Advancements in the medical sciences follow a well-trod path: observation of a problem, reasoned hypothesis and experimentation, and implementation of a solution. This course is governed by logic and, occasionally, reinforced by unorthodox thinking with the ultimate goal of improving the viability of man. An exception to this rule is the invention of the rubber glove. One of the most important breakthroughs in the practice of medicine was born not of careful problem-solving and the scientific process, but of a romantic gesture, a clinical schoolboy’s crush, an event which one observer described as “Venus [coming] to the aid of Aesculapius.”To step back a bit, let us begin by realizing that any progress in infection control in medicine throughout the modern history of the field came in fits and stops. In the nineteenth century, hospitals were “houses of death” to be avoided at all cost due to non-existent standards of sanitation. Hands went unwashed between patients and coats spattered with pus and blood were habitually reused for surgeries. In 1843, Oliver Wendell Holmes proposed that puerperal fever, an often fatal infection following childbirth, had an infectious, transmissible component to it - one directly linked to the hygiene of physicians. This would be later verified in 1847 by the physician Ignaz Simmelweiss as he documented a decline in maternal deaths after requiring his students to rinse their hands in antiseptic chlorine solution (1). However, Simmelweiss was widely derided by his peers for lacking an empirical explanation for his findings and it would be many years before his proposal was accepted.

A portrait of a young William Halsted, circa 1874. Image: Yale University Manuscripts & Archives Digital Images Database. Click for source.

Thirty years later, in 1876, the English surgeon Joseph Lister began using phenol acid to clean his instruments and the hands of his surgical associates. Even wounds were bathed with the caustic solution. His favorable results were published in what became a seminal article, “Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery,” and Lister’s concepts of sterility and the prevention of contamination greatly influenced a young and forward thinking surgeon, William Halsted, who would soon put them into practice.

Today, Halsted is considered one of the founding fathers of modern surgery, known for developing innovative techniques to treat bone fractures, hernias and gallstones, as well as devising the radical mastectomy to treat breast tumors (2). He performed the first emergency blood transfusion on his sister using blood drawn from his own veins. The use of silver, a naturally antibacterial element, in wound dressings was one of Halsted’s discoveries, as was his work in implementing the use of cocaine, his greatest vice, as an anesthetic.The innovation of Halstead’s which has had an effect on the greatest number of patients and physicians alike, however, was no profound response to a pathological challenge, but only a practical solution to a thoroughly nonfatal inconvenience.In 1889, a young nurse named Caroline Hampton moved from New York City to Baltimore to work in the newly-opened Johns Hopkins Hospital. She was quickly assigned to the position of chief nurse of Halstead's operating theatre.At the time of his professorial appointment to Johns Hopkins Hospital, Halsted routinely relied on the use of antibacterial solutions of mercuric chloride and carbolic acid in the operating theatre. Anything and everything intimately involved in an operation, including the surgical instruments and the probing hands of the operating staff, were to be doused in the disinfectant in accordance with the sterilizing technique pioneered by Joseph Lister twenty years prior. But for Caroline Hampton, the future Mrs. Halsted, exposure to the powerful chemicals left her with a rash on her hands so severe that she considered leaving the job and the hospital (3). It was a possibility that the surgeon could not abide. Halsted coolly writes of the problem and reports on his inventive solution:

In the winter of 1889 and 1890 - I cannot recall the month - the nurse in charge of my operating-room complained that the solutions of mercuric chloride produced a dermatitis of her arms and hands. As she was an unusually efficient woman, I gave the matter my consideration and one day in New York requested the Goodyear Rubber Company to make as an experiment two pair of thin rubber gloves with gauntlets. On trial these proved to be so satisfactory that additional gloves were ordered.In the autumn, on my return to town, an assistant who passed the instruments and threaded the needles was also provided with rubber gloves to wear at the operations. At first the operator wore them only when exploratory incisions into joints were made. After a time the assistants became so accustomed to working in gloves that they also wore them as operators and would remark that they seemed to be less expert with the bare hands than with the gloved hands. (4)

This famous paragraph documents the beginning of a historical transition in the field of medicine: the emergence of aseptic technique and infection control within the operating room. It also documents, albeit in somewhat less than passionate terms, a budding courtship that would bloom into marriage in only a year. One wonders, when it comes to Venus and Aesculapius, who came to the aid of whom? We scientists perhaps might like to imagine that it was Halstead’s divine hygienic inspiration that won the nurse’s heart, rather than this physician’s tenderness giving rise to scientific progress. But I digress ...

