Quick review. In the 19th century once the idea that humans were derived from non-human ancestral species was injected into the bloodstream of the intellectual classes there was an immediate debate as to the location of the proto-human homeland; the Urheimat of us all. Charles Darwin favored Africa, but in many ways this ran against the cultural grain. The theory of evolution was birthed before the highest tide of the age of white supremacy and European hegemony, and Darwin's model had to swim against the conviction that Africans were the most primitive of the colored races. After the waning of the ideological edifice of white supremacy, and the shock it received during and after World War II, the debates as to the origin of humanity still remained contentious and followed the same outlines (though without the charged normative inferences). But as the decades wore on many more researchers began to believe that Darwin was correct, and that the origin of humanity lay in the African continent. First, the deep origin of the human lineage in Africa was accepted, but eventually a more recent expansion out of Africa was argued for by one school. The turning point in these academic disputes was the popularization of the "mitochondrial Eve" theory of the 1980s. What some paleontologists had long argued, that anatomically modern humans have their locus of origin in Africa, was supported now by research from genetics which indicated that Africans were the most basal clade of humans on a continental scale, so that non-Africans could be conceived of as a subset of Africans. From this originates the chestnut of wisdom that Africans have more genetic diversity than all other human populations combined. By the year 2000 one could say that the "Out of Africa" triumphalism had proceeded to the point where an almost exterminationist model had taken hold when it came to the relationships of anatomically modern H. sapiens, and other groups which had evolved outside of Africa over the past million or so years, such as the Neandertals.

But the theoretical dichotomies were too coarse and absolute as it turns out. A division between multiregionalist phyletic gradualism, where H. sapiens evolved out of its hominin ancestors concurrently on a world wide scale, and a model of rapid expansion of one tribe in Africa to replace all others in totality, may have been warranted in the age of classical genetics and a morphometric analysis, but now we can look at the raw genomic material in a more fine-grained fashion. In fact, we can now look at the genomic patterns of variation among extinct hominins! Though there have long been hints that the expansion-and-replacement paradigm was too extreme from the genetic and morphological data, with the publication last spring in Science of a paper which made the claim for admixture between Neandertals and non-Africans in the range of 1-4% in all non-African groups based on a comparison of Neandertal and modern human genetic variation, one can dismiss absolutist expansion-and-replacement as self-evidently true orthodoxy. But one orthodoxy has no given way to another, and the shock to the old models presented by the data has not resulted in the coalescence of new robust paradigms. We live in a time of scientific troubles, so to speak. One of the more notable results in the Science paper from last spring was that all non-Africans had about the same admixture in relation to the Neandertal reference genome, ~1-4%. This means from the Orkneys to New Guinea. Because Neandertals were distributed only in the western half of Eurasia this implies that the admixture was an early event. By the time of modern human expansion across Eurasia, Australasia, and the New World, it had become equally distributed across the individuals within the population. Recall the contrast between African Americans and Uyghurs. Among the Uyghurs the ancestral quanta are equitably distributed from individual to individual, but among African Americans there remains substantial intra-population variance. The reason is that African Americans are quite new, an order of magnitude younger than the Uyghurs in a genetic sense, and admixture is still occurring into the African American population from the ancestral groups. The Uyghurs as we known them today genetically are probably ~1,000-2,000 years old (though their cultural origins are both more and less ancient, as a matter of linguistics in the former, and ethnic self-conception as a Muslim East Turkic group in the latter). The implication here is clear: there was a pause in the Out of Africa movement, where the proto-non-Africans mixed with a Neandertal group, possibly in the Middle East, and only began a massive demographic expansion after an unspecified sojourn. A paper from last spring makes this all explicit:

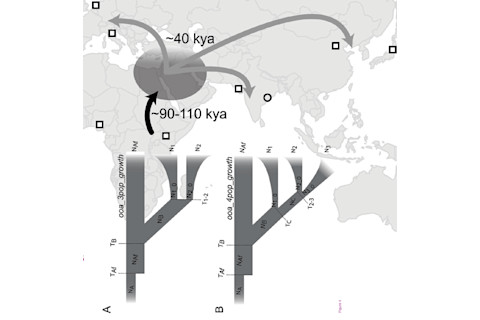

A more likely explanation for the OoA bottleneck is that Eurasia was populated by a larger population that had been relatively isolated from other modern human populations for tens of thousands of years prior to the expansion. The first fossil evidence for modern humans outside of Africa is in the Middle East at Skhul and Qafzeh between 80,000-100,000 years ago, which is at least 20,000 years prior to the Eurasian diaspora. If a population of modern humans remained in the Middle East until the expansion into Eurasia, there would have been sufficient time for genetic drift to reduce heterozygosity dramatically before the Eurasia expansion. This “Middle East isolation” hypothesis provides a robust explanation for the relative homogeneity of European and Asian populations relative to African populations (see Figures 3A-B) and is supported by a recent maximum likelihood estimate of 140,000 years ago for the time of Eurasian-West African population separation . Interestingly, a recent study of the Neandertal genome suggests that the non-African individuals, but not the Africans, contain similar amount of admixture (1-4%) with the Neandertals . The authors suggest that the admixture must have happened between the Neandertals with an ancestral non-African population before the Eurasian expansion. Given the fossil, archaeological, and genetic evidence, the Middle East isolation hypothesis warrants rigorous evaluation as whole-genome sequence data become available.

Now the same group has published a follow up paper in Genome Biology which fleshes out the Deep Time aspect of human evolutionary history by looking closely at the genetic variation of an under-sampled population: South Asians. You may have noticed that the HGDP populations include Pakistani groups as South Asian exemplars. That's apparently because during the Permit Raj era in India the government was wary of cooperating with the HGDP consortium. But more recently the barriers have come down in India, and one can viably supplement the data sets with Indian Americans. So the GIH sample in HapMap3 consists of Gujaratis from Houston. At ~1.25 billion, or nearly 20% of the world's population, South Asians are a critical portion of the "big picture" when it comes to world wide genetic variation. Genetic diversity in India and the inference of Eurasian population expansion:

To analyze an unbiased sample of genetic diversity in India and to investigate human migration history in Eurasia, we resequenced one 100 kb ENCODE region in 92 samples collected from three castes and one tribal group from the state of Andhra Pradesh in south India. Analyses of the four Indian populations, along with eight HapMap populations (692 samples), showed that 30% of all SNPs in the south Indian populations are not seen in HapMap populations. Several Indian populations, such as the Yadava, Mala/Madiga, and Irula, have nucleotide diversity levels as high as those of HapMap African populations. Using unbiased allele-frequency spectra, we investigated the expansion of human populations into Eurasia. The divergence time estimates among the major population groups suggest that Eurasian populations in this study diverged from Africans during the same time frame (approximately 90-110 thousand years ago). The divergence among different Eurasian populations occurred more than 40,000 years after their divergence with Africans.

