You never know how far you can go until you’ve left everything behind. And as Eric Drew waited alone in the cold rain on a dock of the Seattle waterfront, he had come to the bitter edge.

Icy water lapped against the planks as he leaned on a cane, barely able to stand. Though only 36 years old, this former high school quarterback and magazine model now resembled a war victim. His once-dark, wavy hair was completely gone, his blue eyes were sunken. On his back he carried a small sack filled with plastic bags of antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals. A hose ran from the bag straight through a catheter in his chest. If he caught even the slightest cold, he could be dead.

It was February 2004, and Drew was dying of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a savage cancer of the blood and bone marrow. In a healthy person bone marrow acts as a sort of factory of stem cells, the vital cells that mature and divide to form other essential blood cells throughout the body. The leukemia, however, was making Drew’s factory go haywire. Instead of producing healthy lymphocytes, white blood cells that fight infections, his bone marrow was unleashing abnormal lymphocytes into his bloodstream. Even worse, the bad cells were multiplying so rapidly that they were overtaking his healthy cells—making him harrowingly prone to deadly infections.

Chemotherapy and radiation had completely compromised his kidneys and destroyed his immune system, requiring a constant infusion of potassium, magnesium, vancomycin, Cipro, and other medications to help keep him alive. He had spent the past year in and out of hospitals from Stanford to Seattle. He had endured seizures and infections and got so bloated with fluids that his limbs blew up like some hideous cartoon. Most recently, he had undergone a bone marrow transplant that, he was told, was his final hope.

But his illness was not what brought him to the waterfront that night. As he lay in his hospital bed, Drew had been getting harassing phone calls from irate banks and credit card companies demanding payment for purchases he had never made. Taking him for dead, someone had stolen his identity, he discovered, and was racking up thousands of dollars in bills. Now, after getting a tip-off, he had come to the docks to meet an anonymous informant who claimed to have the skinny on the thief.

While Drew’s family and doctors pleaded with him to rest, Drew couldn’t let it go. As he had learned, there was only one way to save himself. He had to fight.

When you’re on your way to do good, you don’t think everything will turn bad. As Drew drove to the American Red Cross to donate blood on December 3, 2002, in San Jose, California, he had every reason to feel on top of the world.

Drew was living a charmed life. He had been a director of business development for a software company. He had a gorgeous girlfriend, a 21-year-old college student named Nicole Floor. He had just been approved for a million-dollar loan on a beautiful house in his lifelong hometown of Los Gatos, a hilly community near San Jose. Gregarious and popular, Drew had tended bar at the hottest club while in college at San Diego State University. For a while he had topped all his friends’ buddy lists by managing a chain of go-go clubs.

Since hitting his thirties, however, he had begun taking steps to find more meaning in his life. Adopted as an infant, he had recently been seeking out his birth family and had connected with his half siblings across the country. To give back to his community, he had been donating blood once a month.

As he arrived at the Red Cross this Tuesday, however, Drew wasn’t feeling as healthy as normal. He had been unusually fatigued for the past couple of months. “Gosh, Eric,” the nurse said, “you look kind of pale. Your red cell count, which is usually 45 to 50, is down to 30. That’s borderline anemic. It doesn’t look alarming, but you should go see a doctor.”

Drew took her advice but didn’t think much of it until his receptionist buzzed him a few days later. “The doctor’s trying to get hold of you,” she said. “He says your blood test is back.”

Why the urgency? Drew wondered as he dialed his doctor. “There’s something concerning me here,” the doctor explained, “and I need you to see a blood specialist on Monday.”

What particularly troubled Drew was the fact that his doctor had hustled an appointment for him during the hematologist’s lunch break. As Drew pulled into the parking lot for his appointment, his stomach twisted. The sign at the San Jose Medical Center read “Cancer Center.”

As the doctor walked in, Drew nearly leaped from his seat. “Doc,” he said, “what’s going on?”

“It’s too early to tell,” the doctor said. “You traveled to Africa recently, right?”

Drew nodded.

“It could be the late onset of malaria. Let’s test the bone marrow and find out.”

Drew could not sleep for the two days it took to get the results. He drove back to the cancer center with his mother, Cindy, for emotional support. This time when the doctor came into the examination room, he was crying. “This is the hardest part of my job,” he said as he put his hand on Drew’s knee and told him he had cancer. “Your bone marrow is 100 percent cancerous. I don’t know how you’re standing up. You need to go to the Stanford Cancer Center. If you don’t check in tomorrow, you won’t live five days.”

