One June afternoon in 1992, a dancer named Matthew Sharp died eight times. A siren shrilled as he repeatedly dropped to the street and let strangers draw a chalk outline around his body. Then he stood up, took the chalk, and each time wrote the name of his partner, Johnny Franklin, inside the empty space—just like a cop at a crime scene.

Franklin had succumbed to AIDS in Oklahoma City two years earlier, and now Sharp was marching with the AIDS awareness group Act Up along Market Street in San Francisco’s annual gay pride parade. “Die-ins were a common form of AIDS activism in the 1980s and 1990s,” Sharp recalls. “They were conducted in complete silence every seven minutes while we were marching, because that was how often someone died of AIDS back then.”

After Franklin’s death, Sharp nearly became another victim when he came down with extrapulmonary tuberculosis. “I felt I was knocking on death’s door,” he says. “So I quit my ballet company, took the life insurance money Johnny left me, and moved to San Francisco, which was ground zero for HIV,” the AIDS virus. “For the next 20 years I stayed alive by participating in clinical trials of new drugs before they were released. I was aggressive about preventing opportunistic infections. When I began to die of wasting syndrome, I joined a trial for human growth hormone. I got an experimental thymus transplant. Combination therapy in 2008 finally brought my viral load down to undetectable.”

Still, there was the problem of Sharp’s T cells—the white blood cells, or lymphocytes, that unleash a powerful immune response against pathogens like HIV. For AIDS, the most critical of the T cells is CD4, which would normally coordinate the body’s attack against the disease. But by a quirk of biology, CD4 cells end up sequestering the virus, which ultimately decimates them. With Sharp’s CD4 cells hovering at around 250 per cubic millimeter of blood—a normal count is 500 to 1,500—he was prone to a host of opportunistic infections and qualified for a diagnosis of full-blown AIDS. “I was always in the danger zone, and every year I would come down with pneumonia,” Sharp says.

Then came an invitation to participate in a novel form of gene therapy, one that could mark a first step toward a true cure for AIDS. The trial was run by Jay Lalezari, director of Quest Clinical Research in San Francisco. Sharp agreed to join. His blood was drawn and his CD4 cells were filtered out, frozen, and transported to a laboratory where they were genetically altered to resist invasion by HIV. This was done by deleting a receptor on the surface of the CD4 cell that HIV uses to get inside. The reengineered CD4 cells were allowed to multiply in the lab and then returned to Lalezari.

In September 2010 Sharp received a single infusion of 20 billion of his genetically engineered immune cells. Within weeks his CD4 count doubled. “They test me every month and my CD4 count hasn’t fallen below 400. I haven’t had the usual bout of pneumonia since this treatment. I’d love to get a second infusion,” Sharp says. “I’m 55 years old and feeling better than ever, and now there’s a possibility I’ll actually see a full cure of HIV in my lifetime.”

Curing AIDS? Wiping out a pandemic that currently affects 33 million adults and 2.5 million children worldwide and infects 7,000 new people every day? In the 30 years since scientists identified HIV as the cause of AIDS, the virus has proved unbeatable—hiding in the very immune cells that would kill it; reflexively and rapidly mutating; mysteriously persisting in the gut, kidneys, liver, and brain; subverting every vaccine (the best one so far has given only 30 percent protection); and roaring back to life almost the moment drugs are stopped. It has been years since anyone dared whisper the word cure at all.

But they are daring again with growing confidence, buoyed by new insights and technologies to fight a foe that Jay Levy, codiscoverer of HIV, compares to a “biological Trojan horse” and Jay Lalezari calls “a cellular bioterrorist that kills your first responders first.” Tapping into medical advances from gene therapy to stem cells, researchers are launching powerful counterstrikes against the virus. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) will invest $70 million over the next five years to support three multi-institution research efforts aimed at finding a cure. And the independent International AIDS Society, known for its conferences, has assembled a working group of world experts to spearhead a global strategy for the cure.

