While reading The Founders of Evolutionary Genetics I encountered a chapter where the late James F. Crow admitted that he had a new insight every time he reread R. A. Fisher's The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. This prompted me to put down The Founders of Evolutionary Genetics after finishing Crow's chapter and pick up my copy of The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. I've read it before, but this is as good a time as any to give it another crack. Almost immediately Fisher aims at one of the major conundrums of 19th century theory of Darwinian evolution: how was variation maintained? The logic and conclusions strike you like a hammer. Charles Darwin and most of his contemporaries held to a blending model of inheritance, where offspring reflect a synthesis of their parental values. As it happens this aligns well with human intuition. Across their traits offspring are a synthesis of their parents. But blending presents a major problem for Darwin's theory of adaptation via natural selection, because it erodes the variation which is the raw material upon which selection must act. It is a famously peculiar fact that the abstraction of the gene was formulated over 50 years before the concrete physical embodiment of the gene, DNA, was ascertained with any confidence. In the first chapter of The Genetical Theory R. A. Fisher suggests that the logical reality of persistent copious heritable variation all around us should have forced scholars to the inference that inheritance proceeded via particulate and discrete means, as these processes do not diminish variation indefinitely in the manner which is entailed by blending. More formally the genetic variance decreases by a factor of 1/2 every generation in a blending model. This is easy enough to understand. But I wanted to illustrate it myself, so I slapped together a short simulation script. The specifications are as follows: 1) Fixed population size, in this case 100 individuals 2) 100 generations 3) All individuals have 2 offspring, and mating is random (no consideration of sex) 4) The offspring trait value is the mid-parent value of the parents, though I also including a "noise" parameter in some of the runs, so that the outcome is deviated somewhat in a random fashion from expected parental values In terms of the data structure the ultimate outcome is a 100 ✕ 100 matrix, with rows corresponding to generations, and each cell an individual in that generation. The values in each cell span the range from 0 to 1. In the first generation I imagine the combining of two populations with totally different phenotypic values; 50 individuals coded 1 and 50 individuals coded 0. If a 1 and 1 mate, the produce only 1's. Likewise with 0's. On the other hand a 0 and a 1 produce a 0.5. And so forth. The mating is random in each generation.

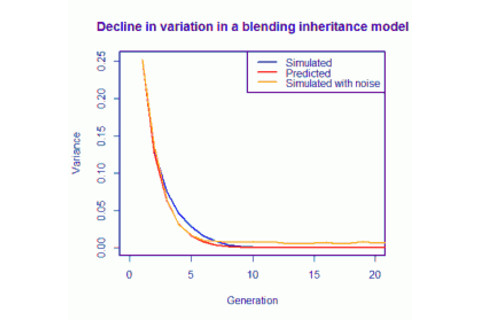

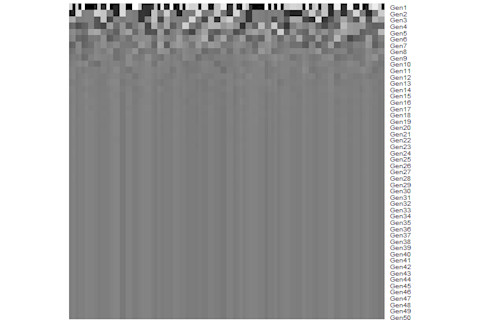

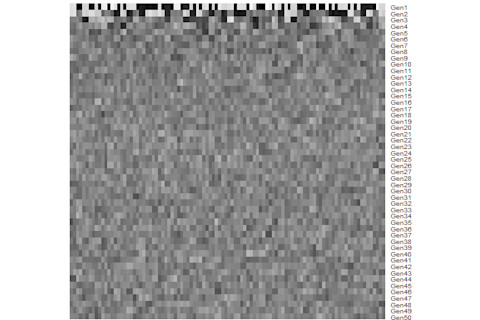

The figure to the left illustrates the decay in the variance of the trait value over generation time in different models. The red line is the idealized decay: 1/2 decrease in variance per generation. The blue line is one simulation. It roughly follows the decay pattern, though it is deviated somewhat because it seems that there was some assortative mating randomly (presumably if I used many more individuals it would converge upon the analytic curve). Finally you see one line which follows the trajectory of a simulation with noise. Though this population follows the theoretical decay more closely initially, it converges upon a different equilibrium value, one where some variance remains. That's because the noise parameter continues to inject this every generation. The relevant point is that most of the variation disappears < 5 generations, and it is basically gone by the 10th generation. To maintain variation in a blending inheritance model requires a great deal of mutation, the extent of which is just not plausible. To get a different sense of what occurred in these two particular simulations, here are heat maps. The interval 0 and 1 now have shading in each sell. I am displaying only 50 generations here. The top panel is one without noise, while the bottom panel has the noise parameter.

The contrast with a Mendelian model is striking. Imagine that 0 and 1 are now coded by two homozygote genotypes, with heterozygotes exhibiting a value of 0.5. If all the variation is controlled by the genotypes, then you have three genotypes, and three trait values. If I change the scenario above to a Mendelian one than variance will initially decrease, but the equilibrium will be maintained at a much higher level, as 50% of the population will be heterozygotes (0.5), and 50% homozygotes of each variety (0 and 1). With the persistence of heritable variation natural selection can operate to change the allele frequencies over time without the worry that the trait values within a breeding population will converge upon each other too rapidly. This is true even in cases of polygenic traits. Height and I.Q. remain variant, because they are fundamentally heritable through discrete and digital processes. All this is of course why the "blond gene" won't disappear, redheads won't go extinct, nor will humans converge upon a uniform olive shade in a panmictic future. A child is a genetic cross between parents, but only between 50% of each parent's genetic makeup. And that is one reason they are not simply an "averaging" of parental trait values.