“I have some very bad news.” Drew could hardly believe the words appearing on his computer screen as he typed. After seeing the doctor, he had gone home to Los Gatos and begun e-mailing his friends and family. “I have been diagnosed with a very severe, rare, and deadly form of leukemia, which generally kills within a few weeks,” he wrote. “The odds are not good for me to survive....”

As his cursor blinked, there was no way he could describe the depth of sadness he felt. He was a young guy moving ahead in every aspect of his life, and then the carpet got ripped out from under him. He felt as if his entire identity was being stripped away. For Drew, a type A quarterback, the situation was flat-out unacceptable. He made Nicole a promise when she came to visit him that night. “I’m going to beat this,” he said.

Drew had overcome adversity his whole life. Born out of wedlock during a Texas hurricane, he was put up for adoption at birth. As a kid in Los Gatos, he fended for himself, hunting rattlesnakes and quail for fun and food. He drew inspiration from his high school football coach, Charlie Wedemeyer, who was paralyzed from Lou Gehrig’s disease and bound to a wheelchair and respirator. Wedemeyer never gave up. Before every game, Drew and his teammates would say, “Let’s do this for Charlie.”

As his cancer treatment began on December 16, Drew brought that same conviction with him. “You’re the Stanford Cancer Center,” he told his doctors. “I trust you. Hit me with what you got. Don’t worry, I won’t let this kill me.”

But he quickly learned how difficult the experience would be. Drew possessed the Philadelphia chromosome, a mutation that would make his cancer even more difficult to fight. Fearing that his veins would collapse, the doctors injected the chemotherapy cocktail directly into his spine and heart. The experience was brutal. Drew felt as if his skin was burning and his head was going to explode. The cancer, meanwhile, was already ravaging his body.

Drew was not just fighting a disease, he was fighting a system. He had to be his own advocate. Just before his treatment, he heard from his half sister, Alexa Gregory Martin, who worked as a physician’s assistant in Seattle, that his radiation would almost certainly leave him sterile. Yet no doctor had suggested that he bank his sperm. Against their advice, he delayed his treatment while he banked sperm. He was convinced that one day he would see the birth of his own kids.

As the illness and treatment progressed and winter turned to spring, Drew would have precipitous highs and lows. One night Nicole’s phone rang, and it was Drew, sounding in good spirits. “Do you want to drive up?” he said. “Let’s watch a movie.” Nicole slipped into her pajamas and grabbed her overnight bag. Maybe this wouldn’t have to end, she thought; maybe they would go back to normal after all. When she arrived at the Stanford medical center an hour later, however, her dreams were quickly dashed. Sirens were going off in the hallway, and an urgent voice came over the intercom: “Code blue 39A!” Wait, Nicole thought, that’s Eric’s room.

Nicole walked in to a nightmare. Drew was surrounded by a half dozen hospital workers. They were giving him chest compressions. His body was shaking uncontrollably. Nicole was in shock, unable to speak or cry or move. “You have to leave,” one of the workers told her. A bad reaction to an antifungal drug had caused his heart rate to fall abruptly, but they were able to stabilize him. The experience, and the thought of weeks of harrowing treatments to follow, took their toll. When Nicole went into the ICU later that night to see Drew, he was crying.

Images courtesy of Eric Drew | NULL

“I just don’t want you to go through this,” he said. “You have everything going for you. You don’t have to be in this situation. I want you to know you can leave whenever you want.”

“I can’t,” Nicole replied. “I’m too invested in this. No matter what, I’ll be here. I’ll support you.”

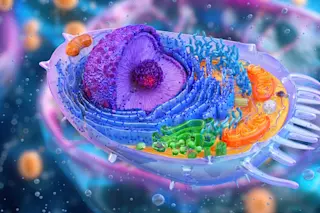

Though the chemo and radiation had prolonged his life, by the summer of 2003 Drew knew the treatments alone were not going to save him. For that, he needed a bone marrow transplant. Bone marrow contains immature stem cells that can grow into three types of cells: red blood cells, to transport oxygen; white blood cells, for fighting infections; and platelets, to facilitate clotting when needed.

In a transplant, healthy stem cells are harvested from a donor and infused intravenously into the recipient. The healthy new cells then find their way to the bone marrow, where, if all goes well, they engraft and provide a new immune system. For Drew’s specific disease, the typical long-term survival rate for a transplant ranges from 40 percent to 70 percent—but for someone who is Philadelphia positive, as Drew was, the survival rate is lower, 10 percent to 50 percent. Success depends on how well the donor’s and recipient’s chromosomes match; the better the match, the greater the odds of survival. According to the National Marrow Donor Program, depending on race, between 60 percent and 87 percent of potential recipients find at least one match, and a total of more than 260 patients receive transplants every month.