The latest turn seems as remarkable as the one patients celebrated in 1996, when David Ho of Rockefeller University in New York presented his research on a combination drug therapy, a treatment cocktail that rendered the virus undetectable in blood. That work turned AIDS from a certain killer into a chronic disease almost overnight. “I remember witnessing a miracle,” recalls Steven Deeks, an expert in the pathogenesis of HIV at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “Literally within weeks, people went from a death sentence to a promise of years of health. People in hospices were sent home. And now there is a possibility we’ll have another dramatic shift.” He cautions, however, that it took “15 years to get from that first antiviral to truly effective, well-tolerated combination therapy. I think in terms of a total cure, we’re just now starting another 15-year journey.”

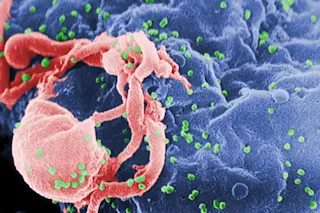

Renewed hope that we can defeat HIV is especially remarkable because of all we know about this outrageously complex and wily retrovirus—so called because it replicates by reversing the molecular process that most other viruses use. In most cases, viruses start with DNA as their primary genetic material and make RNA templates of themselves. Retroviruses, on the other hand, start with RNA and make DNA templates, using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase; the resulting DNA then exploits human cellular machinery to create more copies of the virus. HIV’s favorite target is the CD4 T cell, which orchestrates our entire immune response against the disease. The virus worms its way into the CD4 cell via several receptors—or molecular doorways—on the cell’s surface, including a crucial one called CCR5. Then it plunders that cell’s supply of reverse transcriptase. If the CD4 cell is quiescent, the HIV rests too. But if the CD4 cell is activated by anything, from stress to the common cold, the HIV inside becomes active as well, generating DNA templates that integrate into the human genome within the CD4 cell. Instead of killing HIV, as it would do with other viruses, the CD4 cell makes more copies of HIV, which then leave to invade other CD4 cells, ad infinitum, until an irreversible, lethal cascade has been unleashed.

The CD4 cycle alone would be enough to kill a person, but HIV also enters other cells, integrating into their genomes as well. The latent virus lurks, seemingly dormant but actually awaiting its cue: Anything that stirs the immune system—stress at work, food poisoning, grief—can jolt HIV combatants to action too. Some scientists suspect that this latent reservoir causes the long-term inflammation often experienced by people living with HIV, even when they are on the drug cocktail that otherwise controls the disease. Over the years, latent HIV might wreak silent havoc, making the need for a true cure all the more pressing as time goes on.

Recent studies clarify the limitations of Ho’s combination drug approach. A multicountry study published in The Lancet in 2008 found that someone starting HIV treatment at age 20 could expect to live to 49, a reduction of 27 years compared with those without the disease. Then there is what doctors call neuroAIDS. Even with antiretroviral treatment, between 40 and 60 percent of HIV-infected individuals develop mild neurological dysfunction; 1 to 5 percent develop dementia. A recent study suggests this syndrome results from the way HIV injures astrocytes, the most common type of cell in the brain. In people with AIDS, about 5 percent of astrocytes are infected; some scientists speculate that these cells, in turn, spew out toxins that ultimately kill uninfected astrocytes nearby.

Furthermore, today’s drug therapies are aimed specifically at the current strains of HIV, but the virus will probably mutate, as every virus eventually does. “We can’t be complacent,” says Jay Levy, now director of the Laboratory for Tumor and AIDS Virus Research at UCSF. “It’s an active, untreated epidemic in other parts of the world. It could change and come back to haunt us in a new form.”

In the accelerating search for a cure for AIDS, medical researchers are actively pursuing three broad approaches. The first approach is gene therapy, in which a patient’s cells are genetically engineered to be invulnerable to HIV; this naturally occurring resistance already exists in 1 percent of Caucasians worldwide. The second approach involves latency activators, molecules that lure the virus out of its hiding places and into the open, where the body’s immune cells and targeted drugs are able to find and destroy it once and for all. Finally, scientists are intensely studying the immune systems of a unique group of people known as elite suppressors, who remain healthy after HIV infection, controlling the virus for decades on end.