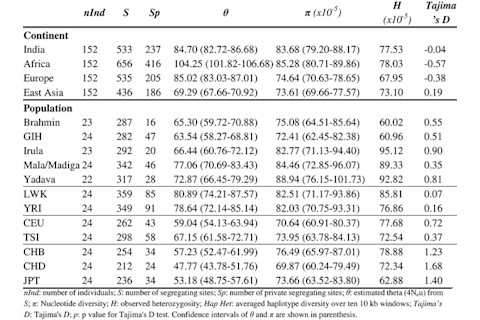

First, I want to put into the record that I think there are high enough uncertainties (evident in the confidence intervals in the paper itself) that we need to be careful about taking the divergence times from their results as values we'd bet the house on. Someone with a better knowledge of the fossils (e.g., John Hawks) or controversies about the mutational rates (e.g., Dienekes) can comment on the plausibilities of the dating. But, I think we can infer that there was a time lag closer to a 10,000 years order of magnitude than 1,000 years when it comes to the Middle Eastern sojourn of non-African humans. The basic method here is that the research group zoomed in on a ~100 kb region of the genome, on chromosome 12, and surveyed their Indian populations, as well as the HapMap3 ones. This is important because the SNPs in the HapMap probably exhibit an ascertainment bias toward variants in European and other more widely surveyed groups. The fact 30% of the SNPs in the South Indian groups seem to not be found among the HapMap populations confirms this hunch. Before digging into the details of the paper, let's note that the South Indian groups are from the state of Andhara Pradesh, Brahmins, a lower caste group (Yadava), Dalits (Mala/Madiga), and a tribe (Irula). This is a case where even more thorough coverage is necessary. There is some suggestion that South Asian groups have a long history of endogamy and genetic peculiarities, which would limit the usefulness of extrapolations from this sample. Even within the HapMap Gujarati sample there seems to be two clusters when the PCA is used with reference to the European samples. There are basically three portions of the paper: - A survey of conventional population genetic statistics, θ = 4Neμ (Ne = effective population, μ = mutation rate) π = nucleotide diversity H = heterozygosity D = Tajima's D - Measures of genetic distance between contemporary populations, Fst and PCA - Finally, taking the genetic variance from the ~100 kb and plugging it into explicit models of human evolutionary history Table 1 (I reformatted) shows the genetic statistics by "continent." Indian includes some Gujarati individuals. They sampled out of the HapMap populations to equalize the numbers.

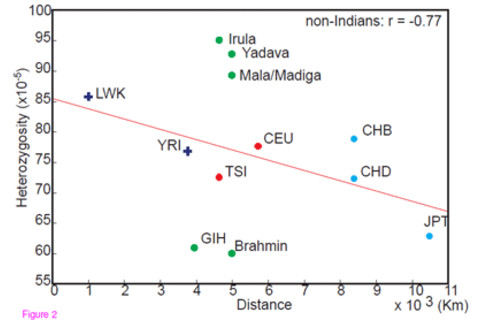

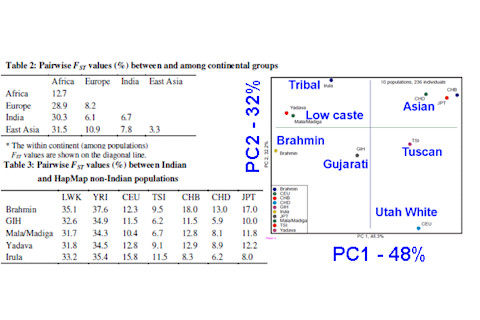

Some of these results are striking. The general truism is that Africans are the most diverse population in the world, but some of the South Indian groups are very diverse indeed. Of particular interest though is that some Indian groups are not very diverse at all. What's going on here? Here you have to look at the specifics of each group. It is likely that South Indian Brahmins are the result of a relatively recent population expansion, with some uptake of other genes through hypergamy. A paper from last year argued that all Indian populations can be modeled as a two-way admixture of different quantities from two ancestral groups, Ancient North Indians and Ancient South Indians. The heterozygosity values may be explained in such a fashion, though the relatively low values for Gujaratis and Andhara Pradesh Brahmins would still surprise. Frankly, I'm just mostly confused by the diversity statistics. Probably the substructure through endogamy and population bottlenecks are obscuring broader dynamics. We can, though, conclude that the idea that all non-Africans are uniformly homogeneous in comparison to Africans may not hold water. Figure 2 above illustrates this by plotting heterozygosity vs. distance from Africa. Next, let's move to genetic distance. There's two ways you can look at this: a summary statistic like Fst, which partitions between and within population variance, and PCA, which visualizes the largest dimensions of variations in the data set. So you have both below (reedited for reasons of space):