Finding a match, however, would be an uphill battle for Drew. The optimal match—a full sibling—was not an option for him, since he had none. And a unique protein in his blood narrowed the pool even more. He needed all the help he could get.

Drawing on his years of entrepreneurial skills and quarterback leadership, Drew spent the summer organizing a bone marrow drive. He sent e-mails around the world to everyone he knew and began getting checks from as far away as South Korea. Friends were organizing prayer chains from Jerusalem to Africa. Drew, though not holistically minded in the past, went full steam: He started doing yoga and taking megadose multivitamins. He went into the woods with a Mongolian shaman who burned a goat carcass on his behalf. Drew even took to the street, sitting on a busy corner in a chair and handing out flyers. He soon had 1,000 volunteers working to help him and had raised an astonishing $250,000, which he used to start the Eric Drew Foundation to help others. The emotional support was not just incredible, he felt, but lifesaving, a lesson for anyone fighting a disease. Don’t just lie back, he wanted to tell people. Get out there and do something, whatever you can.

One day, after all his hard work, he was with a band of volunteers when he saw that he had a telephone message from the bone marrow search coordinator at Stanford. Drew gathered everyone around to hear what he was sure was good news. “Hi, Mr. Drew,” the message said. “I just wanted to confirm that we have exhausted our search capability and there’s nothing else we can do. I’ll have a hospice nurse call you. Sorry, and good luck.”

How do you say good-bye to your life, to the people and things that form your identity? It was an impossible question that Drew had to answer as he sat in his apartment boxing his possessions away in September 2003. Good-bye books. Good-bye college photos. Good-bye friends. In a sad twist of fate, he also had to say good-bye to Sammy, his chocolate-brown Chesapeake Bay retriever, who had to be put to sleep after being diagnosed with cancer.

With no bone marrow donor found, Drew’s odds of recovery had plummeted from slim to the cusp of none. Most people would have just taken Stanford’s advice at that point, contacted a hospice, and called it a day. But Drew was not ready to die yet. As fate would have it, his half sister, Alexa, had been working at the transplant center at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, and she told him about another option: an experimental procedure known as haploidentical transplantation. The procedure involved taking someone with only half the matching chromosomes and using him as a donor.

To prepare for the transplant, Drew would have to undergo more debilitating chemo, and even then the odds were frightening—the chance of engraftment is lower, and there’s more risk of dying from complications. But it was a chance he was willing to take. And another of his half siblings, an importer in Chicago named Michael Gicewicz, volunteered to be the bone marrow donor.

Drew resumed chemo treatments, slipping in and out of consciousness. One day he woke up to find his entire body had begun shaking uncontrollably, and he could not move. Drew came out of the episode to find his mother at his side. “I can’t do this anymore,” he told her, crying. It was too much, too painful. But with the transplant just a couple of weeks away, she urged him to hang on.

Two days before the transplant, the hospital called Drew to tell him that his half brother, Michael, had mononucleosis and that it would be months before he could be up to the surgery required for his donation. Devastated, Drew dialed Alexa to tell her the news. She didn’t skip a beat. “I’ll be your donor, Eric,” she said. Two days before Christmas, Drew received Alexa’s stem cells through a catheter in his chest. It would be three months before he would know if the stem cells had grafted, and he knew the odds were low. But he had no idea how low he could get.

During his treatment in Seattle, he began getting strange calls from credit card companies thanking him for his application. Drew shrugged it off as best he could until the collection agents started arriving at his door. There were a half dozen accounts opened in his name, with almost $10,000 in charges. “Please stop this!” Drew told one of the banks on the phone. “I’m in a hospital dying!”

But there was no stopping this thief. Here Drew was, on the verge of death, and someone was stripping away his last shred of humanity. He felt that his identity was being taken on every level. The disease was robbing him of his life. Some criminal was stealing his identity. And the medical system had swiped his individuality. He wasn’t even Eric Drew anymore; at the hospital, they just called him Patient Room 232.

Late one January night, as snow came down outside his window, Drew’s anger boiled over. He began throwing things, breaking glasses until he was exhausted. There was no more energy left. He was sick of being angry, sick of blaming the system and the hospital workers and anyone else in his line of sight. I can point fingers everywhere, he thought, but where will it get me? To my grave. This is not how I’ll go. I won’t be a victim anymore. I’m going to fight back.

During his treatment in Seattle, he began getting strange calls from credit card companies thanking him for his application. Drew shrugged it off as best he could until the collection agents started arriving at his door.

