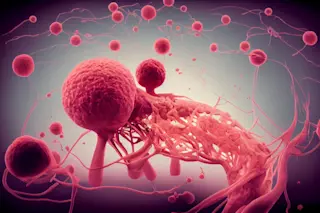

Mrs. CHANG LAY IN THE EMERGENCY WARD, fighting. She was fighting terminal cancer, pain, and despair, and as her oncologist, I was called to see her. Just back from a farewell visit to her parents in Taiwan, she lay on her gurney behind a green curtain, her son beside her. Her knees were drawn up, her arms crossed, her eyes closed. When I said hello and touched her frail shoulder through the worn hospital gown, she turned, her body stiff beyond her years. She fought to sit up, to smile, to regain the politeness and grace that were second nature to

her. But fighting took everything she had. She grimaced and fell back against her plastic pillow.

I can’t, was all she said. I can’t.

Mrs. Chang had cervical cancer and it was killing her. She was not yet 50, and because of her cancer she never would be. Her ...