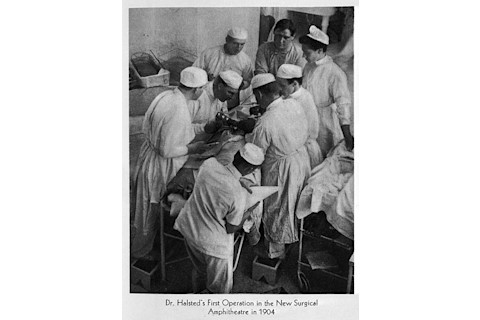

Wiliam Halsted and Caroline Hampton in the operating room. He is seen on the left, leaning over the patient. She is seen in the upper right, wearing her famous gloves. Image: Wellcome Images.

Initially, the gloves were used only by nurses and assistants, but soon the habit would spread to the practicing physicians. The aptly-named Dr. Joseph Bloodgood, a surgeon and protege of Halstead’s, began to use the gloves in 1896. Three years later, he published a book that documented an almost 100% decrease in the infection rates after over 450 hernia operations were completed while wearing gloves (1). Following this publication, Halsted himself began to regularly don gloves in the operating theatre and would later ask, “Why was I so blind not to have perceived the necessity for wearing them all the time?”

Though he pioneered their use in the operating room, Halsted cannot be credited with inventing the concept of protective gloves, as they had been in use for over 130 years, first appearing in 1767 when a German physician used obstetric gloves molded from sheep colon (2)(5). The gloves were used not to prevent the spread of infection from practitioner to patient, but rather to “lessen tissue laceration when the hand was placed into the vagina,” a concern consistent with the spurious theory of “spontaneous generation” that, at the time, presupposed that wound infections resulted from toxins released from necrotic tissues (2). As we have seen, of course, the conceptual and practical emergence of “aseptic medicine,” an operation without the threat of infectious complications, began long before Halsted, but it was this prominent surgeon who planted the seed that would transform operating rooms at the turn of the century. Rubber gloves became a necessary component of the operating theatre and the hospital as we know it.A request from a nurse for protection from the caustic weapons of the evolving, maverick war on infection would not only blossom into a love affair and marriage, but also radically change the practice of medicine and advance public health. William Halsted was a brilliant and innovative surgeon who pioneered many groundbreaking innovations in surgical technique, pharmacology, and medical care, but it was a well-timed romantic gesture that would help popularize the use of rubber gloves in medicine and surgery, making them a standard and essential piece of equipment in operating rooms around the world.Resources To learn more about Caroline Hampton Halsted, check out "Caroline Hampton Halsted: the first to use rubber gloves in the operating room." The practice of surgery has come a long, long way. But not every development has been a success. From the Body Horrors archives: Quackery & Poison: A Ballsy ProcedureReferences 1) SR Lathan. (2010) Caroline Hampton Halsted: the first to use rubber gloves in the operating room. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent).23(4) :389-92 2) LI Spirling & IR Daniels. (2002) Historical perspectives on health: William Stewart Halsted - surgeon extraordinaire: a story of drugs, gloves and romance. J R Soc Promot Health.122 (2): 122-124 3) Z Mikić (201) [The gloves of love] Med Pregl. 63(1-2): 133-7 4) SB Nuland. (1995) Doctors: The Biography of Medicine. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday 5) SR Lathan (2011) Rubber gloves redux. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)24(4): 324