A few months ago, out of curiosity, I took a genetic test to trace my ancestry. The results mostly confirmed what I had already suspected: I was a blend of Eastern European and Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. Then came an offer to see a medical analysis of my DNA — an opportunity to learn about the bits of my genome that increase my risk of developing disease. Again, I was curious, but as I started ticking a series of boxes informing me that I could discover something upsetting, I suddenly thought to myself, “You know what? Never mind. I don’t have to know this.”

This decision was out of character. I always want to know things, preferably as soon as possible. After a job interview, I constantly refresh my inbox, impatient to hear back. But finding out if I get the gig sooner rather than just a few hours later changes very little.

Knowing my genetic risks and ways to mitigate them, however, is potentially life changing. So why was I so content to stay in the dark? As a neuroscience grad student, I decided to do a little digging to learn how humans can be so curious, yet simultaneously harbor such a love of ignorance.

The Story of Dopamine

As I searched through the science, it became clear that our desire to know things — or not — is closely tied with dopamine, the chemical messenger of the brain’s reward centers.

For decades, researchers have known that dopamine-releasing brain cells become highly active when we expect a reward or when we encounter rewards that are better than we anticipate. For example, if you assume you’ll do well on a test but unexpectedly ace it, your dopamine levels will spike. This spike compels us to repeat the same behavior or return to the same environment in search of more. But more recently, scientists discovered that dopamine cells don’t just care about tangible rewards. They also seem to care about information, even if it’s useless.

The key study came in 2009. Scientists at the National Institutes of Health trained monkeys to look at a screen in exchange for drops of water. Next, the monkeys got to choose between looking at a meaningless image or one that revealed the size of their next water drop. Getting this heads-up didn’t influence whether or not they got water, but the monkeys still heavily preferred the hint over ignorance. What’s more, dopamine-releasing neurons that buzzed with activity in the buildup to getting water also fired up when the monkeys were waiting to learn how big their next drop would be.

This discovery points to a fascinating possibility: The brain’s dopamine system treats the chance to obtain a reward and the chance to gain information as equally exciting. This might offer a clue as to why we often “just want to know.”

In the next few years, researchers observed something similar in humans. In studies where people anticipated information that would resolve a puzzle or trivia question, their dopamine hubs lit up, just as the monkeys’ had. More recently, in 2018, researchers at the University of Melbourne discovered a parallel between how the brain reacts when we’re anticipating both rewards and information, and how it reacts when those things fail to live up to our expectations.

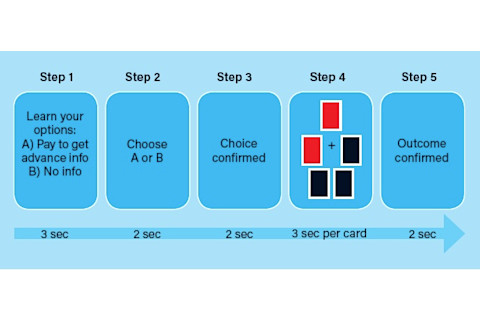

Their study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, recorded the electrical activity of 22 participants’ brains while they played a series of lottery games involving cards. Players had two options: remain ignorant of the lottery results until the end, or pay a fee, deducted from any winnings, to learn the outcome in advance. No matter their decision, players saw five cards, revealed one by one to be either black or red. For players who chose not to know the lottery outcome ahead of time, these cards didn’t matter. But for those who did want the scoop, a black majority signaled an upcoming win. Whenever participants saw a red card revealed, indicating they could be on their way to a loss, their brains produced a specific electrical signal. But it wasn’t the only time this signal showed up.

Sometimes, a card — either red or black — that made the outcome less certain would be revealed to a player who’d opted to learn the results in advance. Interestingly, when this happened, that same electrical signal showed up, regardless of the card’s color. Apparently, when the promise of obtaining useful information is denied, the brain reacts as if it missed out on an actual reward.

Tell Me, Tell Me Not

In one study testing how the brain treats information, volunteers played lottery games involving a series of cards. Players could choose to pay some of their winnings to learn the outcome of the next lottery in advance. Then, they were presented with a series of cards, either red or black. If they’d opted to learn the outcome in advance, they knew that a majority of black cards signaled an impending win. If they chose not to learn the outcome ahead of time, the ratio of colored cards didn’t matter. (Credit: Dan Bishop/Discover)

Dan Bishop/Discover

The Thrill in Knowing

Practically speaking, this neurochemical entanglement might explain why I often want to know things just out of curiosity. If both tangible rewards and information can be cashed in for a dopamine rush, then both have legitimate crave-worthy value. Now I wonder if my paying for my technically useless ancestry report is part of a drawn-out chase for a hit of dopamine. Accepting that my brain really does value information as much as it does physical rewards, that brings me to my next question: Why?

