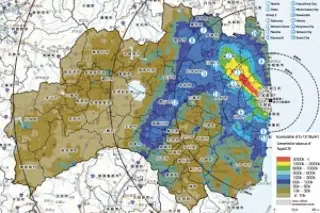

Fukushima prefecture: ground zero. World Health Organization Today marks the second anniversary of the tsunami that wiped out a nuclear plant on the coast of Japan and lead to a triple meltdown. The emotional fallout from the disaster has been an enormous setback for the promoters of fission-generated power. But of the four fundamental forces of nature, it is gravity, not nuclear, that has caused the most casualties at Fukushima. The death toll from the crashing waves killed some 20,000 people. But no one, including emergency workers at the plant, has died from the radiation, and no one has yet been diagnosed with a radiation-induced cancer. It is still very early. Ionizing rays -- the kind powerful enough to break molecular bonds -- can mutate genes, and the effects may not be apparent for decades. All we can do is predict. A report released late last month by the United Nations World Health Organization has provided the most authoritative estimate of what to expect. For all the suffering the disaster unleashed, the effects from radiation -- alpha, beta, and gamma rays -- are predicted to cause no measurable increase in the cancer rate for the general population of Fukushima prefecture or for the world beyond. People in the United States, loading up on potassium iodide tablets to protect their thyroid glands from wind-borne fallout probably put themselves at greater risk -- not from cancer but from other side-effects of the pills. Radioactive debris is deadly and unequivocally carcinogenic. But one of the most surprising things I learned while writing The Cancer Chronicles is how the long-term effects -- at Chernobyl and even Hiroshima and Nagasaki -- have caused much less cancer than our instincts might lead us to suspect. People who lived closest to the Fukushima plant will naturally be more effected than others. That is especially true for children, who will have the rest of their lives to accumulate the additional mutations that are a hazard of living on earth. Whether these occur spontaneously or are induced by carcinogens (naturally occurring or artificial), just the right combination can turn a cell malignant. If not stopped by the body’s defenses, it will begin multiplying to form a tumor -- or a liquid cancer like leukemia, a clogging profusion of white blood cells. Fukushima will give some of the children a head start on cancer. But not, the report predicts, a very big one. The worst case is for infants who received the most intense exposure. For 1-year-old girls who had been closest to ground zero, the chances of getting thyroid cancer before they are 90 will rise from 0.75 percent to 1.25 percent. Thyroid cancer is fortunately among the most curable. And many cases smolder for a lifetime never erupting into serious harm. For the boys in the same exposure group the lifetime risk may rise from about 0.21 to 0.33 percent. The report doesn’t say why women, in general, are more vulnerable to this cancer, but research suggests that the difference is probably related to the stimulating effects of estrogen on thyroid cells. Boys are more vulnerable to leukemia, and the rates for infants who received the greatest radiation doses might rise from 0.60 to 0.64 percent. For girls the change is from 0.43 to 0.46. For solid cancers in general, the youngest people exposed to the highest doses may see their risk increase over a lifetime by about 1 percentage point (1.1 for females. 0.7 for males). Again this is for infants, those with the most to lose. The effects drop rapidly for those exposed at age 10 or 20 or for anyone who wasn’t close by the plant when it ruptured. I can’t find in the 170-page report, even in its appendices, a count of how many people, children or adults, fall into the various exposure groups. The increased risk may be slight but how many additional cancers will it cause? In a different study two Stanford researchers have estimated 180 additional cases and 130 fatalities worldwide. A United Nations report issued 20 years after Chernobyl -- which released far more radiation than Fukushima -- predicted that among the 600,000 workers, evacuees, and residents who received the highest doses, there might be a total of 4,000 additional cancer deaths. That is compared with the approximately 100,000 fatal cancers expected to come from causes unrelated to the radiation. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the health of 90,000 survivors has been monitored since the bombings in 1945. There have been an estimated 527 excess deaths from solid cancers and 103 from leukemias. (Approximately 150,000 people died immediately from the explosions or within months from injuries and radiation poisoning.) Altogether about 1,900 cases of cancer, including those that were not fatal, have been attributed to the bombs. You can’t minimize the sadness of even one additional cancer. Or the injustice of any cases caused by the deliberate explosion of nuclear weapons. But I don’t think I’m alone in having expected that the numbers would be so much worse.

The Cancer from Fukushima (and Hiroshima)

Discover the long-term effects of radiation on Fukushima prefecture residents and the surprisingly low cancer risks post-disaster.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe