John Leavell bends down, catching a 50-pound, cast-iron manhole cover with a T-shaped hook and sliding it aside. He then attaches one end of a thin hose to a battery-powered pump and drops the other into the darkness below. “Yesterday we couldn’t retrieve any samples,” says Leavell, a contractor for the non-profit Current Water. “Everything just froze. It was not pleasant.”

The manhole, located outside the Baton Show Lounge in Chicago, is his second stop of the day. Once he and his team have pulled, labeled and double-bagged two 50-milliliter bottles of raw sewage here, they’ll head across town to sample another manhole — and then deliver their bounty to a microbial ecology lab. Rinse and repeat, four days a week.

It’s a ritual that’s taking place across the country. In September 2020, the CDC launched its National Wastewater Surveillance System to monitor for COVID-19 upsurges using clues that Americans flush away. It’s become the first widespread use of wastewater-based epidemiology since the technique was used to track polio in the mid-20th century, and already it’s filling critical gaps in clinical testing.

Read More: Why Scientists Don’t Want Our Poop to Go to Waste

“We know people infected with SARS-CoV-2 shed fragments of the virus in their stool, whether they have symptoms or not,” says microbiologist Amy Kirby, the program’s lead at the CDC. Wastewater monitoring thus detects infections from the entire population, including individuals who never seek out a test or who take an at-home test and neglect to report their results to a health department. And since the virus can be identified in stool from the onset of infection, potentially days before noticeable symptoms appear, wastewater can even predict future case trends.

From the Sewers to the Lab

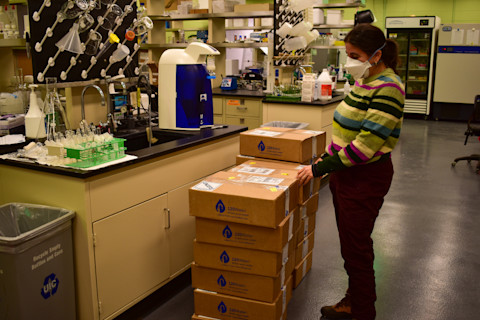

Rachel Poretsky, an associate professor of biological sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago, stands next to a chest-high pile of cardboard boxes in her lab. Each contains a sewage sample from downstate surrounded by ice packs and labeled with a QR code by 120 Water, a vendor that pivoted quickly from shipping Chicago Public Schools water samples for lead testing to wastewater during the pandemic. Also present are samples from treatment plants and those samples collected from city manholes by Current Water and engineering firm CDM Smith.

Microbial ecologist Rachel Poretsky stands next to a new delivery of wastewater samples. (Credit: Christian Elliott)

Christian Elliott

The past two years have been a whirlwind, says Poretsky — scaling up the lab to receive, organize, process and log data from hundreds of samples with less than a day’s turnaround is strenuous work. The wastewater-based epidemiology project, which she leads at the Discovery Partners Institute, is truly science at an unparalleled pace. “Usually when you start a new project you spend time refining your methods, doing various experiments and then settling on something,” Poretsky says — sometimes it takes decades. In this case, “everybody uses the analogy of building the plane while flying it.”

She and her colleagues load the samples into an instrument that concentrates pieces of the virus using magnetic beads in a few microliters of water and then extracts the viral RNA. But labs across the U.S. use a variety of methods as they try to scale up processing, including centrifuges and even skim milk to cause the virus to clump together. Clinical testing skips these steps because viral concentrations from nasal swabs are high enough to detect directly; wastewater, in contrast, is a “complex matrix” of microorganisms, organic material and SARS-CoV-2 fragments diluted in varying amounts of water.

Then comes the critical step: a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, or RT-PCR, which exponentially copies target RNA sequences to detectable levels. The Poretsky lab’s newest addition is a digital PCR machine that splits a sample into 26,000 partitions with one piece of RNA per partition, on a tray that looks like a giant cartridge in a high-tech printer. Unlike standard PCR machines that spit out a mere “yes” or “no” in terms of whether the virus is present, this one tells scientists how many copies of RNA were in the starting sample — or in other words, exactly how much virus was in the wastewater.

