Researchers in Sweden and the U.K. landed in the news over the summer, seeming to claim nearly 40,000 functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies could be invalid. The problem? The most popular statistical analysis software packages could indicate significant brain activity where there wasn’t any, more than half the time.

FMRI is becoming a more common imaging technique in neuroscience largely because it maps brain activity over time. (Unlike MRI, which maps brain structure, fMRI reveals blood flow, a proxy for activity.) Once the MRI machine cranks out images, statistical analysis software pinpoints which brain areas were significantly more active and when.

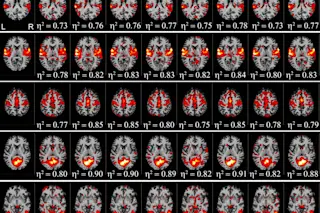

The team claims the software packages they examined weren’t calibrated with real data, just simulated data. So they used fMRI scans from 499 healthy people in a resting state, and analyzed the data as they would in a traditional fMRI study. The researchers realized that one particular analysis ...