Having worked in banking, Drew knew how to take action. He ordered up a credit report and found the address where his imposter was receiving his mail. Against his loved ones’ wishes and his doctor’s orders, Drew had his mom drive him to the address, in a poor part of town. Weak from chemo, he pounded on the front door, not even knowing what he’d do if someone answered. No one did. Drew had the mail rerouted to his own address and, with the bills in hand, uncovered the trail of the identity thief’s purchases.

Drawing on his marketing skills, Drew sought the help of a local TV news station, which broadcast his story on the air. They filmed Drew in a wheelchair outside his hospital, pleading for information. Sure enough, the calls came in—many of them from crackpots. Still, Drew had to follow each lead. One of them was from an anonymous tipster who claimed to have photos of the person who fit the profile. When Drew told his family he was going to meet this character on the Seattle docks, they thought he was crazy. But as much as Nicole feared for his well-being, she could see that, in a strange way, the identity theft was bringing Drew back to life. She saw a glimpse of the old Eric, the one who wasn’t sick, the proactive go-getter who wouldn’t take no for an answer. “OK,” Nicole told him, “but if you don’t call me in an hour, I’m going to call the police.”

The tipster, it turned out, was a dead end—just a well-meaning citizen with the wrong information. Drew was ready to pack it in when the local TV station contacted a Lowe’s store, spurring the retailer to check its surveillance videos. With the help of Drew’s records, they pinpointed a purchase to a specific time and date, and the TV station put the grainy footage on the news for everyone in town to see. As Drew lay in bed watching the video, he couldn’t believe his eyes. There was the fake Eric Drew, a middle-aged African American man in hospital scrubs. His name was Richard Gibson, a lab technician at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance who had tested Drew’s blood.

Drew was indignant. This guy had taken him for dead and took him to the cleaners. He was told by attorneys that he could have sued the hospital for millions, but now he just wanted justice. Four days later he got it. On March 2, 2004, Gibson turned himself in and became the first person in the country to be convicted for violating the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which protects patient privacy. Gibson was later sentenced to 16 months in prison and ordered to pay more than $9,000 in restitution.

Drew had fought to get back his good name and won. Now he was ready to reclaim his life.

Drew did not have long to celebrate his victory over Gibson. By the end of March, the necessary three months had passed since his bone marrow transplant—and it was time to get the results. It wasn’t good news. Alexa’s stem cells, Drew learned, had failed to fully engraft. “There’s nothing else we can do,” his doctors told him. “We can arrange for hospice care.”

By now, Drew was numb—how much more could his emotions be stretched? Despite the grim prognosis, the Hutchinson center offered to do a second transplant using his half brother Michael’s bone marrow. He was planning to do it, but the strain was making itself felt. He took a trip to California to reconnect with Nicole, who had just graduated from college. As he sat with her in her apartment in Chico, she teased him. “You haven’t given me a graduation present,” she said.

“OK,” he said, reaching into his pocket. “Here it is.” He handed her an engagement ring. Nicole was surprised, and afraid—afraid to take it seriously, because that would mean she had opened her heart and soul to him. She had been through the death of her mother from cancer and couldn’t bear to lose someone again. She loved him; she just didn’t want him taken from her. When she said yes to his proposal, she did it as much to give him hope.

She had also given him something else: a lead on a cure. A year earlier, after some sleuthing on ClinicalTrials.gov, the government site that keeps tabs on experimental cancer treatments, Nicole had stumbled on an article about an alternative source of stem cells: umbilical cord blood. Initially they had written this treatment off and chosen to move ahead with the marrow transplant. But now they were willing to take a second look and sought out the advice of a specialist, Tibor Kovacsovics, an associate professor of medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University Cancer Institute.

Because of the political controversies over embryonic stem cells, information about cord blood stem cells had been unclear. But this was a noncontroversial source, Drew learned. Donations came from around the world, either from people giving cord blood to public banks or through private services that bank families’ blood. Since the mid-1990s, facilities such as the University of Minnesota’s had been performing cord blood transplants because of an implicit benefit. “Umbilical cord blood contains an enriched population of bone marrow stem cells,” says Daniel Weisdorf, director of the Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at the university. “There are large numbers of bone marrow–like stem cells with huge growth potential.”

But there was a hitch. Researchers found that the tiny amount of stem cells harvested from one cord blood source was not enough to serve a full-grown adult. So beginning in 2000, the University of Minnesota began a new approach: using stem cells from two umbilical cord blood sources, which increased the chances of engraftment in adults to 90 percent.