Impressive advances in the lab and in patient trials make all three strategies look promising, but in the end there might not be a single cure. As with today’s drug cocktail, the best solution might be a combination of two or perhaps all three. And even the concept of “cure” may need adjusting. Since it would be staggeringly difficult to test every single cell in the body for the presence of HIV, a patient will be considered cured if there is no evidence of the disease for a certain length of time after the completion of treatment. For millions of patients, that would be a life-transforming and life-affirming event.

Anyone lucky enough to resist infection with HIV altogether likely lacks the CCR5 receptor on the surface of his CD4 cells. The existence of this natural protective mutation was first reported in Nature in 1996. When Gero Hütter, today a specialist in blood cancers at the Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Immunology in Mannheim, Germany, read about it, he was transfixed. “I thought, wow, this could be a way to treat HIV.”

But conferring resistance on someone not born that way is a tall order. It requires redrawing the immune system by knocking out the existing cells and administering HIV- resistant stem cells that can establish a new immune system. Given the effectiveness of the drug cocktail, Hütter would not have considered such a risky procedure for AIDS alone. But if he were performing a stem cell transplant for a cancer patient who also happened to have AIDS, he reasoned, then why not use stem cells with the CCR5 deletion? “And then I forgot about it,” he says, “because I never saw a patient I could try it on—until Timothy Ray Brown showed up.”

Brown is the only person alive today who has been cured of HIV. He is, in the words of Gerhard Bauer, a stem cell researcher at the University of California, Davis, “the world’s first natural gene therapy experiment for HIV.” He came to Hütter—who was then at the Charité, a university hospital in Berlin—in 2006 with leukemia and an HIV infection that was well controlled with combination antiretroviral therapy. After cancer chemotherapy failed, Brown needed a stem cell transplant for his leukemia. The doctors’ plan was to kill off Brown’s cancer-producing bone marrow cells with intensive chemotherapy and replace them with stem cells from the bone marrow of a healthy donor. Hütter looked through multiple donor registries and tested the blood of more than 200 candidates for someone born with the CCR5 mutation. Luck was on Brown’s side: A matching donor had the deletion. Brown underwent his stem cell transplant and stopped taking his antiretroviral drugs. For 60 days afterward, there were still signs of viral DNA in his genome, but then it seemed to vanish. “The clearance of the HIV reservoir was quite rapid,” Hütter says, sounding as astonished in 2011 as he was back in 2007.

One year later Brown’s cancer returned, and he was given another stem cell transplant from the same donor. Today he is free of both cancer and HIV. Hütter speculates that Brown was helped to a total cure by what is known as the host- versus-graft reaction: New stem cells and all their progeny see the old immune cells as “other” and kill them off. When that happens, all the latent reservoirs of HIV that are permanently integrated into the genomes of those cells can be eliminated as well. Brown is now being studied in San Francisco by Jay Levy and his colleagues. “The fact that you can find a person who had AIDS and who now seems to have eradicated the virus is remarkable,” Levy says.

The treatment that cured Brown of his HIV and cancer has some devastating potential downsides, however. For one, transplanted donor cells can be rejected just like a donor heart, putting the patient at risk of disease and often requiring powerful immune suppressants, with all the attendant side effects and risks. With the current AIDS drug cocktail so effective, such dangers would be unacceptable unless, as with Brown, the patient needs bone marrow therapy anyway.

Building on Brown’s amazing recovery but hoping to avoid the pitfalls, AIDS researchers are devising treatments based on the patient’s own tissue, which would not be subject to rejection like donor cells. One of the most promising approaches uses a new type of genetic scissors known as zinc finger nucleases, developed by California-based Sangamo Biosciences. These finger-shaped proteins form when specific amino acids (protein building blocks) bind to a charged zinc atom. They can be engineered to go into cells and snip any gene a researcher wishes to target (including the gene for the T-cell receptor CCR5). The damaged cells automatically set about repairing the cut, yet 25 percent of the time that effort fails, and the deleted gene is never restored. Such cells can be separated out, creating a pool of HIV-resistant cells lacking CCR5. These lab-engineered cells can then be amplified and grown out a hundredfold or more before being infused back in. They are safer than cells transplanted from a donor because risk of rejection is gone.

