Maya before their collapse than archaeologists thought. Other recent finds make a case for more structured warfare among the Maya as well. A fortress recently discovered near Tikal, the first of its kind found among the Maya, and a network of watchtowers throughout the Central American lowlands hint that large-scale warfare was a prevalent element of Maya society.

It counters one theory about their collapse during the 10th century. Archaeologists previously thought that the advent of more destructive warfare, likely brought on by drought and other hardships, was a signature of their final days. It now appears that it may have been a part of Maya civilization all along.