An illustration of sperm and egg. (Credit: Liya Graphics/Shutterstock) A team of scientists has grown functional mouse sperm cells from cultures of embryonic stem cells. In principle, embryonic stem cells can become any type of cell in the human body, but convincing them to differentiate into what scientists want them to become can be a challenge. For years, researchers have tried to shape stem cells into working sperm in a dish – with limited success. Now, researchers from China say they’ve not only managed to grow functional, sperm-like cells from a culture of embryonic stem cells, but that those cells fertilized an egg and produced healthy, fertile offspring. They say it could be the first step toward better treatment for male infertility, as well as a better way to study the causes of infertility and even the origin of testicular cancer and some genetic mutations.

Where Sperm Come From

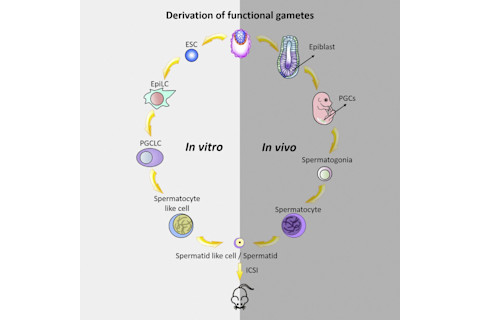

In the womb, a fertilized embryo forms an outer layer, called the epiblast, which is made up of embryonic stem cells – cellular blank slates with the potential to become any kind of cell in the body, depending on how they express different parts of the genome. Chemicals called cytokines, along with the physical environment, decide what these cells will become. By the second week of development, some of them become primordial germ cells – cells that will eventually become eggs or sperm. If the embryo is male, each primordial germ cell divides to produce two cells called spermatogonia. Then they wait. Years later, when puberty begins, hormones wake up the spermatogonia, and each one divides to form two cells called spermatozoa. So far, all of the cells, from stem cells to spermatozoa, divided by mitosis, a kind of cell division that creates two new cells, both identical to the original, with a 23 pairs of chromosomes.

This chart shows how Zhou and his team generated haploid male gametes, or sperm-like cells, from mouse embryonic stem cells that can produce viable and fertile offspring. (Credit: Zhou, Wang, and Yuan et al./Cell Stem Cell 2016) The spermatozoa do something different. They divide in a process called meiosis, which has two stages and ends with four cells called spermatids, each with different combinations of the original cell’s genetic material. Each cell only has 23 chromosomes, not 23 pairs. A spermatid has half the genetic information needed to create a new organism; when it combines with an egg, it creates a zygote with 23 pairs of chromosomes – one pair from the father, and one pair from the mother.

The Proof is in the Offspring

A few research teams have managed to coax cultures of embryonic stem cells through a similar process before, but Quan Zhou’s team is the first to produce sperm-like cells in a dish that could actually fertilize an egg to create healthy baby mice, which also grew up to produce another generation. They published their results in the journal Cell Stem Cell. One previous study did produce live offspring, but they had developmental abnormalities and couldn’t reproduce on their own. The difference, according to coauthor Xiaoyang Zhao, is that in those earlier studies, there was no way to be sure that the cells had split up their genetic material correctly during meiosis. This study was the first one in which researchers could prove that the cells had gone through each of the key stages of meiosis, and that each cell had the right number of chromosomes in the right places during the process. “We think the correct in vitro meiosis process made the offspring healthy and fertile in our study,” says Zhao.

Creating “Spermatid-Like Cells”

To get there, they started with embryonic stem cells from mice, then exposed them to a mixture of chemicals, called cytokines, that normally signal some epiblast cells to differentiate into primordial germ cells. In response, the cell cultures divided and differentiated into something that looked a lot like primordial germ cells. They combined the cell culture with a culture of testicular cells from mice which had been genetically engineered not to produce spermatocytes. The result, once researchers introduced a new mixture of cytokines and hormones like testosterone, was that the cells had an environment very similar to the testes of a mouse. In that environment, they underwent meiosis and produced. The researchers call the end result spermatid-like cells, instead of just sperm. Lab-grown cells hold the same kind of genetic material as normal sperm and they behave the same way, but they look a bit different — they don’t have tails. Therefore, sperm-like cells need to be injected into an egg in order to fertilize it. “There are still obvious differences between sperm-like cells and in vivo sperm, as sperm-like cells are not motile as in vivo sperm, and their shapes are different,” says Zhao.

More Research Ahead

The researchers hope to solve a major cause of male infertility, but it will be a while before they’re ready for human trials. The genetic expression necessary to create primordial germ cells in mice is slightly different from the human version. Researchers have more questions to answer before they can move forward. There are also some sticky ethical issues involved in work with human embryonic stem cells. Zhou and his colleagues expect their method to work with adult stem cells as well, but they still need to prove it in the lab. The team hasn’t yet set a timeframe for human trials, but they’re moving forward with their work. “We are trying to move to primate study and hope to get similar results,” says Zhao.