Autism Linked to Excessive Early Brain Growth

Autism is devilishly difficult to diagnose at an early age. Ambiguous symptoms—delayed language, poor attention, emotional withdrawal—generally appear between the ages of 2 and 3. Parents may seek the wrong treatment, or worse, the condition may go unrecognized. A study published in the July 16 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that doctors may be able to anticipate the onset of autism much earlier by using a simple tool: a tape measure.

Researchers from the School of Medicine at the University of California at San Diego analyzed medical records of 48 autistic children and found that small head circumference at birth, coupled with a sudden excessive increase in head size during a child’s first year, appears to be linked with autism. The most severely autistic children were those whose heads grew the fastest.

Eric Courchesne, the principal author of the study, says that the “burst of extreme growth” is primarily in the frontal cortex—the center of complex cognitive functions—and typically lasts only a few months, ending somewhere between the sixth and 14th month of life. At that critical stage, brain cells begin developing in response (and in proportion) to the baby’s first experience of the outside world. Too-rapid growth, outpacing what Courchesne calls “the guidance of experience,” may produce so much “neural noise [that] the infant would lose the ability to make sense of its world and withdraw.”

The fact that the accelerated rate of brain growth occurs in an infant’s first year suggests that autism springs from a genetic or prenatal biological cause, not from later environmental factors such as vaccinations, adverse allergic reactions, or exposure to toxins. Perhaps most important, it opens the way to earlier diagnosis and treatment. And as Courchesne observes, “the earlier the intervention, the better the outcomes of therapy.”

—Michael W. Robbins

Scientists See Yet Another Reason to Go to the Gym

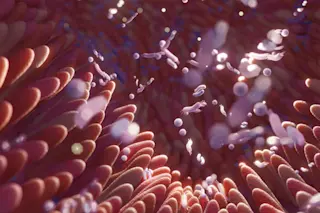

Everyone knows that aerobic exercise is usually good for your heart. Now it turns out to be good for your brain as well. From about age 30 onward, everyone loses brain cells—both gray matter, or neurons, where conscious thinking takes place, and white matter, or axons, which serve as a connective network. This cellular loss is matched by an overall decline in cognitive performance. But researchers have found that cardiovascular fitness helps keep brain cells alive and well.

Cognitive neuroscientists at the Beckman Institute of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and at Wayne State University in Detroit analyzed functional magnetic resonance images of the brains of 55 volunteers ranging in age from 55 to 79. “Essentially, it was like an epidemiological study,” says Stanley J. Colcombe, a Beckman Fellow and the team leader. “We took a big sample, held for variables, and looked at what was left. It was known from prior animal studies that cardiovascular health had effects on brain health. So we went looking for the impact of fitness on cortical density.”

The volunteers ranged from couch tubers to marathon runners. The researchers first established fitness levels by means of a one-mile walk and a treadmill stress test. Then they examined the density—the concentration of functioning cells—in the gray matter and the white matter of each subject’s brain. After factors such as diet, education, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and hypertension were statistically controlled to isolate the effect of exercise, the team found a clear correlation between greater fitness and greater brain-tissue density.

Unfortunately, taking up cardiovascular exercise upon, say, retirement, won’t restore those brain cells you’ve already lost. But, says Colcombe, it certainly will improve the cognitive performance of what you have left.

—Michael W. Robbins

Meditation Apparently Activates Positive Areas Within the Brain

Meditation is often promoted as a tool for alleviating stress and anxiety, but exactly why it calms the nerves has long mystified scientists. A study published in February offers a few clues. For the first time ever, a team of medical researchers led by Richard Davidson, director of the Laboratory for Affective Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, showed that meditation activates an area of the brain associated with positive emotions. A randomly selected group of middle-class volunteers with stressful jobs took an eight-week course in Mindfulness Meditation given by author Jon Kabat-Zinn, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. A control group from the same pool of volunteers did not receive any meditation training. To establish a baseline, everyone was given electroencephalograms.

After the course, both groups were asked to pick two intense emotional experiences they’d had—one good, one bad—and write about them while their brains’ electrical activity was monitored. Whether they summoned a happy or an unhappy memory, the meditation group showed markedly more electrical activity in their left prefrontal cortex—the locus of positive, optimistic emotions—than they had in their baseline test or than the control group had in either reading. “This shows that these changes are not just ‘in your head,’ so to speak,” says Davidson. “The meditation produced real changes in the brain.”

—Michael W. Robbins

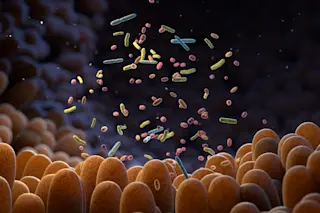

Chronic Stress Triggers Overeating

Ever wonder why you find yourself raiding the icebox or tearing through a bag of potato chips when you feel completely frazzled? In September a team led by physiologist Mary Dallman of the University of California at San Francisco subjected lab rats to a series of stress tests and learned how comfort food manages to comfort. During times of chronic stress, foods laden with sugar and calories act as a brake on the body’s overworked emergency response system.

Say your dander is up because your boss just threatened to fire you. Acute stress, says psychologist Norman Pecoraro, provokes a flurry of brain signals to the adrenal glands, which in turn release a flood of cortisol and other hormones. This release is self-limiting; the cortisol itself eventually triggers a shut-off mechanism. When the immediate crisis passes, the cortisol level abruptly decreases. But when you encounter threatening situations for days or weeks on end, the brain reacts differently. Instead of shutting off the cortisol, it tells the adrenal glands to make even more. High-energy foods help restore hormonal calm.

Unfortunately, such stress-induced overeating has unsightly—and unhealthy—side effects. Test rats that ingested large amounts of sucrose and lard to combat stress developed potbellies within four days.

—Annette Foglino