The first human trials testing genetically engineered cells missing the CCR5 receptor, begun in 2009, have been small but impressive. At Quest Clinical Research, Lalezari enrolled nine men on the cocktail with persistently low CD4 counts who were HIV positive for 20 years or more. The genetically engineered cells survived after infusion, and CD4 counts went up in five of six patients he has reported on, including Matt Sharp. “The ratio of two types of immune cells, CD4 and CD8, which are often abnormally reversed in HIV, normalized, and the HIV-resistant cells even migrated to the gut mucosa, an important site for the virus,” Lalezari says. “The results were as good as I could possibly have hoped for.” Though his approach is distinctly different from a donor stem cell transplant like Timothy Brown’s—in which the entire immune system is replaced—it is a promising start, with potentially significant clinical benefit and far less risk.

A similar trial launched in 2009 by pathologist Carl June and internist Pablo Tebas at the University of Pennsylvania has shown equal promise. Here, six patients suspended combination antiretroviral therapy for 12 weeks after infusion with altered CD4 cells, so scientists could monitor viral load and the power of the altered immune cells to survive and thrive in the presence of active HIV. At present, two of the patients have been fully studied. In one patient, the virus took 10 weeks to rebound instead of the usual two to four weeks. In the other patient, the virus was still undetectable 12 weeks out. The next step is to increase the percentage of genetically engineered cells, either by increasing the amount of cells in the infusion, by giving more than one infusion, or by administering chemotherapy to lower the number of untreated CD4 cells in the body before infusion begins. Other researchers plan to try this approach on patients who recently received a diagnosis of HIV and are not yet on antiretroviral therapy. “It sounds like science fiction, I know, as if I just told you people landed here from Mars,” Tebas says. “That’s how far the technology has evolved.”

The most viable form of this treatment might be to target progenitor cells giving rise to CD4 cells and the rest of the immune system—stem cells themselves. If some of those cells could be removed from a person with AIDS, genetically engineered to be resistant, and then returned to the patient, they might spawn an immune system that is completely resistant to the disease. The virus could actually help, since it would continue infecting and killing unchanged, vulnerable cells—decimating its own resources in the process.

A stem cell transplant like this has already been accomplished in mice by virologist Paula Cannon of the University of Southern California. Cannon used a special strain of mouse that lacks a functioning immune system and so can be given human immune cells without rejecting them. Mice were infused with human stem cells, half of them genetically engineered so that the CCR5 receptor was gone. After 8 to 12 weeks, the modified cells had increased in number, effectively resisting infection with—and controlling replication of—HIV.

“These mice are a real breakthrough for HIV research,” Cannon says. “But now we need to find the sweet spot, the Goldilocks spot, where we can alter enough stem cells to allow someone to live with HIV.

Ultimately an anti-AIDS stem cell transplant might look like this: You would have your stem cells withdrawn and genetically altered to resist HIV. Simultaneously, you would get a mild form of chemotherapy to wipe out some of your remaining vulnerable stem cells. Then you would get an injection of the new stem cells. They would proliferate rapidly and create a resistant immune system. This immune system, especially the CD4 T cells, would have an advantage because HIV could never invade or kill them, and over time, they would become dominant.

Some researchers are optimistic that stem cell therapies might be able to deliver what researchers call a functional cure: Patients would achieve a state of remission in which the viral load was less than 50 copies of HIV per milliliter of blood, undetectable on standard tests, and they would no longer require medication. “This therapy isn’t about eliminating every last HIV from the body. It’s about giving the body the tools to stay well when the reservoir wakes up,” Cannon states. “If people can have this treatment, not have to take HIV drugs, not have detectable levels of the virus, and have a fully functioning, happy immune system, isn’t that good enough?”

Not for David Margolis, an AIDS researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. When the virus lurks in latent reservoirs in the body, he says, there are consequences for patients’ health. “You’re not going to cure HIV this way. It’s a giant technological problem as difficult as inventing a warp drive to travel to other stars. Unless you go in and kill all the stem cells that make CCR5, there will always be cells that the virus can grow in. You may lower the load, you may even prevent disease progression and eliminate need for antiretrovirals, but you will still have chronic immune activation and the problems caused by that.”

