The elderly woman sitting in Robert Teunisse’s office seemed sane enough, but the story she told was decidedly odd. About two and a half years earlier, she said, she’d begun having strange visions. The first time it happened, she was sitting quietly at home when she suddenly saw three or four two-inch-high, stovepipe-hat-wearing chimney sweeps parading in front of her, ladders in hand. She was thinking, ‘Well, I’m going crazy now,’ recalls Teunisse, a psychiatrist at University Hospital in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. But they didn’t harm her, so she thought, ‘What the heck, I’ll try to catch me one.’ But when she went near, they disappeared. So she knew it was some kind of optical trick.

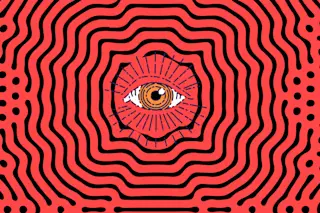

Teunisse had never encountered such a case, but he knew the woman wasn’t crazy. Unlike most mentally ill people who hallucinate, she was perfectly aware that the images she saw were not real. Teunisse later realized that she probably had Charles Bonnet’s syndrome, a disorder first described in 1760 by the Swiss philosopher for whom it is named. It is characterized by complex hallucinations in people who are psychologically normal. The disorder was thought to be extremely rare--so rare, in fact, that Teunisse thought he’d never see another case.

But two months later he did--and within a short time heard of several more. In reading up on Bonnet’s syndrome, Teunisse noticed that nearly all the reported cases had occurred among people who, like his first patient, were visually impaired in some way. He began to suspect that there might be a link between the two conditions and that Bonnet’s syndrome might not be that uncommon after all.

To confirm his suspicions, Teunisse studied 505 visually impaired patients at his hospital. Their average age was 75, and their handicaps ranged from glaucoma to the breakdown of the macula, a small area near the center of the retina. He found that 60 of the 505 met the criterion for Bonnet’s syndrome: they had frequent hallucinations but recognized them as such.

What causes the hallucinations? No one knows. Some researchers theorize that the brain produces spontaneous images, which are usually suppressed by normal visual input from the eyes. When that input is impaired, the theory goes, the spontaneous images may enter consciousness as hallucinations. Or perhaps, says Teunisse, damaged cells in the eyes produce nonsense stimuli, which are then transformed by a creative brain into sense.

Although there is no treatment for Bonnet’s syndrome, Teunisse points out that it is a far less disturbing diagnosis than psychosis--the label doctors naturally tend to pin on hallucinating patients. Many patients were very happy to hear about this, Teunisse says. Doctors and patients should recognize the syndrome and should not be worried about mental disease.