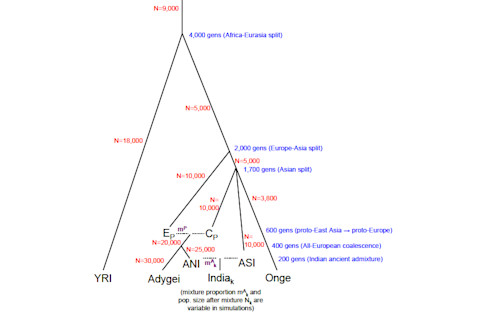

In the generality the results are expected, but there are weird details. For example, the Brahmins from Andhara Pradesh are on the margins, where you'd expect them to cluster with the Gujaratis. The Gujaratis are closer to the Chinese from Denver than Utah Whites? This is a provisional paper, so I'm almost wondering if there's a typo or coding error here, as I don't understand how the GIH can be so close to the Tuscans and Chinese from Denver, and much further from the Northern Europeans and Chinese from Beijing. The two European and Chinese samples are rather close in other analyses. So let's get to the real deal. The modified Out of Africa model where non-Africans take a "break" after they leave the mother continent:

I've mashed up the figures. The models were generated by looking at allele frequencies. They took the variants they found by sequencing the ~100 kb on chromosome 12, which was in a very gene-poor region so as to bias it toward neutrality, and plugged them into a few models in the ∂a∂i program. I'll jump to the text here:

...the divergence time between African and the ancestral Eurasian population (88-112 kya, CIs: 63-150 kya) is much older than the divergence time among the Eurasian groups (27-39 kya, CI: 20-59 kya). The more recent divergence time and the low migration rate estimates among the current Eurasian populations support the “delayed expansion” hypothesis for the human colonization of Eurasia (Figure 5). Consistent with previous studies...these estimates indicate that a single Eurasian ancestral population remained separated from African populations for more than 40 thousand years prior to the population expansion throughout Eurasia and the divergence of individual Eurasian populations.

Manafi al-Hayawan, Adam and Eve

Take a good look at those confidence intervals. We know that some of those have to be false: the bones don't lie. From what little I know a very young consensus date for the settlement of Australasia by modern humans is 40,000 years ago

. That happens nicely to be their median, but the dispersion toward younger dates is probably not right, unless Aborigines are a separate population who are remnants of an earlier wave of migrants (or the current Aborigines replaced earlier waves). It is also hard to reconcile these dates for the diversification of non-African humanity with very old dates for Chinese fossils which exhibit some elements of modern morphology

. In the broad outlines I think we can accept that the model outlined in this paper may be correct. It would explain the uniform admixture of Neandertal in non-Africans, since they'd need time as a compact population before demographic expansion to integrate the Neandertal genes as part of their genetic background. But before the Neandertal genome came out there were plenty of papers which purported to show how there was no archaic admixture in modern humans, and plenty of papers which did claim there was evidence for such admixture. The point is that these computational models are sensitive to their inputs, and being models they simplify what really happened. In the discussion the authors repeatedly observe that migration between the various non-African demes doesn't effect the outcome. That is fine, but there is modestly strong evidence that

the Indian samples that they're using are an admixed population of old.

That would make me skeptical of claims about dating the separation of "Indians" when Indians are themselves possibly a compound between other groups. Below is the model presented from Reconstructing Indian population history

:

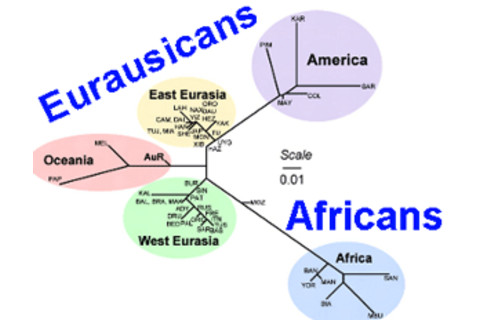

The teens of this century are going to be very exciting when it comes to reconstructing human evolutionary history. You'd be a fool to put bets on any horse at this time.

Addendum:

I need a term for non-African humanity. So I'm making up one right now: Eurausicans. From Eurasians, Australasians, and Americans. Citation:

Jinchuan Xing, W Scott Watkins, Ya Hu, Chad D Huff, Aniko Sabo, Donna M Muzny, Michael J Bamshad, Richard A Gibbs, Lynn B Jorde, & Fuli Yu (2010). Genetic diversity in India and the inference of Eurasian population expansion Genome Biology : 10.1186/gb-2010-11-11-r113