The Poretsky Lab's digital PCR machine. (Credit: Christian Elliott)

Christian Elliott

Poretsky then sends the analyzed samples to Argonne National Laboratory in suburban Chicago for sequencing. It’s the job of geneticist Sarah Owens to look for any mutations, like the 40 or so that commonly correspond to the omicron variant. “This is a pretty complex problem, to tease out these viral genomes that are very similar to each other to determine variants of concern,” she says.

It’s even more difficult to sequence the virus from millions of contributors in a sewage sample, rather than a single person’s nasal swab. For one, RNA can degrade in sewage. Sequencing viruses is a new challenge for Owens, who previously focused on DNA-based bacterial pathogens in samples from urban waterways. Still, she’s recently succeeded in disambiguating variants in samples and calculating the relative abundance of each. By the time the next COVID-19 variant of concern emerges, she says, she should be able to track its spread over time in wastewater across the state.

And Poretsky’s lab archives all the samples at -112 degrees Fahrenheit. That way, when a new variant inevitably does arrive in the U.S., she and Owens can return to the samples and sequencing data to learn exactly when it started showing up in the city. “I think a lot of people wish that existed when this all first started,” Poretsky says. “We could have gone back and said, ‘Hey, was this here in April 2020?’”

Frozen samples chill at -80 degrees Celsius in Poretsky's lab. (Credit: Christian Elliott)

Christian Elliott

From the Lab to Public Health Action

The final challenge is figuring out what the data mean and how to make them “actionable,” in the language of public health. That’s where Aaron Packman, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University, comes in. Using sewer line maps, his team can chase outbreaks backward from any manhole. “If you see a spike in SARS-CoV-2 RNA it’s possible to go further upstream and localize the source,” Packman says. “That’s something you can’t do with a wastewater treatment plant, but you can once you work within the sewer network.”

Some challenges remain. When it rains, for example, wastewater sometimes backs up into buildings or overflows into the nearby river and lake. During storms (made more frequent by climate change), the wastewater is diverted 300 feet underground and out of the city to a 6.5-billion-gallon reservoir. All of this means scientists must adjust for volume to avoid diluted samples skewing the data.

“It's hard to directly relate a wastewater measurement to an actual number of cases,” Packman says. “But we've accumulated a lot of data now and we can make better estimates of the total number of sick people using wastewater data plus clinical data than clinical data alone.”

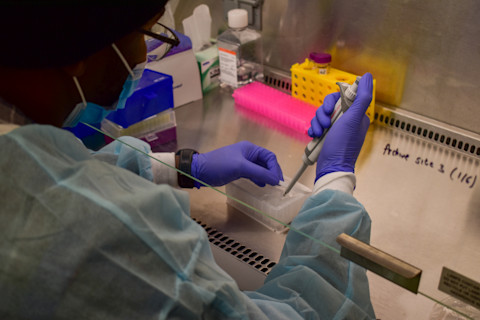

Modou Lamin Jarju, a lab technician in Poretsky's lab, pipettes samples. (Credit: Christian Elliott)

Christian Elliott

The Illinois Department of Public Health and Chicago Department of Public Health meet with the research team every other week to discuss trends in wastewater data and plan where to deploy more testing, vaccine clinics and extra hospital staff based on that data. “Everything with COVID is new, including wastewater surveillance,” says Isaac Ghinai, medical director of the CDPH. “And so, there's lots to understand about this data before it can be used exactly the same as case-based surveillance when there's a bit more of a track record.”

With the surveillance system finally scaled up and data pouring in, wastewater’s gone mainstream. Even if COVID-19 finally gives way, some public health departments hope to use sewage to keep an eye out for future unknown pathogens, monitor drug-resistant organisms in long-term care facilities, track influenza seasonally and even find hot spots for opioid usage.

“The infectious disease tracking system in this country was set up 50 years ago,” Packman says. “And it basically relied on people going to hospitals. But now it's absolutely clear that we will do a better job of identifying public health problems and responding to them if we combine the clinical and environmental surveillance information. That's the new frontier.”