For the ultimate cure, doctors might have to purge HIV from its silent reservoirs, routing it out so it can never recrudesce and cause damage again. Margolis and collaborators hope to do just that through a “sterilizing cure” that spurs HIV to start replicating within its hiding spots; when the virus is actively dividing, antiretrovirals can get in and do their job.

Initial attempts to lure HIV out of hiding did not fare well. An early trial conducted in the mid-1990s in the Netherlands used inflammatory antibodies to fire up patients’ immune systems in hopes of activating the dormant CD4 cells where HIV was stowed away. The antibodies did in fact activate the CD4 cells but eventually killed them as well, depleting the body’s best weapon against HIV. “The early studies failed miserably and had toxic side effects,” says virologist Warner Greene of UCSF. “Ultimately we need to find molecules that activate the virus without activating the T cells or other viruses, and it’s not a trivial task.”

Some molecules are already showing promise. For example, an enzyme called histone deactylase (HDAC) keeps HIV turned off, a crucial part of the virus’s strategy of hiding in the T cells to avoid the body’s defenses. But in 2000, Margolis and his group discovered that they could use HDAC inhibitors—drugs already approved for stabilizing mood and preventing seizures—to reverse the effect and draw out the virus. First, the team tried a common and relatively weak HDAC inhibitor called valproic acid to bring latent HIV to life. “It was not the best drug, not the most specific or potent, but it was already in clinical use, and people were taking it every day,” says Margolis, who published his initial results in The Lancet in 2005. It worked to a degree, reducing latent HIV load without activating T cells in about half the patients, though even in that group the effect plateaued or weakened over time. He is now focusing on a far more potent HDAC inhibitor, a relatively untested drug called vorinostat that is currently used to treat a few rare types of cancer. Finally, an immune molecule called interleukin-7 seems to flush out viruses from CD4 cells. Studies have shown it is well tolerated in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy, and several clinical trials are under way.

The hitch: Perfecting this kind of treatment could require a complicated and possibly dangerous new drug cocktail. HDAC inhibitors may activate viruses other than HIV, unleashing a plague from within. AlteRNAtively, they could increase the risk of cancer by changing the way in which cells transmit genetic instructions from DNA to cellular proteins. “Whether these approaches will work alone or require additional combination therapies is a question that we hope to be able to answer in the next few years,” Margolis says. “This is not going to be a single-shot, zero-sum game.”

The puzzle pieces should come together once we understand a special group of patients called elite suppressors, the one-in-300 HIV-positive adults with turbocharged immune systems capable of hunting and killing HIV. Timothy Ray Brown and others missing the CCR5 receptor beat HIV because their cells do not allow the virus to get in. Elite suppressors stay healthy because they pummel the virus and hold it at bay.

In June 1992 Loreen Willenberg, then a 38-year-old landscape designer, dreamed that she had been infected with HIV. “I suspected my former fiancé of risky behavior, so I went to get tested,” she explains. That test was equivocal; with the dream still haunting her, she got tested again two weeks later. “This time I was positive,” she says.

That September Willenberg saw an HIV specialist and her CD4 count came back astoundingly high—over 1,800. “My doctor said, ‘Look, this is very extraordinary, let’s just keep tabs on you.’ After three years of undetectable viral load and a high CD4 count, he said, ‘Loreen, I think you’re a member of a special group that’s being studied at the NIH now. They get infected and stay infected, but they don’t get sick.’ ” Twenty years after getting diagnosed, Willenberg is still healthy and has participated in several long-term studies aimed at decoding why her body has been able to prevail over AIDS.

At first scientists speculated that patients like Willenberg were infected with a weaker version of HIV. Joel Blankson of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine found otherwise. “They have a fully pathogenic virus,” he says, citing his study of a monogamous married couple infected with the same strain of HIV. The husband, a former drug user, contracted the virus 20 years ago. Seven years later, the wife was diagnosed. “He’s on triple antiretroviral therapy, and she is an elite suppressor who never got sick.”

