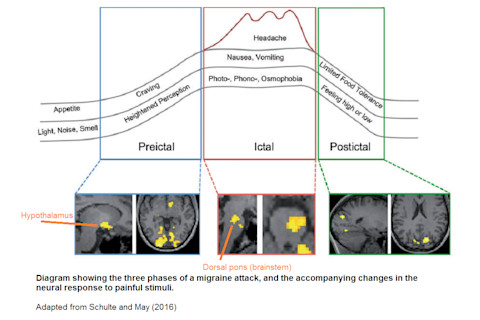

Migraines are a very unpleasant variety of headaches, often associated with other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia (aversion to light) and visual disturbances. Hundreds of millions of people around the world suffer regular migraines, but their brain basis remains largely unclear. Now a new paper reports that the origin of migraines may have been pinpointed - in the brain of one sufferer, at least. German neuroscientists Laura H. Schulte and Arne May used fMRI to record brain activity in one migraine sufferer, a woman, who was scanned once per day for 30 days straight.During the month of the study, the patient suffered three migraines, lasting one or two days each. She chose not to take any medications during the study period. To evoke brain activity, Schulte and May exposed the patient to a small amount of ammonia vapor, a painful and unpleasant stimulus. Schulte and May found that on the day before a migraine struck (i.e. the 'preictal' or prodromal phase) evoked neural activity in the hypothalmus was higher, and functional connectivity between the hypothalamus and the brainstem was increased. During the migraine itself (the 'ictal' phase), hyperactivity was seen in an area of the brainstem called the dorsal pons. These results are interesting because the dorsal pons has previously been found to be hyperactive during migraine. It's been dubbed the brain's "migraine generator". Schulte and May's data suggest that this is not entirely true - rather, it looks like the hypothalamus may be the true generator of migraine, while the brainstem could be a downstream mediator of the disorder.

Schulte and May say that a hypothalamic origin of migraines would help to explain some of the symptoms of the disorder, such as changes in appetite, that often accompany the headaches. This is because the hypothalamus is well known for its role in regulation of eating and drinking. This is a unique study in the field because of its intensive scanning schedule of a single individual (although it's not quite as many scans as Russ Poldrack had). That's also it's weakness, though: it remains to be seen whether these results hold up in other migraineurs. The authors conclude that

The main finding of this study is that the hypothalamus, depending on the state of the migraine cycle, exhibits an altered functional coupling with the spinal trigeminal nuclei and the region of the dorsal rostral pons. More specifically, the hypothalamus is significantly more active within the last 24 hours preceding the onset of migraine pain and shows the greatest functional coupling with the spinal trigeminal nuclei, whereas during the ictal state, the hypothalamus is functionally coupled with the dorsal rostral pons, an area that was previously coined ‘the migraine generator’... In conclusion, our data suggest the hypothalamus to be the primary generator of migraine attacks which, due to specific interactions with specific areas in the higher and lower brainstem, could alter the activity levels of the key regions of migraine pathophysiology.

Then again, Schulte and May don't address the question of why the hypothalamus triggers migraines in some people, or what causes migraines to occur on particular days and not others.

Schulte LH, & May A (2016). The migraine generator revisited: continuous scanning of the migraine cycle over 30 days and three spontaneous attacks. Brain : a journal of neurology PMID: 27190019