The research of Marco Vasconcelos, an animal behaviorist at Portugal’s University of Aveiro, gives me some insight. In a 2015 study on starlings, he describes how he gave the birds a choice between pecking two buttons. One button immediately informed them about whether they were about to be rewarded; the second provided no information but resulted in a higher chance of rewards. Shockingly, the starlings heavily preferred the informative, lower-reward button.

To Vasconcelos, this makes perfect evolutionary sense. “If uncertainty is not eliminated as soon as possible,” he explains, “an animal may [pursue prey that has] a reasonable probability of escaping.”

Similarly, we may actively avoid being uncertain about the future so we don’t waste time on fruitless pursuits — something that might have meant going hungry back when resources were scarce. This drive could have hard-wired our brains to constantly seek information. On a subjective level, this idea makes sense: I definitely hate uncertainty.

It’s All About How You Frame It

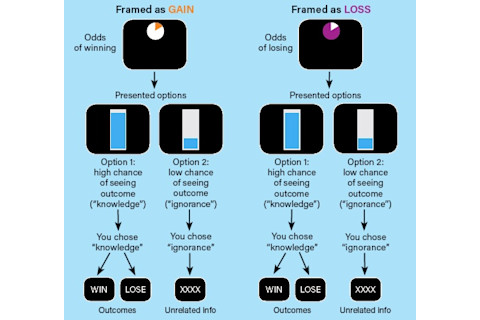

This lottery-based experiment investigated how the way information is framed impacts how inclined people are to want to learn it. Lottery rounds were presented as either a participant’s odds of winning, or their odds of losing. In each scenario, players were presented with two options: little to no chance of seeing your lottery outcome or a high chance of seeing your lottery outcome. They next made their choice, which was confirmed in the following step. Finally, if they chose to know their odds of winning or losing, they saw the results. If they chose to remain ignorant of the results, they were shown unrelated information. (Credit: Dan Bishop/Discover)

Dan Bishop/Discover

A Fear of the Unknown

Still, this doesn’t mesh with my choice to avoid seeing the medical analysis of my genome. How to explain that choice? Researchers at University College London and Washington University in St. Louis published a paper that helped me better understand.

In their study, published in 2018 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team set up a lottery scenario where participants had no control over the outcome. Players went through multiple rounds where they could either win or lose money at random and collect their total earnings at the end. But at the start of each round, they saw their odds, framed as a percentage chance either of winning or of losing on that turn. Once they knew the odds, players could then give their preference for learning the round’s outcome. Crucially, though, they knew their choice wouldn’t affect their total earnings. All the while, the researchers tracked the players’ brain activity.

The team found that, when probabilities were framed as chances of winning, people were much more likely to choose to be informed. And on those occasions, their reward circuits were highly active. But when probabilities were framed as a potential loss — even when the odds of winning and losing were the same — fewer people chose to be informed. And their brains reflected this paradoxical behavior with lower levels of activity in brain areas that pump out dopamine.

It seems that the biological equation information = reward comes with a serious caveat. “Our brains treat positive information as a reward to be approached, but negative information … more as a punishment to be avoided,” says Caroline Charpentier, the study’s lead author.

When I ask her why we evade negative information, she argues that it comes down to the value of beliefs. “When we have positive beliefs about what’s about to happen to us — we are about to get a salary raise — we feel good,” she says. “Meanwhile, if we have negative beliefs — we are about to receive negative feedback on an assignment — we feel bad.” So avoiding potentially negative information not only helps us reduce the uncertainty in our lives, it can help us try to keep our positive beliefs intact.

When I look back on my decision to remain ignorant of my genetic risks, I wonder if it was the potential of learning some bad medical news that trumped my usual frustration with uncertainty. After all, my years of studying the brain have made me all too aware of how untreatable many neurological conditions really are.

Ultimately, I agreed with my brain’s reasoning: Maybe it’s better not to know.

Sofia Neleniv is a neuroscience graduate student at Oxford University. This article originally appeared in print as "When Ignorance is Bliss."