In the rehearsal space of the Boston band What She Said, Earl Miller lays into his bass guitar, plucking out a funky groove. He sticks out his tongue Mick Jagger style, as the band’s drummer hammers away behind him, clowning it up for photos splashed onto social media. In a black band tee, faded cargo pants and signature newsboy cap, Miller looks like a seasoned musician you’d see in any corner dive bar.

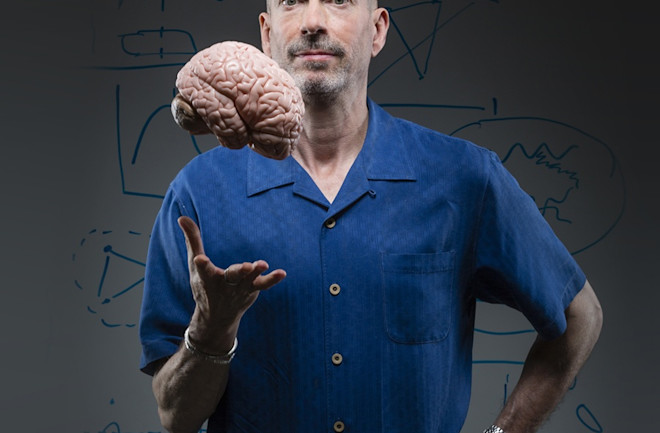

But at his nearby office at MIT, Miller is nothing if not professorial. How could that rocker in the cap be the same bookish academic now gazing solemnly at me across his paper-strewn desk at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory?

The jarring contrast between the two Earl Millers is a fitting way to begin a discussion of the pioneering neuroscientist’s work.

After all, some of Miller’s biggest contributions to the field over the past 20 years have explored exactly how contrasts like these are possible; how it is, in other words, that human beings — or any other animal with a brain — are able to seamlessly adapt behavior to changing rules and environments. How is it that distinct populations of brain cells, or neurons, are able to work together to quickly summon an appropriate response? How do we know when it’s fitting to play a Patti Smith bass line, and when it’s time to explain the complex workings of brain waves?