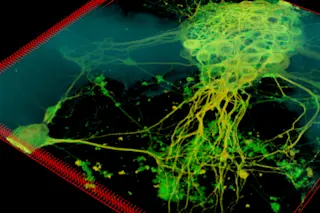

Shortly before 10:30 on a recent evening, with a nearly full moon luminous through mile-high air, Jonathan Van Blerkom climbed into his car, eased out of his driveway, and threaded his way through a quiet Denver neighborhood to check on the fate of some precious human eggs. They had been inseminated that morning, and some of them should be one-celled embryos by now. Van Blerkom’s day had begun more than 16 hours earlier, but human development works the night shift, so Van Blerkom does too. Every evening, weekends included, he sets out on this five-minute drive to do one of the things he does best: look at very early embryos, only hours after fertilization, to decide if they are likely to become babies.

The embryos had been incubating all day in a small laboratory at Colorado Reproductive Endocrinology, a private fertility clinic where Van Blerkom, a professor at the University ...