Only now are scientists beginning to understand the biochemistry that makes this possible. One factor: differences in surveillance proteins called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) embedded in our cells. These molecules function by shuttling broken-down proteins called peptides from inside the cell to the surface, where other immune cells inspect them to see whether they are invaders. HLAs come in hundreds of forms, but elite suppressors tend to have two specific types, HLA-B*27 and HLA-B*57. A study published last year by the Ragon Institute (formed to facilitate collaboration among vaccine researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard, and MIT) suggests that those antigens may help educate CD8 immune cells to make them more potent against HIV, as well as hepatitis C. All CD8 immune cells—like the CD4 cells that harbor HIV—mature in the thymus (an organ devoted to the production of T cells) before taking up active duty in the body; while there, HLAs expose the CD8 cells to a variety of peptides, both human and foreign. Some HLAs—particularly HLA-B*57—tend to bind to a much higher proportion of foreign particles; more HLA-B*57 means that the CD8 cells will be exposed to a broader range of foreign peptides, improving their ability to identify and terminate invaders, including, presumably, HIV.

Yet the unique HLA pattern doesn’t explain it all, according to Bruce Walker, one of the study’s authors. Walker’s colleagues tested the genes of 1,110 elite suppressors and 620 HIV-infected controls. They found that while elite suppressors often have the rare set of genes that code for HLA-B, those genes are “neither necessary nor sufficient” for controlling the virus. In other words, some elite suppressors lack the HLA-B genes and some non-suppressors have them. So the search goes on. Recently, for instance, the team found a group of elite suppressors with elevated levels of p21, a cancer-fighting protein that disrupts key aspects of the HIV life cycle in the lab.

While it’s too early to grasp all the factors involved, elite suppressors should help us finesse the cure and eradicate AIDS for good. Two decades ago, researchers imagined that a vaccine would end AIDS. Their approach proved unfeasible, but the goal is now in reach. “This has been an amazing year,” says Jeff Sheehy, communications director at the UCSF AIDS Research Institute and a board member of the AIDS Policy Project, also positive for HIV. “I came out about a year before the first AIDS cases were recorded. I had one brief, glorious moment before the world came crashing down, and this has defined my whole life. Now we’re talking about a cure.”

WHY SOME PEOPLE ARE IMPERVIOUS TO AIDS

Approximately 1 percent of Caucasians lack a protein called CCR5 on their CD4 T cells—the white blood cells that normally kill invaders but that harbor HIV. CCR5 is a molecular doorway that lets the virus in. Since HIV depends on CCR5 to slip inside the CD4 cells, people with the receptor are prone to develop AIDS. Those without the CCR5 portal generally do not take HIV into their CD4 cells and have natural resistance to AIDS. Gene therapy could impart this kind of resistance to others.

Drugs for the HIV-free

University of North Carolina immunologist Myron Cohen was amazed to hear thunderous cheers from the audience of scientists and clinicians at the sixth International AIDS Society Conference on HIV in Rome last July. He had just presented results of a landmark trial of 1,763 heterosexual couples from nine countries in which one partner was infected with HIV and the other was virus-free. Early use of antiretroviral therapy for HIV, Cohen found, slashed the risk of transmitting the virus by 96 percent. In other words, drugs now used to treat AIDS could also prevent its transmission, winding down the epidemic if enough people begin therapy early.

The study randomly assigned couples to one of two groups. In one, the infected partner began drug therapy immediately. In the other, infected partners deferred treatment until their CD4 T cells (the immune cells the virus targets) fell to a perilous count below 250, or until they suffered an AIDS-related illness. Couples in both groups received HIV primary care, counseling, and condoms. After announcing their preliminary findings, Cohen and his colleagues offered treatment to all of the study participants and will continue to monitor them to see how the effect holds up over time. They are also planning a second study on men who have sex with men.

In a related study conducted in Kenya and Uganda, University of Washington scientists reported a profound reduction of transmission when a noninfected partner was treated instead of the infected partner. Uninfected partners who took a drug called tenofovir had a 62 percent drop in HIV infection; those who took a combination of tenofovir and another drug, Truvada, saw a 73 percent decline. With the Centers for Disease Control developing guidelines that would allow an uninfected person to take Truvada, the era of AIDS prophylaxis is about to begin.

JILL NEIMARK is a science journalist and author. Her ’tween fantasy adventure novel,

The Secret Spiral, was published in July. She is a contributing editor at DISCOVER.