Drew’s doctors in Seattle had nothing to say when he asked them about the procedure; it wasn’t something they performed. Drew was incensed that he would not have even known about this option if Nicole had not gone online, but by now he understood that the fight for survival begins and ends with the patient. So he called Minnesota and made the plan. There would be risks, of course. Once again Drew’s immune system would have to be eradicated—this time with six times the radiation and more chemo. There was a 50 percent chance that he wouldn’t survive that alone. In all, his odds of survival were about 25 percent, but this was his last hope.

Drew took Nicole on the long drive to the University of Minnesota and checked into the hospital. He had a treadmill brought into his room and walked on it for a few days. But his strength didn’t last long. Doctors began wiping out his immune system again with a blast of 1,320 centigrays of gamma radiation 20 minutes twice a day for four days.

On July 23, 2004, Drew was infused with the stem cells from two sources—a newborn girl in Italy and a baby in Ohio. Hopefully, one would take. But that was just the beginning. Between the cumulative effects of the radiation and chemo and his body’s reaction to the new stem cells, the physical effects were gruesome. His skin began peeling off like strips of bacon. His body was on fire. His temperature hit 106.8 at one point, and he had to be packed in ice. Blood was coming out of his eyes and ears. Inside his body, his intestinal lining was falling apart. He had severe diarrhea filled with blood.

“It’s OK, you can die,” said Drew's mother. “No, I’m not ready,” he said. “I’m going to keep fighting.”

To survive, Drew demanded near-lethal doses of morphine. And he called on every reserve he had—yoga, controlled breathing. When he didn’t have the strength to walk on his treadmill, they came to take it away, but he refused to let them. “No,” he said, “I’ll get back on it.”

Drew focused on his dreams of being healthy and alive. Before long his sense of reality began to shift, so that he felt more in touch with his sleeping state than with being awake. He slipped into psychoses and hallucinations. A few times, he ripped the cords from his body and tried to escape the hospital. When he looked up at the caretakers around his bed, they appeared to him as angels.

At one point his mom, Cindy, couldn’t take seeing him in so much pain. She wanted him to know that he didn’t have to do this for her or for anyone else. “If you’re hanging on for me or my husband or whomever, it’s OK,” she said, “but you don’t have to do this for us.” And, painfully, she added, “It’s OK, you can die.” Drew took her hand. “No, I’m not ready,” he said. “I’m going to keep fighting.”

But all he could really do was wait to see whether the stem cells would take hold.

By November 2004, although his condition was still critical, Drew decided to go home for Thanksgiving. Six months later he went for a bone marrow biopsy from his hematologist. This was the moment of truth. When the call came with the results, he could barely hold on to the phone. He was in his parents’ house with Nicole. “Just to let you know,” the doctor said, “you’re 100 percent in remission.”

The engraftment had worked. A wave of relief washed over Drew as he hugged his family. There was more, the doctor said. Drew wasn’t just a new man. “Your blood is 100 percent female,” he said. Eric Drew, now a 37-year-old man, had the blood of an Italian girl. It was like something out of a Tom Clancy thriller. If he cut his finger while committing a crime, investigators would think that the criminal was a girl.

Drew had fought for his life and won. Like millions of people every year, he had had numerous reasons along the way to give up—but he refused. In retrospect, his mother thinks the experience of the identity theft may have saved her son. “He would thank Richard Gibson for taking his identity,” she says. “It gave him something to fight for and reenergized him after that.” Alexa also credits Drew’s tenacity for his recovery. “He’s a pain in the ass sometimes,” she says, “but I think his personality probably saved his life.”

In 2006, Drew cleared his credit that had been damaged by the identity theft and reached another key turning point, too: two years without a recurrence of his leukemia, a milestone, the doctors say, because the chances of recurrence drop radically after 24 months.

Today Drew walks with crutches (he is mostly in a wheelchair) and has joint pain related to his transplant. But he is carrying on with his life. He travels the country speaking about the benefits of cord blood transplants. He filed a lawsuit in December 2006 against the credit reporting agencies and several credit card companies, which resulted in a recent settlement with one agency that included concessions making it easier for patients to fight identity theft while they are hospitalized. He is also planning his wedding with Nicole, which will take place on the shores of Lake Tahoe this August. “It’s a fairy-tale ending that started out as a nightmare,” Nicole says. And, ultimately, Drew hopes, it’s a lesson that anyone who faces a life-threatening challenge can take to heart.

“It’s about personal accountability and taking responsibility,” he says. “We are not victims. We’re not being blown around like dust in the wind. We have control over our destiny.”