Valley fever, a potentially fatal dust-borne infection caused by a soil-dwelling fungus,has lurked in the deserts of the Southwest United States for hundreds of years, if not longer. But in the past decade, the disease has seen an uptick in cases, leading to a “silent epidemic,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Because of increasing development in arid climates where the fungus lives, as well as better testing and diagnosis, the infection’s incidence has skyrocketed, reaching 22,500 cases in 2011, up from 2,265 in 1998. But with many cases going unreported, experts believe as many as 150,000 people may be sickened annually.

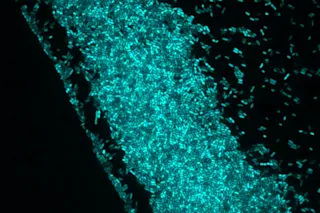

Medically known as coccidioidomycosis, or cocci for short, the lung infection is caused by a fungus in the mushroom family that begins life as a tiny, single-celled spore. Even a light breeze can carry the spores aloft, and when inhaled, they can penetrate deep inside ...