Quick with a smile and even faster with a pun, native New Yorker Stephen Morse doesn’t seem like a man preoccupied with mass killers.

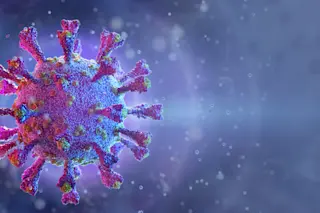

As a boy he toyed with the idea of becoming an Egyptologist or herpetologist — “I spent a lot of time trying to catch snakes in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey” — but eventually he chose microbiology. A lifelong lover of solving puzzles, Morse gravitated toward some of the most mysterious microbes: killer viruses that seemed to strike from out of nowhere, sometimes reaching pandemic levels.

“I like intellectual challenges — that’s probably my greatest weakness,” jokes Morse, sitting in his office at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, where books, often two or three rows deep, are crammed floor to ceiling.

Morse is credited with creating the term emerging infectious diseases in the late 1980s to explain viruses that can exist for years ...